Vapor Barriers & Building Condensation

Vapor Barriers & Building Condensation

Part 2

- POST a QUESTION or COMMENT about the need for & role of vapor barriers beneath building wall siding

Vapor barrier & building condensation problem solutions:

This article discusses how to solve difficult vapor barrier location & indoor condensation problems.

In a series of questions and answers about vapor barrier location problems we explain when and why condensation occurs inside buildings, explains the problems caused by excessive indoor condensation.

We discuss how moisture enters building wall and ceiling cavities, and we summarize the best approaches to prevention of indoor moisture and condensation problems. Illustration at page top and accompanying text are reprinted/adapted/excerpted with permission from Solar Age Magazine - editor Steven Bliss.

InspectAPedia tolerates no conflicts of interest. We have no relationship with advertisers, products, or services discussed at this website.

- Daniel Friedman, Publisher/Editor/Author - See WHO ARE WE?

Vapor Barriers & Building Condensation - Solving Tricky Problems

"Vapor Barriers, Part II - Vapor Barriers and Condensation, building researchers are helping out with the tricky questions" - links to the original article in PDF form immediately below are followed by an expanded/updated online version of this article.

"Vapor Barriers, Part II - Vapor Barriers and Condensation, building researchers are helping out with the tricky questions" - links to the original article in PDF form immediately below are followed by an expanded/updated online version of this article.

Our photograph shows an insulation retrofit that jammed fiberglass between rafters over an attic, combined with a foil "radiant barrier" that in our view risked moisture traps or future roof leak traps (and building damage) hidden under the roof decking.

[Click to enlarge any image]

Along with tables summarizing building moisture research from the National Forest Products Laboratory, this article answers the following building condensation and materials questions:

- Do insulating sheathings on building walls cause condensation problems?

- Do insulating wall sheathings put the vapor barrier on the wrong side of the wall?

- How much lower can the ratio of inside to outside wall surface moisture permeability be without a problem on walls with exterior insulating sheathing?

- Is polystyrene insulation better than foil faced insulated sheathing for preventing condensation?

- Should vent strips be installed when using foil-faced building insulation on walls?

- How do stressed-skin panels affect building condensation problems?

- How much vapor transmission takes place through foam insulation?

- Is it safe to add retrofit building insulation without adding a vapor barrier?

- What conditions cause high indoor humidity and condensation?

- How can a crawl space be both insulated and ventilated?

- Why do we need to vent ceilings if walls do not need venting?

- How about insulation and vapor barriers for a full basement: where does the vapor barrier go?

- Where do we place the vapor barrier in raised floors of buildings constructed over open crawl spaces or on pilings?

At part I, VAPOR BARRIERS & CONDENSATION in buildings we looked at the fundamentals of moisture condensation in buildings: what causes condensation, how to control condensation, and whether we should worry about moisture condensation in buildings. We concluded that small amounts of moisture condensation can occur and do occur in wall cavities, but that structural damage rarely occurs because the walls dry out before temperatures are warm enough to support wood rotting fungi.

Still, risks of paint-peeing, corrosion of metals, hidden costly mold contamination, and degrading of insulation R-values do exist. A dry wall cavity is certainly preferable to a wet one.

And the most reliable way to achieve a dry wall is by installing a continuous vapor-retarding membrane such as 6-mil polyethylene plastic, paying a lot of attention to joints and penetrations. In fact, the penetrations are usually more important than the main surfaces, since air leaks generally transport a lot more moisture into a wall cavity than does vapor diffusion.

In this article we will examine questions frequently raised about how various materials and applications affect moisture condensation. Even if you have a good handle on the theory, applying it can be trick. Some building materials both insulate and block moisture vapor flow, confusing the issue. And in some applications, moisture vapor flows reverse seasonally, or spaces need both ventilation and sealing. It is enough to make a moisture vapor conscious contractor move to Phoenix (where presumably it is warm and dry enough that not much mold grows).

Question: How about insulating building exterior wall sheathings? Do they cause moisture problems?

