How Adze, Axe, or Saw Cut Marks on Lumber Indicate Building Age & Wood Cutting Methods

How Adze, Axe, or Saw Cut Marks on Lumber Indicate Building Age & Wood Cutting Methods

Saw or tool marks can give both type of lumber or beam cutting and its age

- POST a QUESTION or COMMENT about how to read & interpret adze or saw cut marks on boards, framing lumber, & beams in old buildings

This article describes and illustrates different types of marks found on old wood boards and beams:

adze and axe marks, hand sawn lumber, mechanical pit-sawn lumber, circular saw cut marks, and modern planed or sanded smooth dimensional lumber.

We include a table of modern dimensional lumber nominal and actual sizes for kiln dried and treated wood.

We include research citations assisting in understanding the history and development of the mechanically-operated reciprocating saw or a mechanical and often portable replacement for the hand-operated "pit saw".

Photo at page top: pit saw kerf marks on a pit-sawn beam in a home in Cold Spring New York.

InspectAPedia tolerates no conflicts of interest. We have no relationship with advertisers, products, or services discussed at this website.

- Daniel Friedman, Publisher/Editor/Author - See WHO ARE WE?

Adze Cuts & Saw Kerf Marks Indicate Building Age

Generations of types of adzes, axes, broadaxes and saws used in cutting beams, and similar

details are readily available on many buildings.

Generations of types of adzes, axes, broadaxes and saws used in cutting beams, and similar

details are readily available on many buildings.

The marks left by these tools offer both clues to building age and wonderful aesthetic detail.

Below, in rough chronological order, we illustrate different types of saw and tool cut marks in wood: adze cuts, hand sawn pit saw marks, mechanically-operated pit saw marks, circular saw marks, and unmarked, planed modern dimensional lumber.

We discuss the visual comparison of adze marks, axe marks, hand sawn lumber, mechanical pit sawn lumber, and circular saw mill cut lumber and boards.

We include a table of dimensional lumber nominal vs. actual sizes.

Photo: post and beam construction of a barn in New York's Hudson Valley.

Timber frame construction initially used hand hewn beams, cut roughly rectangular by an adze and axe.

Later timber frame construction used sawn beams and still later wood frame construction used sawn sills, studs, joists and rafters.

Photo at page top: pit saw kerf marks on a sawn beam in a home in Cold Spring New York.

Article Contents

- AXE ADZ HEWN BEAMS & PLANKS

- SCRIBE & SQUARE RULE MARKS on TIMBERS

- SAW KERF MARKS on TIMBERS & BEAMS

- RECIPROCATING SAW HISTORY

- CIRCULAR SAW HISTORY

- DIMENSIONAL LUMBER

- DIMENSIONAL LUMBER SIZES

Adze, Axe, Broadaxe or Broad Hatchet cut marks in wood - hand hewn beams and planks

Commonly first timbers used to support structures such as roofs or later floors were used as round logs, sometimes with bark-on.

Commonly first timbers used to support structures such as roofs or later floors were used as round logs, sometimes with bark-on.

Our photograph just above shows the scoring axe cuts and hewing adze cuts that are normally visible in the rough surface of hand hewn wood structural beams.

The tool marks on the antique beam shown in this photo were most likely made using an adze or a combination of a broad-axe and adze.

The flattening was not done with an axe alone, as we can see the smooth surface left by the adze on some of the beam's surfaces.

When builders opted to finish beams beyond simply using a tree or log as a structural member, intial cutting timbers was done with an axe and then rough-hewn timbers were often further prepared with a broadaxe.

The broadaxe was used for hewing timbers (cutting down trees), a broad hatchet was used for hewing smaller timbers, and "The Carpenter's Adze-used to finish levelling the surfaces of sleepers and other floor pieces." Lehman (2015)

Often the builder would flatten just one or side of the round log in order to permit building a wood floor or roof.

Other timbers were hewn flat on just two sides, such as in the Missouri-French houses.

Most four-sided squared timbers we'll see in older buildings in Europe, the U.K., Russia, and in North America in standing buildings were flattened using an adze or a combination of adze and axe in which the axe made straight-on cuts into the log and the adz chopped out those chips and further flattened the surface.

The adze, a more specialized tool was thus used to roughly square-up wood framing membrers. But Interestingly, the adze is hardly a modern tool; it dates from pre-historic times when people made an adze out of chert or other stone.

Hand hewn beams, chopped and then sized with an adze and axe were used in North America from the 1600's into the late 1800's.

Adze marks on hand-hewn beams indicate hand hewn beams

An understanding of how hand-hewn beams were cut, for example, can permit the careful observer to not only recognize the type and age of building framing, but even to understand just where the worker was standing when a blow from a tool was delivered to a building framing member.

Hewing a rectangular beam out of a round log was done in two steps:

Scoring Cuts into the Log

Using an axe, broad-axe, or broad-hatchet, or possibly only an adze, a hoe-like cutting tool with wooden offset handle, the worker would make make a series of cuts along the round up-facing surface of a log.

For those who had one, a chalk line was used to mark a straight line along one or two sides of the log to guide the cutting, and the scoring cuts would be made to about the depth of the line. With a chalk line or more likely working just by eye, the worker most often used a broad-axe or a broad hatchet to make the cuts into the log surface.

Rough scoring cuts may have been as far as two feet apart along the log surface, and were not made to the full depth of the string line or sight line that represented the desired flat surface of the finished beam. Between these scoring cuts the wood would be chipped out by prying with the edge of the scoring axe or hatchet.

Additional scoring cuts closer to the final cut-line might be made using the broadaxe or broad hatchet or possibly the adze itself, followed by additional chipping.

Hewing Cuts Flatten the Log Surface: broadaxe vs. adze marks

In a final series of cuts, the sharp adze or more often an axe, broad axe or broad hatchet was used to cut away the curled "chip" of rounded log surface cut and then the surface was "planed" by the adze.

The axe cut was made at the base of the chip of wood cut and lifted by the adze. In our photo of a hewn beam above, the vertical cuts across the height of the log face (red arrow) are the cuts that were made to remove the chip, while the scalloped (green arrow) or split (orange arrow) rectangular face cuts are the marks left either by the adze blade or by the splits in the wood surface when the adze-cut chip was removed.

You can see by the fact that some of the cut surfaces are smooth that the hewing cuts were made by an adze.

A skilled worker might use a sharp broadaxe to cut on-the-flat along the log surface to flatten it to its final face when no adze were at hand; in that case we might see smooth but more rounded-scalloped cuts, or cuts that were angled into the wood and thus less-flat along the beam surface (as the axe blade could not be swung absolutely parallel to the beam face) where the blade of the axe or hatchet flattened the beam surface to the final cut-line.

More often in Colonial America the final beam facing was performed using an adze to smooth the surface. Had the chips just been split out of the you'd not see such flat, smooth cuts parallel to the beam face on the log face as are left by the adze.

This detail offers a very personal connection to the age of a building and to its past construction. You can actually place yourself where the worker stood to swing the tool.

Scribe rule vs. Square Rule Marks on Timbers

When pairs of individual timers are joined to one another with custom-fitting cuts to match their individual irregularities, most likely the European scribe rule procedure was being followed.

All of the timbers were pre-assembled on the ground, scribed using a metal awl to make cut marks so that the joint would fit tightly, a hand auger bored holes for the treenail or wooden peg, and reference marks were made on each beam or post end to show the proper connection points during assembly.

You can see some of these marriage marks on the sawn beams in my photo below. Typically the marriage marks or numbers were cut as combinations of straight lines to form roman numerals.

The marriage marks in the photo were on rafters in a Poughkeepsie home built in about 1790 and repaired in the 1980's by the editor [DF].

Square-rule construction ended the practice of custom-joining each pair of beam or post ends by cutting and joining timbers or other wood members using a uniform or standard joint shape and dimension.

As with later mass-production this allowed any two ends of beams or posts to be joined together, making the numbering of mating post or beam ends using marriage marks unnecessary.

While I've read that Square-rule construction became dominant in North America by 1820, I'm doubtful about how widespread it was at that time, given the many barns or other structures we date to later than that era that still used marriage marks on their posts and beams.

The timber framing shown in our photograph at above below is from an 1875 Colonial home in Newburgh, NY. You can see this house

at ARCHITECTURE, STYLE, & BUILDING AGE.

Hewing logs into beams may be older than is commonly assumed, as there is certainly prehistoric evidence that people made adzes for various purposes including farming and possibly wood-hewing.

But generally experts date hand-hewn beam construction to the 1100's in Europe, and in North America from the early 1600's into the mid 1800's, extending even to modern time by some craftspeople and timber framers.

Later beams were sawn manually or mechanically by a manually operated vertical pit saw, ultimately by machine-powered pit saws and circular saws. Timber framing using post and beam construction with mortise and tenon joint connections was used in Europe for at least 500 years before it was first employed in North America.

Saw Kerf Marks in Wood Cuts: Angled, Straight & Curved Saw Kerfs Indicate Timber or Plank Age

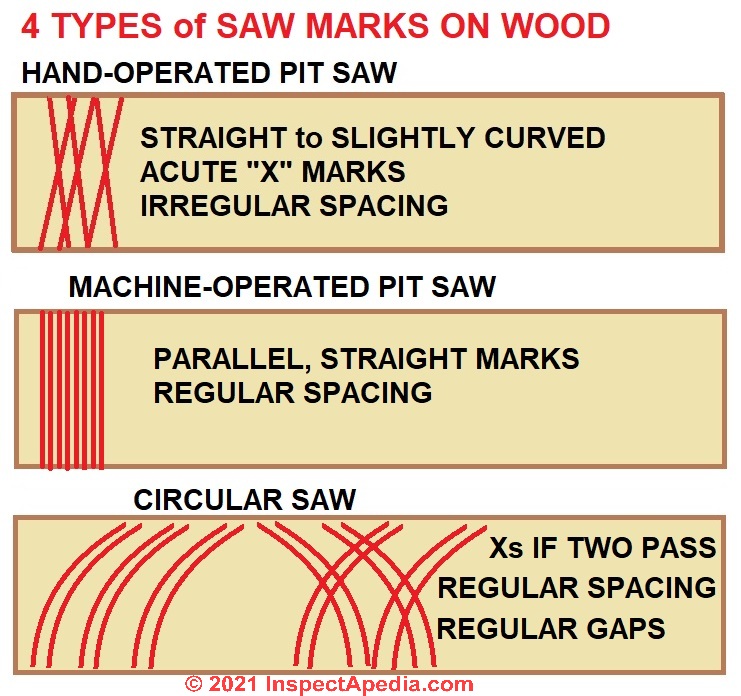

On older wood materials that were not later planed or sanded smooth, we find at least four types of saw cut marks as illustrated above. Below we include photographs of each of these types of saw cuts or kerf marks.

Taking note of the shape and regularity of saw cuts or kerfs can tell us the type of saw used to produce the lumber or beam and can give a clue to the age of the wood.

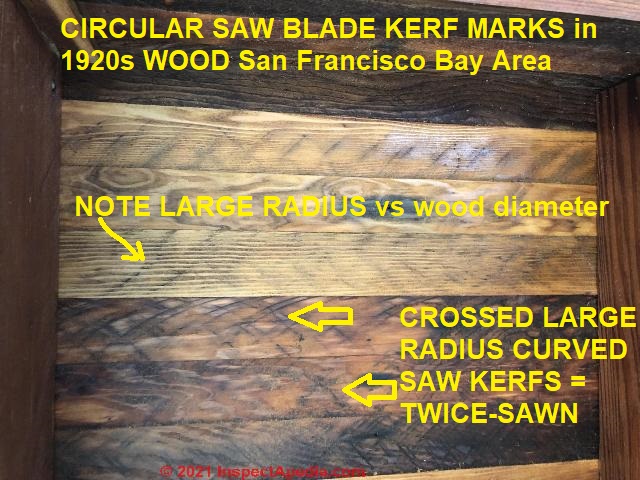

Where rounded or arced saw marks are present we can measure the arcs to estimate the size of the circular saw blade - another clue to the age of the lumber itself.

In Colonial North America, at least in the northeast where water power was available, water powered sawmills were in common use as early as 1620 when water powered sawmills cut logs into planks for colonial homes.

By the middle of the 19th century and perhaps 20 years before the U.S. Civil War, thousands of sawmills were in operation in more urban areas.

Nevertheless, in frontier areas where sawmills had not arrived, people continued to build homes and other structures from logs or rough-hewn logs as we described above.

Pit Saw Kerf Marks

Angled pit saw cut marks in wood - hand operated pit saws

The saw cuts visible by flashlight on this sawn beam form an irregular "vee" shape, a clear indicator that this beam was cut by hand using a two-person pit-saw.

Our photo shows a hand-sawn pit-saw cut beam or plank. Hand-sawn planks and beams are marked by straight saw kerf cut lines that include intersecting angles marking the "up" and "down" cuts made by the sawyer who stood on top of the log (the "up" cut) or beneath the log in the pit (the "down" cut).

This beam was cut before mechanical saws were available, but after hand-hewn beams or raw logs were in common use.

This places the age of this structure perhaps in the mid 1700's.

Above: a pit-sawn beam examined at Brinstone Farm, St. Weonards, Herefordshire, UK.

Buildings in this area date from the 1600's and hedgerows or other field markers, paths and roadways date to Roman times.