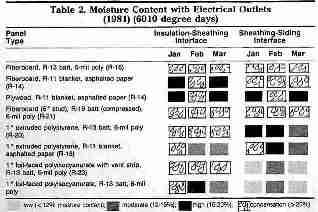

Answer: 1980's tests at the Forest Products Laboratory in Madison WI confirmed earlier reports that in a 2x4 wall in a moderately cold climate (7863 degree days), insulating sheathings caused no greater condensation hazard than ordinary sheathings. In fact, in the FPL tests, the insulating sheathings seemed to protect the siding from condensation, probably by slowing the flow of moisture to the siding.

For thicker insulated walls, which will have colder sheathing, or for buildings with more humid interiors (greater than 40 percent RH, which is most buildings with conditioned air in winter) these findings should be applied with caution. See Tables 1 (at the top of this page) and Table 2 (at left) that present some of the FPL findings.

Also see SIDING WOOD, FAILURES OVER FOAM BOARD where we describe wood siding failures when installed over foam insulating building sheathing, and see SHEATHING, FOIL FACED - VENTS - do we need to vent building walls with siding installed over foam board insulating sheathing?

Question: Don't insulating foam board wall sheathing products used on a building exterior put a vapor barrier on the wrong side of the wall?

Answer: A widely accepted rule of thumb holds that the building's exterior wall surface should be 5 to 10 times as moisture-permeable as the interior vapor retarder installed on the inside surface of the building's exterior walls. ("Retarder" not "barrier" is ASHRAE's preferred term). However, since insulating wall sheathings on a building exterior (under the siding) keep the wall cavity warmer and present a warmer face to the wall cavity, higher levels of vapor in the wall can be tolerated before condensation occurs. Hence the ratio of inside to outside permeability may be lower.

Question: How much lower can the ratio of inside to outside wall surface moisture permeability be without a problem on walls with exterior insulating sheathing?

Answer: You can play with the numbers if you're inclined, or hedge your bets by using a lapped and caulked poly vapor barrier with all wall penetrations sealed (our recommendation). This approach also controls air infiltration. Hence the awkward but useful phrase air/vapor barrier.

Question: Is polystyrene better than foil-faced foam insulating sheathing boards in preventing moisture condensation problems in building walls?

Answer: Theoretically, yes, because it is more permeable to water vapor; but no, because it has a lower R-value per inch. In the FPL tests,the foil-faced sheathing did slightly better, probably because the wall cavities were slightly warmer. Placing the rigid foam insulating board on the interior of the building wall side-steps the whole problem.

Question: How about using vent strips on exterior walls where foil faced building sheathing is to be installed?

Answer: These are probably not a good idea. Wall vent strips were tried on one wall in the FPL tests, and they actually increased the amount of wall cavity condensation. One possible reason is that the air drawn out of the wall through the vents was replaced with moist indoor air.

Vent strips were used only at the top of the walls. That wall venting design is similar to the problem of installing a ridge vent on a home with no soffit intake venting.

[The presence of the high vent and no source of outdoor air leads to the ridge vent acting as a "pump" to draw indoor air out of the building, increasing home heating costs, or in the case of the wall top exit vent, also increasing the movement of indoor moisture into the wall cavity - DJF.]

If wall vents are placed at both the top and bottom of the wall to solve this problem, the air movement through the wall cavity may degrade the R-value of the wall.

Our wall vent photo (above) shows a home-made wall vent installed by a building owner who hoped to avoid a moisture problem in the wall and in a raised wood floor over a concrete slab. At this building the ventilation system served only as an entry path for carpenter ants and water.

See SIDING WOOD, FAILURES OVER FOAM BOARD where we describe wood siding failures when installed over foam insulating building sheathing, and

see SHEATHING, FOIL FACED - VENTS - do we need to vent building walls with siding installed over foam board insulating sheathing?

Question: What about stress-skin insulated building panels and moisture problems?

Answer: Many stress skin building panels have no vapor retarder on the inside, just drywall, and low permeance sheathing, such as OSB or waferboard on the panel exterior surface. Theoretically, water could condense within the panel, most likely at the foam/sheathing board interface.