The relatively straight saw kerfs that change angle across this beam argue for this beam having been cut on a hand-operated pit saw.

Parallel pit saw cut marks in wood - machine operated pit saws

We can contrast these saw marks with the mechanical pit saw which followed, then with circular saw marks, and later with planed dimensioned modern lumber of two generations. We include illustrations of these markings and surfaces below.

Our photo above illustrates a wood member cut on a machine-operated mechanical pit saw.

In comparing the saw cut marks on this lumber with the hand-sawn wood above, you will notice that the saw kerf marks are all vertical across the wood, all parallel, and quite regular in spacing.

Depending on the location, mechanically-operated pit saws were in use as early as 1840 (in New York), later in locations further west in North America.

Above: vertical parallel saw kerf marks on wood lath of a plaster wall found in a home built in 1913 in Poughkeepsie, New York.

Unlike the hand-cut pit saw marks in our photo above, a mechanically-operated pit saw leaves vertical saw kerf marks that are parallel as the pit saw blade was moved consistently and vertically while the log was pushed slowly through the saw machine.

Also see WOOD LATH for PLASTER or STUCCO

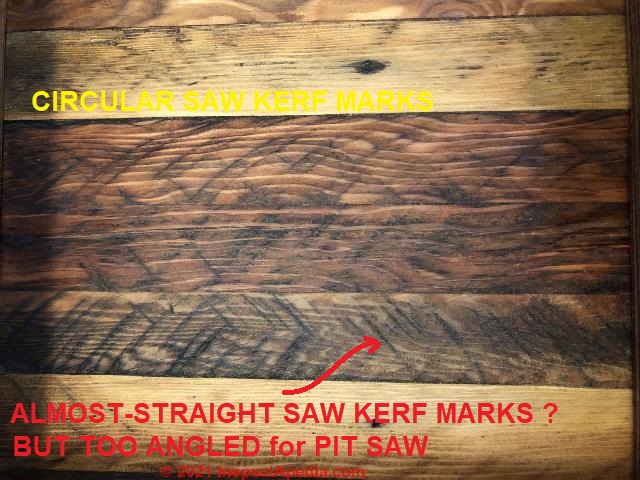

Rounded Circular Saw Kerf Marks in Wood - Early Circular Saws

How to Identify Types of Saw Kerf Marks in Old Wood:

How to Identify Types of Saw Kerf Marks in Old Wood:

Acute Xs, Wide Xs, Curved Xs, Cured Radius,

Large & small radius curves, parallel and off-parallel straight-line X's in wood

Reader Question: X-Marks in Sawn Wood Describe Cutting Method & Age?

I am curious to know about the saw marks on some redwood lath boards taken from a home built in the 1910's-1920's.

The saw marks make an "x" on the face of the lath. I have joined several pieces together and sanded them but not so much as to remove the saw marks.

My home is made of old growth redwood with the exception of the framing. I often wondered how the larger boards and beams were cut.

I regret not being able to save more of of the lath but the only way to have done so would have been to strip it off, and then reattach. However I have been able to make some nice small projects with it. - MCL 2021/07/14

[Click to enlarge any image] [Annotations added by InspectApedia.com]

Moderator reply: Curved or Arced Saw Mark Size is a clue to saw blade size & age

@MCL,

Those X-shaped saw kerfs, had they been both straight and in an X with a more-acute angle would probably have been cut from a human-powered pit saw;

but on closer analysis, nearly all of your wood's saw kerf marks appear to have some arc or curve that I will explain.

And it's perfectly common to see a mix of saw blade marks on lumber in an older building; lumber may have been reclaimed from an earlier use or it may simply have been stored and mixed at the saw mill.

Dating lumber by saw kerfs has to be adjusted not only for the country in which the lumber was cut but even the area of the country. For example in the U.S. and probably in Canada, powered pit saws, and later powered circular saws were in earlier use on the east coast of those countries than further west or on the west coasts.

The West Coast also had powered saw mills before communities in the center of the country including water-powered circular saws and possibly water-powered pit saws.

John Reed, the first Anglo-Saxon settler in Marin was an Irish settler from Dublin (b. 1805, d. 1843 from a botched phlebotomy) who became a Mexican citizen in 1834 and ultimately was assigned the first land grant north of San Francisco Bay. - source: Mill Valley Historical Society, retrieved 2021/07/21 original source: mvhistory.org/history-of/history-of-early-mill-valley/

The earliest San Francisco powered sawmill was probably John Reed's Saw Mill

... constructed in the 1830's by John Reed, grantee of the Rancho Corte Madera del Presidio.

The creek waters furnished the motive power for the mill, which was the first in the San Francisco Bay region to supply lumber. - source,

noehill.com › marin › cal0207

California Historical Landmark #207: First Sawmill in ... - NoeHill in San Francisco

It would be very useful to know the dimensions of the sawn wood in your photos; otherwise we are not sure how reliably we can distinguish between a "straight" or "angled" pit saw blade kerf mark in wood and the marks that might be left if we're looking a a narrow (perhaps just 1" wide) wood strip that was sawn and then back-sawn using a large-diameter circular saw blade.

Is it a Pit Saw or a Circular Saw Mark?

Earliest pit saws used a straight blade that moved in an alternating but straight line up and down - pulled and pushed by two workers, one standing on the log and another in the pit below the log - producing an X-type saw kerf.

Those blades sometimes had a slight arc themselves, so even a pit saw blade kerf may not be dead straight - it might have a very slight arc, but the set of kerf marks in the wood will be parallel and for a hand-operated pit saw, they form an acute X-cut as you'll see above on this page, and the cuts are not spaced at very regular intervals.

Later pit saw blades including one I found in Cold Spring New York, were mechanically driven, perhaps by water power; those blades (at least those I have seen) were straight and produced fairly straight, parallel saw

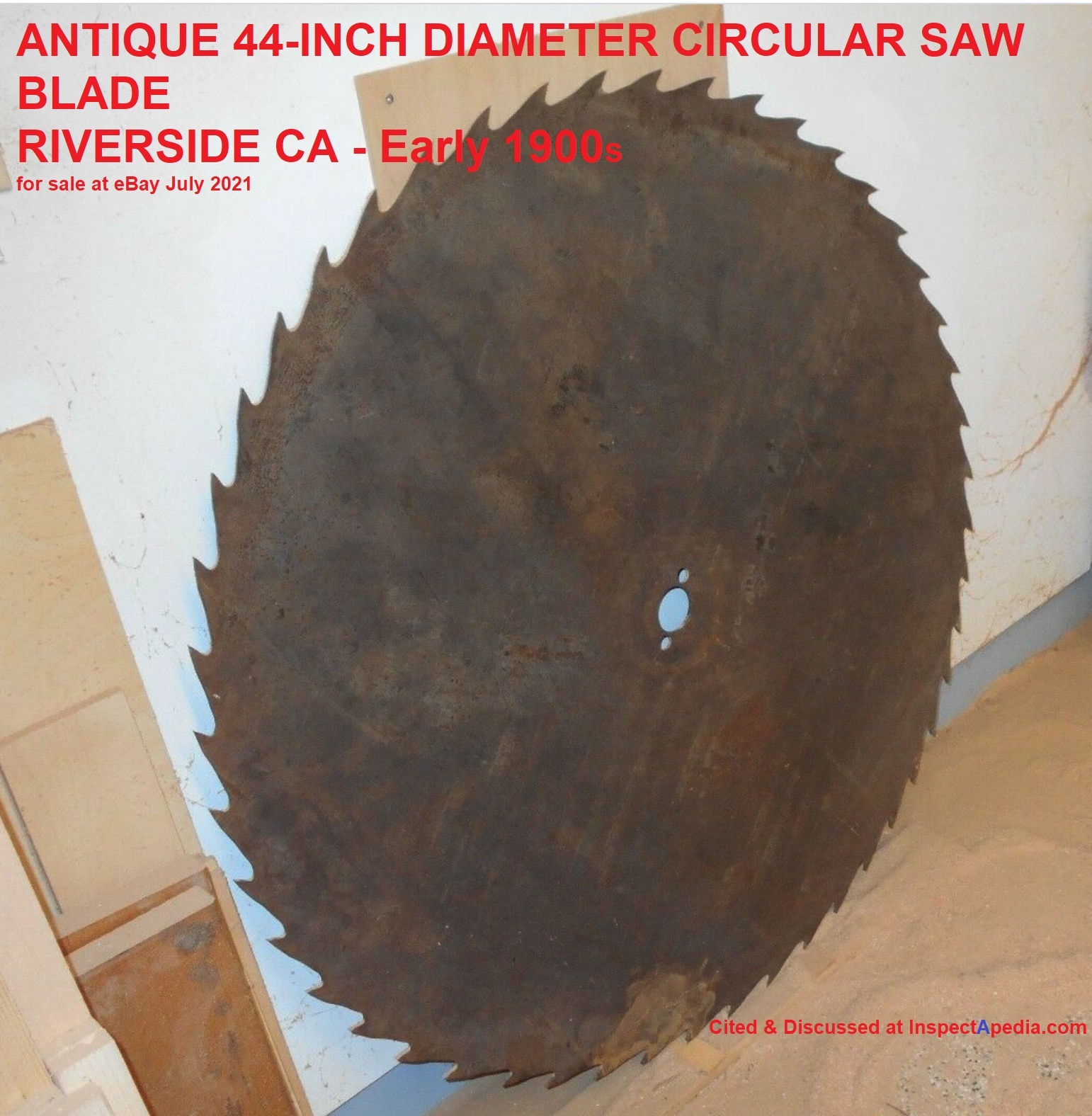

Size of Circular Saw Blade May Be a Clue to Age

Arc-shaped saw kerfs are from a large circular saw blade or even from a smaller one - we can't say without knowing the size of the wood or having some measurement reference on your photos.

But it is the case that in many communities smaller-diameter circular saw blades were in use well before those very large four-foot-diameter fellows like the antique 44-inch blade we show blow

Early circular saw blades were small and were used to cut lath and framing studs; those leave a curve that has a smaller radius or a "sharper arc" if you like.

Later saw blades got quite large; we've seen some several feet in diameter; those leave an arc with a much greater radius.

See details at SAW BLADE SIZE CALCULATED from SAW MARKS where we show how you can estimate the size of the circular saw blade that cut the wood where we see those curved arcs or saw kerfs.

Our photo above shows a 44-inch diameter saw blade dating from the early 1900s, for sale on ebay (July 2021) by a vendor in Riverside California.

At our article SAW BLADE MARKS to SAW SIZE CALCULATION ICT we explain how to calculate the diameter of a circular saw blade by measuring the rounded arc of the saw kerf marks in lumber. The ciruclar saw blade diameter can be a clue to possible age of the saw that cut that beam, post, or other lumber.

Crossed-Rounded Saw Marks Indicate Back-Sawing or Two-Passes By the Saw Blade

Where you see more than one set of arc-shaped saw kerf marks on a board the board was run through the saw mill twice; typically that was done for more-accurate sizing or occasionally to further smooth the wood.

You'll see those saw marks and methods discussed in the article above.

I've annotated two of your photos and will post it here and later up in the article above on this page.

Thanks for the great photo examples; we'll keep some of these with the article as nice examples.

PS: often we see just incomplete saw blade marks as lumber was later planed or sanded to a smoother surface.

Rounded circular saw cut marks in wood - modern sawmills

At above left we illustrate lumber cut on a circular saw mill. You will see that the saw kerf marks are all rounded or curved, and parallel to one another.

Now a hand saw might also leave somewhat "rounded" saw cur marks on lumber depending on how the sawyer moved his/her saw. But hand sawn kerf marks will be irregular in the curvature and will not be neatly parallel to one another.

The radius of the curve of the circular saw cut marks in this beam is quite large - that is, the round saw blade marks are flattened on the lumber, indicating that this was a large-diameter saw blade.

Lumber that was cut on smaller -diameter saw blades will, of course, show saw marks whose rounded radius is smaller as well.

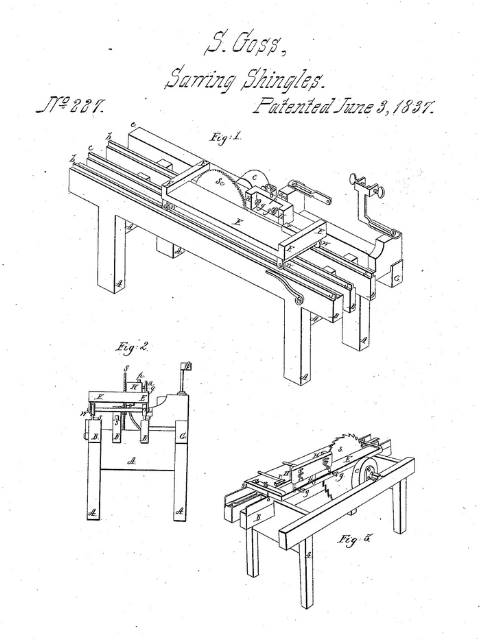

The history of circular saws and thus our ability to date lumber from circular saw cut marks is an open argument among experts. Ball (1975) notes claims of invention of the first circular saw in England in 1791 and still earlier reports of circular saw use in England in 1777. But the same author cites reports of circular saw blades in use in Holland in the 1500's.