However, since on a 0 degF winter day, less than quarter of an ounce of water will diffuse through an entire 4x8 foot stress skin panel of foam (3 1/2 inches thick) over 24 hours, I wouldn't lose sleep over this. I have asked around, and have heard of only one problem with moisture (frost under the plywood facing of the insulated stress-skin building panel) and that was under near-arctic conditions.

I would be more concerned about caulking the stress skin building panel joints well so that moist air would not leak out and contact cold surfaces - not to mention lose heat. Nonetheless, a coat of vapor barrier paint wouldn't hurt.

Question: How do you determine the amount of vapor transmission through foam insulating board?

Answer: Moisture permeability ratings are like U-values. So if you can calculate heat transmission you can calculate vapor transmission. Perms measure the grains of water transported per hour per square foot per inch of mercury vapor pressure (the difference between the inside and outside moisture vapor pressures on the surface or material).

So, multiply the perm rating times the number of square feet of the wall, times the vapor pressure differences on the two sides of the wall, and you can count the grains of water.

Question: Is it safe to add retrofit insulation without also adding a vapor barrier?

Answer: If you add fibrous insulation to a cavity wall, it will increase the risk of a wall condensation problem and may exacerbate existing problems such as peeling paint. [Both Bliss and Friedman report having inspected buildings whose exterior paint was intact and sound until soon after insulation (without vapor barriers) was blown into previously empty wall cavities of homes in northern climates.-- DJF]

Nonetheless, various field studies in both moderate and cold climates have failed to find serious problems in the walls of retrofitted homes with or without vapor barriers. There are mitigating factors in older homes.

Of the ones that were monitored for relative humidity, few were much over 40 percent. Plus, most had highly permeable wood plank exterior wall sheathing, which tends to store and release any moisture condensate.

A reasonable approach would be to seal around moldings, electrical outlets, and other wall penetrations and keep building interior in the 40 percent range. When you redecorate, consider vapor barrier paint on the interior surface of exterior walls.

[In other words, we probably agree that where a newly-insulated older home has had a serious paint failure, there was most likely also a pre-exiting indoor high moisture level and indoor leaks or moisture problems, such as a wet basement or crawl area -- DJF.]

Two detailed articles discussing insulation retrofits, air leaks, moisture problems, and insulation effectiveness are

Question: What conditions create high indoor humidity?

Answer: In a very tight house, the normal moisture generated by human respiration and perspiration, along with cooking, bathing, and cleaning, can cause a moisture buildup. With additional moisture sources (building leaks, wet basements), high moisture levels can build up even in a not-so-tight building.

A frequent cause of high indoor moisture is the presence of a dirt floor crawl space, even if there is no obvious crawl space flooding. A water table three feet below the soil surface of a dirt floor basement or crawl space can release 12 gallons of water vapor per 1000 square feet in one day.

Covering the soil with a heavy polyethylene plastic cover should reduce this moisture movement into the home by about 80 percent and reduce crawlspace ventilation requirements by a factor of 10.

See these crawl space ventilation and dry-out articles:

CRAWL SPACE DRYOUT - home

Other building moisture sources are un-vented clothes dryers and combustion appliances, drying firewood indoors, and house plants.

See MOISTURE CONTROL in BUILDINGS for an extensive list of diagnostic and "how-to" articles on controlling moisture in buildings.

Also see HUMIDITY LEVEL TARGET.

Question: How can I both insulate and ventilate a crawl space?

Answer: one option is to insulate the floor above the crawl area with a vapor barrier on the warm side of the insulation (over the joists) and to leave the crawl space vented in all but the coldest weather, perhaps using thermally operated foundation vents (1980's convention).

Low permeance rigid foam board insulation is the best product to use here because it will also resist forming a problem reservoir of toxic but hidden mold.

(See Mold in Fiberglass Insulation).

Current (2009) best construction practices no longer ventilate crawl spaces; rather we convert the crawl space to an insulated, "conditioned" space, making sure that we keep out rot and mold causing water.