The history of circular saws and thus our ability to date lumber from circular saw cut marks is an open argument among experts. Ball (1975) notes claims of invention of the first circular saw in England in 1791 and still earlier reports of circular saw use in England in 1777. But the same author cites reports of circular saw blades in use in Holland in the 1500's.

A better approach in understanding the age-significance of circular saw cut marks on timbers is to try to pin down when circular saws were in use in a specific area.

At left, an illustration from Goss' 1837 shingle saw patent.

[Click to enlarge any image]

In North America mechanized equipment use generally moved from the east coast westward. Earliest use of circular saws is likely to appear on the eastern seaboard, probably in New England, as early as 1800 (Matchell 1813, Rees 1819) but in my OPINION more commonly throughout the eastern U.S. after about 1830.

It's also important to understand that the use of axes, adzes, hand saws, manually-operated pit saws, mechanical pit saws, and circular saws would have been used in overlapping eras.

I look at the area where timbers were probably cut and the distance from that area to the nearest larger city to infer that saw cuts would have been by a portable machine used in building or in very small saw mill operations versus larger sawmills that would have moved to mechanized and faster circular saw cutting methods.

Our patent research on circular saws in the U.S. found circular saw sophistications being patented by Wisconsin inventor as early as 1877 that tells us that they were in use before that time and that circular saws were in use through the U.S. at least as far as the mid-west and probably further west.

Early stationary sawmills were most likely found in New England in the very late 1700's where they could be located by streams providing water power for mills. (Smeaston 1796).

John A. Miller's circular saw patent described his improvement as follows:

... the use of perforations through the saw, for the purpose of securing a circulation of air through the disk to the saw to prevent its becoming hot; also, to the form of the perforations or slots, which reduces their liability to become clogged with sawdust, Sac.

When slots are employed the rear edge only need be sharpened or beveled, though there is no objection to beveling the front edge, and may be an advantage in doing so in a direction parallel with the bevel of the rear side.

It is not absolutely essential, but is preferable, that the sharpened edges of the slots should alternate that is, each alternate slot should present its sharp edge from opposite sides of the saw.

The perforations should extend from near the center about two-thirds or more of the distance to the circumference of the saw.

The perforations may extend in curved lines or be irregularly placed.

It is desirable to have them beveled from Opposite sides of the saw alternately, so that the air will be drawn through alternate perforations in opposite directions, thus creating a circulation by which the saw will be kept cool and expansion avoided.

Our photo illustrates circular saw blade marks that may indicate lumber from two different sawmills or at least two different circular saws, as the radius of the curved lines appears different in the lumber at left from that at right in the picture.

Keep in mind that lumber within a single building may show a variety of saw cut mark types and ages.

That is because lumber may have been re-used or may have been cut at various times and at different mills but all may have been used in a single structure.

Also a old building that has been repaired, remodeled, or expanded and extended is likely to contain wood cut at different times and using different generations of equipment and sawing methods.

History of Circular Saws & Saw Patents Helps Date the Age of Saw Cuts in North America

Illustration: these circular saw marks in what is probably original subflooring in a Beacon New York building (ca. 1870) have been sanded smooth and left in place as finish-flooring.

The brick structure, located on upper Main Street in Beacon was most-likely built using the same locally-produced bricks as were used for an enormous amount of construction in Manhattan after the U.S. Civil War, and wood for the interior structure would have come from local saw mills.

Beacon, first settled in 1709 is on land "purchased" from the Wappinger tribe by Francis Rombout and Gulian Verplanck, fur traders whose names decorate various features in the Hudson River valley, especially in Dutchess and Ulster counties.

Early construction in what was then "Fishkill Landing" and Mattewan dates from about 1718.

- Ball, Norman. "Circular saws and the history of technology." Bulletin of the Association for Preservation Technology (1975): 79-89.

- Bobbins, H. "Machinery for trimming straw braid." U.S. Patent 1,984, issued February 18, 1841. -

Two circular saws O P are arranged on and revolve with the shaft L L being placed at proper distances apart. These saws are for cutting off the long and short ends which occur in braiding straw. - Clark, Henry William. "Circular saw." U.S. Patent 464,855, issued December 8, 1891.

- Cooke, Matthew, THOMAS MACHELL, WILLIAM BOWLER, THOMAS PERRY, John Robert Scott, William P. Jones, Thomas Thatcher et al. "PAPERS IN MECHANICS." Transactions of the Society, Instituted at London, for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures, and Commerce (1812): 143-189.

... which the saw shall penetrate in cutting. The very singular property of this annular or circular saw, in cutting deeper than its centre, renders it likely to prove of great utility in a variety of surgical and mechanical operations. - Gay-Lussac, M. "LXV. On the changes of colour produced by heat in coloured bodies." The Philosophical Magazine: Comprehending the Various Branches of Science, the Liberal and Fine Arts, Geology, Agriculture, Manufactures, and Commerce 41, no. 182 (1813): 430-434.

This discussion describes heat produced in circular saw blades among other items. - Goss, Samuel. "Improvement in machines for sawing shingles." U.S. Patent 227, issued June 3, 1837.

- Grey, Sylvester P. "Circular saw." U.S. Patent 411,189, issued September 17, 1889.

This invention relates to that class of circular saws having a detachable tooth-section; and its object is to enable the set of teeth of such a saw to be renewed or the diameter of the saw changed, at pleasure. - Grill, Gotfried, "Circular Saw Guard", PatentedJuly '11, 1882 U.S. Patent No. No. 261,090

The object of my invention is to provide a circular-saw guard designed to prevent injury to the operator, and to shield the teeth of the saw above the table without concealing them, and adapted to yield, so as to admit of its use without the necessity for adjustment in sawing various thicknesses of lumber. - Hoover, Francis M. "Saw-guard." U.S. Patent 545,504, issued September 3, 1895.

- Machell, Thomas. "LXIV. Description of an annular saw, calculated to cut deeper than its own centre." (1813): 428-430.

- Miller, John A., "Improvements in Circular Saws", US Patent 212,813, 1879 - filed 1877, Winnebago Wisconsin.

- Mills, Coralie M., Anne Crone, Cheryl Wood, and Rob Wilson. "Dendrochronologically dated pine buildings from Scotland: the SCOT2K native pine dendrochronology project." Vernacular Architecture 48, no. 1 (2017): 23-43.

Abstract:

The SCOT2K project has extended native pine tree-ring chronology coverage for Scotland to enable reconstruction of past climate and for cultural heritage dating benefits. Using living trees from multiple locations in the Highlands and sub-fossil material from lochs, a network of five regional chronologies has been produced.

The project has developed the application of Blue Intensity (BI), a proxy measure for maximum latewood density, which is faster and less costly to obtain than traditional densitometry measurements. The use of both ring-width and BI has been demonstrated to greatly assist historical dendro-dating of pine.

This paper presents the dating results for the twenty Scottish pine buildings or sites dendro-dated through the SCOT2K project.

They range from the fifteenth to the nineteenth centuries, and from high-status castles to modest cruck cottages. They are mostly located in the Highlands where Scots pine occurs naturally, although an early example of long-distance transport is also identified. - Morgan, Jonathan. "Arrangement of circular saws for preparing blocks for matches." U.S. Patent 1,203, issued June 27, 1839.

- Rees, Abraham. The cyclopaedia: or, Universal dictionary of arts, sciences, and literature. Vol. 22. Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme & Brown [etc.], 1819.

This book describes early use of a circular saw"

It is a circular saw, whose spindle is ... mounted, as to move in any direction parallel to itself; the saw all the while continuing in the same plane, and revolving rapidly upon its axis, cuts the wood it is presented to, and as it admits of being applied at first on one side, and then on ... - Rowe, George, and James Trunnel. "Circular saw." U.S. Patent 635,509, issued October 24, 1899.

- Sill, Joseph. "Saw-guard." U.S. Patent 302,041, issued July 15, 1884.

- Smeaton, John. Experimental enquiry concerning the natural powers of wind and water to turn mills and other machines depending on a circular motion: And An experimental examination of the quantity and proportion of mechanic power necessary to be employed in giving different degrees of velocity to heavy bodies from a state of rest. Also New fundamental experiments upon the collision of bodies. With five plates of machines. Printed for S. and J. Taylor, 1796.

- Woodwoeth, William. "Worth." U.S. Patent 80, issued November 15, 1836.

Dimensional lumber - machine cut and machine planed lumber

Modern dimensional lumber in North America was cut at speeds and using equipment that no longer left vertical or rounded saw kerf marks on the wood.

Modern dimensional lumber in North America was cut at speeds and using equipment that no longer left vertical or rounded saw kerf marks on the wood.

Into the 1930's, dimensional lumber (2x lumber, or 2x4's, 2x6's, 2x8's etc.)

was actually cut to a size quite close to its nominal dimensions: that is, a 2x4 was close to 2" x 4" in cross section.

By 1940 dimensional lumber was cut and planed to a smaller actual size. A modern 2x4, for example, is about 1-1/2" thick by 3-1/2" wide.

Our photo (left) illustrates a modern kiln-dried 2x4 wall stud, cut and planed to a smooth-surfaced dimension of 1-1/2" x 3-1/2".

Actual dimensions of modern 2x lumber vary, and vary more widely depending on whether or not the members are kiln-dried (more likely to be exact in width)

or pressure treated (still wet) or not kiln-dried SPF (Spruce Pine Fir) lumber.

Also see BALLOON FRAMING

and see PLATFORM FRAMING

and PRE-CUT LUMBER CONSTRUCTION & LEAVITTOWN

History of the Mechanically-Operated Reciprocating Saw used for Cutting Beams, Lumber & Other Wood Products

Reader Question: How did you come up with 1840 as a date for the adoption of mechanical Pit Saws?

14 Feb 2015 Anonymous said:

Where did you find out that mechanical pit saws were first adopted in 1840? I'm looking for reference material on the history of up-down mechanical saws.

Reply:

Thanks for the question about the history of Pit Saws. Here are citations giving key inventions and dates in the development of the reciprocating saw that I’ve seen as a mechanical improvement over the hand-operated pit saw described in this saw-kerf type identification and aging article. Before I wax eloquent on the pit saw and the mechanically-operated reciprocating saw (starting in the U.S.)

There is of course no single correct date for the first use of mechanical pit saws as the movement of mechanical tools in the U.S. was generally from East to West over quite a few years. I mean to say that on the East Coast, perhaps earliest imported from Europe, various tools usually appeared first.

I have to add that the relatively-straight-bladed reciprocating saw co-existed with circular saws in many areas.

However I think that perhaps it was possible to drive a reciprocating saw with less speed and less energy and thus to make slower, if more easily portable sawmills with this design than by using circular saws that would have needed more power - say from a millstream.

Crosby patented reciprocating saw designs for a portable saw mill in the 1838 and 1842. Another source of my dating of the Pit Saw to before 1841 is the Wemmel patent from 1841. Also personally I have observed the saw cut marks on what other evidence argued was original wood framing in buildings I’ve inspected and dated to about 1840 in New York.

Patent History of Reciprocating Lumber Saws in the U.S. before 1900

With all that whining done, it's instructive to look at early patents for patents on lumber saws in the U.S. (there is additional history for such tools in other countries of course, and one can dig up patents from the U.K., Norway etc.)

The first patent granted in the U.S. was in 1790 Patent No. 1 on July 31, 1790, for an improvement "in the making Pot ash and Pearl ash by a new Apparatus and Process."

In understanding the reciprocating saw and the pit saw, here are some relevant saw patent citations from 1900 and earlier. I've ordered these with earliest lumber saw patents at the bottom of the list.

Farr, Freeman S. "Double-acting band-saw mill." U.S. Patent 640,458, issued January 2, 1900.

Shuls, Frederic W. "Set-works for sawmills." U.S. Patent 652,727, issued June 26, 1900.

- Prouty, William B. "William b." U.S. Patent 622,536, issued April 4, 1899.

Pertains to crescent saws, mis-spelled in the electronic scan as “@ressent-saws” - Prescott, George W. "George w." U.S. Patent 408,669, issued August 6, 1889.

describes a reciprocating “gang saw” - Mcevilla, Heney. "Reciprocating-saw mill." U.S. Patent 339,000, issued March 30, 1886.

- Weight, A. "Improvement in saw-mills." U.S. Patent 48,349, issued June 20, 1865.

- Worthen, S. A. "Crosscut-sawing machine." U.S. Patent 30,904, issued December 11, 1860.

- Germann, Christian. "Reciprocating saw." U.S. Patent 29,688, issued August 21, 1860.

This patent is of special interest to me since Germann is also my Grandfather’s name, though Henry was in New Orleans while the inventor of this saw was Christian Germann from Camden Michigan.

Since this patent describes an “improvement” over existing reciprocating or pit saws, it’s a fair argument that these “rectilinear saws” were pre-extant. The patent did not apply to circular saws. - Aenold, Aza. "Saw fob sawing machinery." U.S. Patent 15,163, issued June 24, 1856.

describes a mechanically-operated reciprocating saw:

My invention consists in the application of certain devices to the two edged double reciprocating sawmill, in such manner as to enable the mill to perform not only more and better work in a given time but to do it with less manual labor.