That's because experience and field studies indicate that it is just about impossible to control crawl space ventilation to work optimally for all weather and building conditions. -- DJF

Our photo (above left) shows a poly moisture barrier placed over dirt in a crawl space - also notice that radiator in the right of the photo - the owner converted this crawl to a dry, heated space - what may be missing is foundation perimeter insulation, perhaps using foam board, unless that step was already taken outside.

See the crawl space mold, ventilation and dry-out articles beginning at CRAWL SPACE DRYOUT - home

Question: Why do I have to ventilate an attic or cathedral ceiling if I don't have to ventilate the building wall?

Answer: No vapor-retarding system is perfect. And due to the stack effect (air movement upwards in buildings as warm air rises), a disproportionate amount of moist air will find its way into the ceiling cavity or attic space. Also, attic and roof ventilation help for summer cooling, ice dam prevention, and a cooler attic means a cooler roof deck which means longer roof life.

See ROOF VENTILATION NEEDED? and also

see ROOF ICE DAM LEAKS for more details.

Question: How about insulation and vapor barriers for a full basement: where does the vapor barrier go?

Answer: My opinion is that the basement wall should be treated much like the rest of the building shell - waterproofed on the outside (or more important, keep surface runoff and roof spillage away from the building foundation), and vapor-proofed on the inside (if you are finishing the basement interior walls).

Exterior foundation insulation will help keep the foundation wall warmer and less likely to condense water in winter and summer. By the way, if you've got standing water or even occasional wet floors in the basement, vapor barrier placement is a moot point - you need to solve the water problem first.

See WATER ENTRY in BUILDINGS, and the detailed articles that appear under that category.

Question: Where do we place the vapor barrier in raised floors such as buildings constructed over open crawl spaces or on pilings?

I am designing a pile supported wood building building and would like to know where to place the vapor barrier. Was thinking about placing is below the wood sheathing above the TJI , however this would not allow for the wood sheathing could not be glued to the TJI.

The under side of the TJI will be sheathed and could used bagged insulation however am concerned about the vapor getting stuck between the floor sheathing and sheathing attached to the underside of the TJI. The building is to be constructed in dead horse alaska and temperatures out door could be -50 degrees +-.

Do you have any recommendations on placement of vapor barrier in the floor system. Is it needed? Thanks for your time Chad

Answer:

Our photo (left) shows an older building in northern Maine. The structure, built on pilings, is exposed to both cold weather and high humidity from the Maine coast and waters from the Bay of Fundi, though it is not exposed to temperatures as cold as those in the question above.- Ed.

1) Exterior plywood sheathing

is a moderately effective vapor retarder with a perm rating of less than 1.0 as long is it is kept dry and the relative humidity is low. When plywood is wet or relative humidity is high, its permeance will range from above 1 to as high as 10.

This is because wood is a “hygroscopic” material that readily absorbs and releases humidity.

If you are using T&G plywood subflooring, you will have an effective vapor retarder (and an air barrier, as well, if you caulk the joints with a long-lasting sealant such as urethane or silicone) without the use of plastic sheeting.

If you are required by code to use a separate vapor retarder, you could place it in strips between the TJIs under the floor sheathing to allow proper gluing of the subfloor.

To avoid trapping water against the plastic sheeting from spills, plumbing leaks, or other sources, I’d suggest using felt paper rather than plastic. Like plywood, felt paper can absorb and release moisture and its permeance rises when wet, allowing drying to take place.2) Most moisture movement is from air leakage, not vapor transmission through materials,

so vapor retarders are less of an issue than once thought. In a cold climate, air and moisture are generally moving upward so movement of moisture down into the floor structure should be minimal.3) To be on the safe side,

I’d recommend using a vapor permeable material on the underside of your floor. Possibilities are fiberboard products or expanded polystyrene (or housewrap if you do not need a solid material).4) Local requirements:

We in the lower 48 are not used to -50 degree temps, so I suggest talking to local building experts about special details and code requirements for your area.References:

- Cold Climate Housing Research Center: Think vapor barrier when going post and pad

http://sustainable.cchrc-research.org/2010/07/think-vapor-barrier-when-going-post-and-pad/#more-1352- APA-The Engineered Wood Association

http://www.performancepanels.com/single.cfm?content=app_pp_atr_perm&

CFID=37546166&CFTOKEN=69915881- Research at the National Institute of Science and Technology has shown that the water vapor permeance is very sensitive to the relative humidity gradients. For example, at 50% humidity the water vapor permeance of plywood is approximately 1 perm but the water vapor permeance may be increased by a factor of 10 when the humidity is increased to 90%. Similar results are reported for an OSB siding product which had been coated with a latex paint.

- PIER or PILE FOUNDATIONS - construction & inspection for defects

Steven Bliss, Building Consultant, Burlington, VT

Here we include solar energy, solar heating, solar hot water, and related building energy efficiency improvement articles reprinted/adapted/excerpted with permission from Solar Age Magazine - editor Steven Bliss.

This article series about building vapor barriers and condensation in buildings series begins at part I, VAPOR BARRIERS & CONDENSATION in buildings, (when and why condensation occurs inside buildings), explains the problems caused by excessive indoor condensation, explains how moisture enters building wall and ceiling cavities, and summarizes the best approaches to prevention of indoor moisture and condensation problems).

Part II at VAPOR CONDENSATION & BUILDING SHEATHING (detailed questions and answers about various building wall sheathing and insulating materials and their impact on building condensation problems) is followed by VAPOR BARRIERS & AIR SEALING at BAND JOISTS. Readers should also see VAPOR BARRIERS & HOUSEWRAP.

Original article

- Vapor Barriers & Building Condensation Explained, Part 2 - PDF form, use your browser's back button to return to this page

- Vapor Barriers & Building Condensation Explained, Part 2 - PDF form, continued

...

Reader Comments, Questions & Answers About The Article Above

Below you will find questions and answers previously posted on this page at its page bottom reader comment box.

Reader Q&A - also see RECOMMENDED ARTICLES & FAQs

Question: where do I install the poly vapor barrier during insulation renovation or insulation retrofit?

Just happened upon this site and was pleased to find such great information on so many important topics. I was not able though, to find the answer to my questions about installing a vapor barrier of plastic sheeting when using unfaced mineral wool insulation in ceiling/attics and floors.

I have seen recommendations for using 6 mil plastic as a vapor barrier, but should it be installed between joists from above in attics and from below for floors. Or, when the ceiling and floors have been torn out, should the plastic be installed over the joists from the interior side? Thank you for any guidance you can give. - S.Z. 12/12/2013

Reply:

Generally:

- you want the plastic barrier always to be on the warm side of a floor or wall unless your home is in the hot humid south where the dominant HVAC-on mode is air conditioning.

- I prefer 6-mil poly over the cheaper 4-mil because I find that the plastic is not made to lab grade specs anyway and varies in thickness; sometimes some segments of 4 mil poly tears or is just too fragile for my taste;

- If you are retrofitting insulation in an attic it's a bit messy to wave the poly up and down over the ceiling joists (attic floor joists) from the attic side, but that would be far better than putting it atop the ceiling joists (that is on the cold attic side) as when you put the vapor barrier on the wrong side you risk trapping moisture in the building cavity, losing insulating value and even inviting mold growth;

If your renovation included new ceilings below you would put the poly on the underside of the ceiling joists, then install new drywall over that;

As we've learned in recent decades that by far the most air and moisture movement and leakage appear at the building ceiling or wall penetrations, those really are even more important than having a poly barrier at all; that is to say in some renovation situations where we are leaving old insulation in an attic floor but adding more atop the old, and where the ceiling is finished below, we skip the poly step but take care to seal every ceiling penetration (similarly with walls). In that case we might also use a vapor barrier paint on the interior side of ceilings and walls.

Finally, do not make a poly sandwich with insulation beween - like the hotel california, the moisture can check in but it can never leave (almost never) at least not before causing trouble.