For this purpose I use a two edged saw, that is one having teeth on both sides in order to cut a board at each move of the carriage, to right and left. - Knowles, Hazard. "Hazard knowles." U.S. Patent 7,603, issued August 27, 1850.

describes improvements to the teeth of a circular saw - Kunsman, Jacob. "Feeding sawmills." U.S. Patent 5,059, issued April 10, 1847.

- Marsh, Thos. L., (Liberty, Indiana), “Fob [sic] cross-sawing timber” probably “For Cross-Sawing Timber.” U.S. Patent No. 3287A, Sep 28, 1843,

[excerpting] a new and useful improvement in the machine for sawing logs, timber, and other articles called the western wood-Sawyer 7 , describes a mechanically-operated reciprocating saw. - Crosby, Pearson. "Portable sawmill." U.S. Patent 2,804, issued October 7, 1842.

- Goodell, Frederick. "harvey." U.S. Patent 2,328, issued November 3, 1841.

- Wemmek, Nilson J. “Apparatus for Filing saws." U.S. Patent 2,011, issued March 18, 1841.

- This patent refers to a special filing apparatus used for reciprocating saws (vertical pit saws for example) - Pepper, Hakt. "Southwick." U.S. Patent 1,313, issued September 3, 1839.

- Crosby, Pearson. "Portable sawmill." U.S. Patent 771, issued June 7, 1838.

… county of Chautauqua and State of New York, have invented a new and useful Improvement in Machines for Sawing Timber, called Crosbys Portable Prairie Sawmill,

This patent describes a portable reciprocating saw mill by Pearson F. Crosby from Fredonia, New York.

Early Tools including Saws used in the U.K. and in North America

- Arthur, Eric and Dudley Witney. The Barn: A Vanishing Landmark in North America. Greenwich, CT: New York Graphic Society Ltd., 1972.

- Auer, Michael J., THE PRESERVATION of HISTORIC BARNS [PDF] Preservation Brief No. 20, US NPS, retrieved 2022/10/07, oeiginal source: https://www.nps.gov/tps/how-to-preserve/briefs/20-barns.htm

- Fitchen, John. The New World Dutch Barn: A Study of Its Characteristics, Its Structural System, and Its Probable Erectional Procedures. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1968.

- Clark, Victor Selden. History of manufactures in the United States: 1607-1860. Vol. 1. Carnegie institution of Washington, 1916.

- Halsted, Byron D., ed. Barns, Sheds and Outbuildings. New York: O. Judd Co., 1881. Rpt.: Brattleboro, VT: Stephen Greene Press, 1977.

- Hewett, Cecil A. "Anglo-Saxon carpentry." Anglo-Saxon England 7 (1978): 205-229.

- Humstone, Mary. Barn Again! A Guide to Rehabilitation of Older Farm Buildings. Des Moines, IA: Meredith Corporation and the National Trust for Historic Preservation, 1988.

- Klamkin, Charles. Barns: Their History, Preservation and Restoration. New York: Hawthorn, 1973.

- Lubar, Steven. "Culture and technological design in the 19th-century pin industry: John Howe and the Howe Manufacturing Company." Technology and culture (1987): 253-282.

This author puts early circular saws as early as 1847 but patents suggest earlier dates. - Peterson, Charles E. "Sawdust Trail, Annals of Sawmilling and the Lumber Trade from Virginia to Hawaii via Maine, Barbados, Sault Ste. Marie, Manchac and Seattle to the Year 1860." Bulletin of the Association for Preservation Technology (1973): 84-153.

- Samson, M. David. "SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN AS A MID-NINETEENTH CENTURY MIDDLEMAN: THE PERIODICAL’S ROLE AS A LIAISON BETWEEN THE PUBLIC AND INVENTORS." PhD diss., Worcester Polytechnic Institute, 2014.

cites Advertisement for Circular Saws from an 1868 Scientific American magazine. - Schultz, LeRoy G., comp. Barns, Stables and Outbuildings: A World Bibliography in English, 1700-1983. Jefferson, NC, and London: McFarland and Co., 1986.

- Thomson, Ross. Structures of change in the mechanical age: Technological innovation in the United States, 1790–1865. JHU Press, 2009.

- Welsh, Peter C. Woodworking Tools, 1600-1900. 1966.

- Wood, James L. "The Introduction of the Corliss Engine to Britain." Transactions of the Newcomen Society 52, no. 1 (1980): 1-13.

Modern framing lumber is provided in these dimensions:

Table of Modern Framing Lumber Dimensions |

|||

| Nominal Size (Inches) |

Kiln Dried Size (S4S - smooth) |

Pressure Treated (wet) Size (SYP) "S4" Extended Life Lumber | Rough Cut not Kiln Dried Size |

| 2x2 | 1-1/2 x 1-1/2 | Actual size in depth (width) varies +/- 1/4" | Actual size in depth (width) varies +/- 1/2" |

| 2x3 | 1-1/2 x 2-1/4 | ||

| 2x4 | 1-1/2 x 3-1/2 | ||

| 2x6 | 1-1/2 x 5-1/2 | ||

| 2x8 | 1-1/2 x 7-1/4 | ||

| 2x10 | 1-1/2 x 9-1/4 | ||

| 2x12 | 1-1/2 x 11-1/2 | ||

| 4x4 | 3-1/2 x 3-1/2 | ||

| 6x6 | 5-1/2 x 5-1/2 | ||

- See DIMENSIONAL LUMBER and

also FRAMING AGE, SIZE, SPACING, TYPES - Plank house construction & traditional Yuroak split redwood plank house construction are described

at PLANK HOUSES. - Hewn beams and adze cut marks are described

at HEWN BEAMS & PLANKS

Case Study: Lumber Saw Cut Marks & Door & Lock Hardware, Foundation, Trim = Age of pre-1900 Home in Arkansas

This discussion and photos of a home in central Arkansas,courtesy of readers R and T, illustrate the value of considering all available building details and components when estimating the age and reviewing the history of a building. That approach is more-complete than considering the lumber cutting method or saw kerf marks alone. - Ed.

We love your website. I have looked at it many times over the last 2 years and thought today that I should email you to get any thoughts that you might have on. -what year this house could be,- should you be so kind to respond to us.

[Click to enlarge any image]

We are working on a house in West Central Arkansas. We are trying to determine the year and have been looking closely at details still remaining in the house.

Honestly I am completely stumped. I suspect it was built around 1885-1890 but I still really don't know!

Today I was in the basement and looked at some of the beams below the kitchen floor. [Photo below]

I am curious as to whether these saw cuts look like circular saw kerfs to you or those from a pit saw.

We have found door latches from 1888,

1897, 1898 and cabinet hardware from 1890s.

The front door has a metal "letters" door (for mail) with a stamp used from between 1852 and 1901.

The house has gas pipes in each ceiling for the no longer present gas lamps.

In the root cellar, a chimney goes down from the kitchen, appearing as if there were a boiler or coal furnace there at one time.