Question: Should the cavity between the outer lining and vapour barrier simply be ventilated to allow the consensation to dry out or should measures be put in place todirect the moisture to the outside of the lining?

(May 7, 2012) Jason R said:

I am reviewing a building application to refurbish a large indoor pool complex which has been affected by condensation forming within the roof cavity. This has caused damage to interior linings and structural elements.

The architects plans are to replace the roofing and linings, checking the structural elements as they proceed, allowing the elements to dry out and treat where necessary.

An XPS polystyrene underlay to the original roofing which was saturated with moisture (and was probably where condensation was occuring) will be replaced with cavity insulation and a lining with vapour over to the underside of the roof structure.

A secondary lining will be placed over the vapour barrier supported on battens aor spacers.

Some of the ceiling lining will be a perforated metal sheeting with an acoustic layer behind to try to help control excess nosie in the spaces below. A vapour barrier will be applied to the wall in a similar way with a secondary lining spaced off the vapour barrier.

My concern is that while the vapour barrier should provide the control of condensation from getting to the structural elements, there is a possibility of a lot of condensation occurring behind the outer lining. given that it is a heated pool complex and the humidity is likely to be quite high for the most part i am concerned that a build up of vapour in the space will cause a premature deterioration of the lining (again) over a wide area of the linings.

Is there anything that should be done to help prevent this from occurring, or can you suggest a better construction technique?

Should the cavity between the outer lining and vapour barrier simply be ventilated to allow the consensation to dry out or should measures be put in place todirect the moisture to the outside of the lining?

Also with the inclusion of the cavity insulation between the vapour barrier and roofing is there a possibility of condensation also occurring at a secondary position inside the cavity which may cause similar damage that was first encountered?

Reply:

Jason, while I understand the appeal of "insurance" attributed to a second vapour barrier, I agree that double barriers, particularly with an air space between, invites trapped moisture that ultimately accumulates until it finds a pathway out as a leak. I'd prefer to use a single heavier mil poly barrier - 6 mil or better - or if doubling them, double without an air space between.

Pay most particular attention to all of the penetrations in the barrier as those are where the trouble will begin.

Question: tracking down moisture problems and stains vs sheathing and vapor barrier details

(Sept 13, 2014) Lowell G said:

I am currently building a 1000s.ft. house in Zone 5b/6 upstate NY and plan to use the following for the exterior wall construction: 5/8" drywall, 2x6 cavity filled(5") 2 lb. closed-cell polyurethane, OSB, house wrap and 3/4" continuous rigid insulation.

Do you think the choice of material of the 3/4" board as it relates to perm is critical to future potential moisture/mold problems somewhere along the traverse of the wall?

That is to say, would you choose 3/4" XPS or would you choose 3/4" rigid fiberglass allowing for the R=1 difference between them.?

Or does it even make a difference? Thank you.

(Oct 5, 2014) Priscilla said:

Is mold on plywood wall sheathing in attic area an indication of moisture build-up between the siding and the wall sheathing. And if so, what is the fix?

Reply:

Priscilla

You raise an interesting question but needing some clarification. "wall sheathing" in an attic? Do you mean roof sheathing? If so, it's common for condensation on the underside of a roof to produce mold stains - the mold genera/species usually found there range from harmless cosmetic to allergenic (usually species of Cladosporium) to occasionally more troublesome (Aspergillus sp.)

Moisture or moisture stains in that location can come from any moisture source, even the building basement or a crawl area.

But moisture build-up between siding and wall sheathing is not what I'd usually expect to show up in an attic unless there were an attic knee wall that were leaking into that space.

Housewrap is installed on sheathing before siding is installed specifically to keep water from entering the wall cavity and to allow moisture molecules to escape.

Question: cavity wall built wrong -[ concrete, brick, no vapor barrier

(May 8, 2015) omar said:

i have a big problem

my cavity wall is done wrong by applying it invertly

the exteror finish is a conrete wall the inside is a brick concrete wall

how can i insulate such a problem

the concrete wall is already build

i have to apply vapor barrier and polyiso then the brick wall from the inside

any solutions?

will this system work ?

Reply:

Omar

If there is a space between the walls and you can pump in closed cell insulating foam that will also act as a vapor barrier.

...

Continue reading at VAPOR BARRIERS & AIR SEALING at BAND JOISTS or select a topic from the closely-related articles below, or see the complete ARTICLE INDEX.

Or see these

House Wrap, Air & Water Barrier Articles

- AIR LEAK MINIMIZATION

- BASEMENT CEILING VAPOR BARRIER

- BLOWER DOORS & AIR INFILTRATION

- CRAWL SPACE VAPOR BARRIER LOCATION

- DRY-IN, DEFINITION

- FELT 15# ROOFING, as HOUSEWRAP/VAPOR BARRIER

- HOUSEWRAP AIR & VAPOR BARRIERS

- HOUSEWRAP INSTALLATION

- HOUSEWRAP PRODUCT CHOICES

- HOUSEWRAP at SILLS, SOLES, TOP PLATES

- INDOOR AIR QUALITY & HOUSE TIGHTNESS

- MOISTURE in BUILDING WALLS, EFFECTS

- PERM RATINGS of BUILDING MATERIALS

- PLASTIC MOISTURE BARRIER FLAME SPREAD

- RAIN SCREEN PRINCIPLES

- STUCCO WALL WEEP SCREED DRAINAGE

- VAPOR BARRIERS & AIR SEALING at BAND JOISTS

- VAPOR BARRIERS & CONDENSATION

- VAPOR BARRIERS & HOUSEWRAP

- VAPOR BARRIERS, VINYL SIDING

- VAPOR CONDENSATION & BUILDING SHEATHING.

- WATER BARRIERS, EXTERIOR BUILDING

Suggested citation for this web page

VAPOR CONDENSATION & BUILDING SHEATHING at InspectApedia.com - online encyclopedia of building & environmental inspection, testing, diagnosis, repair, & problem prevention advice.

Or see this

INDEX to RELATED ARTICLES: ARTICLE INDEX to BUILDING MOISTURE

Or use the SEARCH BOX found below to Ask a Question or Search InspectApedia

Ask a Question or Search InspectApedia

Try the search box just below, or if you prefer, post a question or comment in the Comments box below and we will respond promptly.

Search the InspectApedia website

Note: appearance of your Comment below may be delayed: if your comment contains an image, photograph, web link, or text that looks to the software as if it might be a web link, your posting will appear after it has been approved by a moderator. Apologies for the delay.

Only one image can be added per comment but you can post as many comments, and therefore images, as you like.

You will not receive a notification when a response to your question has been posted.

Please bookmark this page to make it easy for you to check back for our response.

IF above you see "Comment Form is loading comments..." then COMMENT BOX - countable.ca / bawkbox.com IS NOT WORKING.

In any case you are welcome to send an email directly to us at InspectApedia.com at editor@inspectApedia.com

We'll reply to you directly. Please help us help you by noting, in your email, the URL of the InspectApedia page where you wanted to comment.

Citations & References

In addition to any citations in the article above, a full list is available on request.

- Solar Age Magazine was the official publication of the American Solar Energy Society. The contemporary solar energy magazine associated with the Society is Solar Today. "Established in 1954, the nonprofit American Solar Energy Society (ASES) is the nation's leading association of solar professionals & advocates. Our mission is to inspire an era of energy innovation and speed the transition to a sustainable energy economy. We advance education, research and policy. Leading for more than 50 years. ASES leads national efforts to increase the use of solar energy, energy efficiency and other sustainable technologies in the U.S. We publish the award-winning SOLAR TODAY magazine, organize and present the ASES National Solar Conference and lead the ASES National Solar Tour – the largest grassroots solar event in the world."

- Steve Bliss's Building Advisor at buildingadvisor.com helps homeowners & contractors plan & complete successful building & remodeling projects: buying land, site work, building design, cost estimating, materials & components, & project management through complete construction. Email: info@buildingadvisor.com

Steven Bliss served as editorial director and co-publisher of The Journal of Light Construction for 16 years and previously as building technology editor for Progressive Builder and Solar Age magazines. He worked in the building trades as a carpenter and design/build contractor for more than ten years and holds a masters degree from the Harvard Graduate School of Education. Excerpts from his recent book, Best Practices Guide to Residential Construction, Wiley (November 18, 2005) ISBN-10: 0471648361, ISBN-13: 978-0471648369, appear throughout this website, with permission and courtesy of Wiley & Sons. Best Practices Guide is available from the publisher, J. Wiley & Sons, and also at Amazon.com - ASHRAE resource on dew point and wall condensation - see the ASHRAE Fundamentals Handbook, available in many libraries.

- 2005 ASHRAE Handbook : Fundamentals: Inch-Pound Edition (2005 ASHRAE HANDBOOK : Fundamentals : I-P Edition) (Hardcover), Thomas H. Kuehn (Contributor), R. J. Couvillion (Contributor), John W. Coleman (Contributor), Narasipur Suryanarayana (Contributor), Zahid Ayub (Contributor), Robert Parsons (Author), ISBN-10: 1931862702 or ISBN-13: 978-1931862707

- 2004 ASHRAE Handbook : Heating, Ventilating, and Air-Conditioning: Systems and Equipment : Inch-Pound Edition (2004 ASHRAE Handbook : HVAC Systems and Equipment : I-P Edition) (Hardcover)

by American Society of Heating, ISBN-10: 1931862478 or ISBN-13: 978-1931862479

- 1996 Ashrae Handbook Heating, Ventilating, and Air-Conditioning Systems and Equipment: Inch-Pound Edition (Hardcover), ISBN-10: 1883413346 or ISBN-13: 978-1883413347 ,

- Principles of Heating, Ventilating, And Air Conditioning: A textbook with Design Data Based on 2005 AShrae Handbook - Fundamentals (Hardcover), Harry J., Jr. Sauer (Author), Ronald H. Howell, ISBN-10: 1931862923 or ISBN-13: 978-1931862929

- 1993 ASHRAE Handbook Fundamentals (Hardcover), ISBN-10: 0910110964 or ISBN-13: 978-0910110969

- The National Institute of Standards and Technology, NIST (nee National Bureau of Standards NBS) is a US government agency - see www.nist.gov

- "A Parametric Study of Wall Moisture Contents Using a Revised Variable Indoor Relative Humidity Version of the "Moist" Transient Heat and Moisture Transfer Model [copy on file as/interiors/MOIST_Model_NIST_b95074.pdf ] - ", George Tsongas, Doug Burch, Carolyn Roos, Malcom Cunningham; this paper describes software and the prediction of wall moisture contents. - PDF Document from NIST

- US DOE, RADIANT HEATING SYSTEMS, U.S. Department of Energy

- Best Practices Guide to Residential Construction, Wiley (November 18, 2005) ISBN-10: 0471648361, ISBN-13: 978-0471648369, appear throughout this website, with permission and courtesy of Wiley & Sons. Best Practices Guide is available from the publisher, J. Wiley & Sons, and also at Amazon.com.

- In addition to citations & references found in this article, see the research citations given at the end of the related articles found at our suggested

CONTINUE READING or RECOMMENDED ARTICLES.

- Carson, Dunlop & Associates Ltd., 120 Carlton Street Suite 407, Toronto ON M5A 4K2. Tel: (416) 964-9415 1-800-268-7070 Email: info@carsondunlop.com. Alan Carson is a past president of ASHI, the American Society of Home Inspectors.

Thanks to Alan Carson and Bob Dunlop, for permission for InspectAPedia to use text excerpts from The HOME REFERENCE BOOK - the Encyclopedia of Homes and to use illustrations from The ILLUSTRATED HOME .

Carson Dunlop Associates provides extensive home inspection education and report writing material. In gratitude we provide links to tsome Carson Dunlop Associates products and services.