There is also a rectangular "pond" in the back yard that I suspect may have been a saw pit (?).

We were told the house was built in 1905 but I strongly suspect it was built earlier. The foundation piers in the center of the house are limestone blocks (random shapes). Here are photos of the house and some saw marks!

Any thoughts on possible years or about when pit saws went out of use would be really great and very appreciated. I did notice that a large saw mill was present in this town in 1889.

The last 3 photos are boards below the kitchen. I wonder if the kitchen may have been added later and perhaps the brick structure behind the house was the kitchen (?) - Anoymous by private email 2020/07/09

Moderator reply:

Some of the interior woodwork and the general architecture are similar to homes built at the turn of the last century but I agree that the house could well be older than that.

When researching and guessing house age based on saw cuts, as you've already begun to research, knowing the history of when local sawmills went up is important. The earliest round bladed sawmill operations were on the U.S. East coast, migrating westward with time.

The saw cuts in the joists are certainly from a circular saw, but the floorboards overhead were cut using a pit-saw, as I think you had already noticed.

That's no surprise; explanations include use of both types of sawn lumber as what was available in-stock at time of construction and/or the fact that it's no surprise that on a home dating from the 1880s or earlier will have been repaired or even had a floor support re-framed from time to time.

Lumber used in construction is usually brought from the closest source. So researching the history of local lumber mills is useful.

Gas piping was often added to homes when that became available - a subtlety that can be investigated best when there's some reason to open a wall or floor to give access to the piping routing and connections.

(Adding pipes in walls requires some demolition and repair). Combining those clues along with a history of local gas availability can be useful in writing the history of the home.

You've done a great job on hardware.

When working on the home, in addition to watching for actual documents, sometimes I find an old newspaper stuffed into a wall or used as a draft barrier, and on occasion a pencilled note written on the hidden surface of sheathing or other materials by a builder.

The brick kitchen is almost certainly newer, both from the style and texture of brick and the window style and framing (from outside). Take a look at the plumbing materials and also at the mortar used with the brick. (Older is usually softer with less portland).

Watch out: that gas meter along an alleyway is exposed to vehicle impact and could blow up the whole neighborhood. You probably want to install some protective bollards

See details at PROTECTION BOLLARDS for MECHANICAL EQUIPMENT

If you like we can find a spot or two to include some of your photos in appropriate articles at InspectApedia to invite reader comments such as on age determination. Our default is to keep you anonymous unless you ask otherwise.

Reader follow-up:

Thank you so much for the very well-thought-out and detailed email! I did not expect such a great and comprehensive response from you and I do appreciate the time that you took to sit down and write that!

We would be happy to allow some of our photos to be included in your website. Just don't use our names! 😀 South Central United States/western Arkansas.

So from what you see do the years 1885 to 1890 sound too old or possibly correct? It's so difficult to pinpoint, I know.

Since we do have rock faced block on the outside of the house, it leads me to believe that it is probably no earlier than 1885. The earliest homes I have found in this area with rock face block foundations are about 1885/6.

Not that someone couldn't have changed an old limestone foundation later - I have seen some of the older local homes here with newer cinder blocks placed under them for foundations!

-- It's so difficult with upgrades that people make over the years!

So this is where your site has been very nice for us! Seeing the saw cuts and comparing them has made me believe it could be older than 1905. Seems like the lowest parts of the house can at least be true to original build.

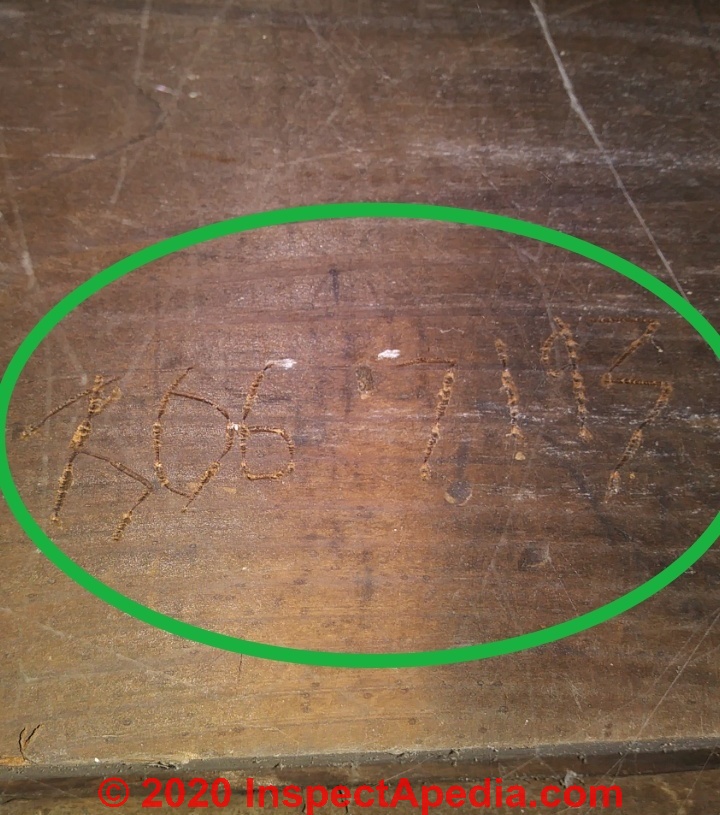

We did find what looks like "Bob 7193" on a beam in the basement.

The carved wood molding that looks like egg & dart - I found to be called "heart leaf," a style from the 1880s having been found originally I think on a Greek temple.

We found some square looking nails in the dining room wallpapered wall - see detailed nail aging procedures

The muntin profile photos are in the garage which shows evidence of once having had transom bottom opening 6 pane windows.

(Muntin profiles I've looked at/matched up online seem crazy to me - 1840s?)

For the gas lights, (ceiling pipe shown before chandelier went in dining room) - the earliest reference I've found is 1887 for gas lighting installed in this town - there was a newspaper article on someone who had their whole house done in gas in 1887.

Oh also - many of the floor and attic boards are black walnut.

Below are pics of what may or may not be "Bob 7193" if you zoom in to the shots. The carved in digits are above the beam over the bricks.

Moderator reply:

More research points?

How does this house compare with others nearby? is it older, newer, same? What do we know about the history of the street? What are the foundation materials? Is the whole house over crawlspace? What debris can you find there?

I'd like to know when gas lighting was first available in the town where this house is located.

And I'd look for framing details that might tell us about modifications or repairs;

That tack seems to have a very sharp machine-made edge. If you've not already seen it, take a look at

Also, I've found very old components sometimes in newer buildings - often people re-used lumber or beams from older structures. So the answer and research are a bit muddled.

History of the Vulcan lock by Yale & Towne Mfg. Co.

Are there patent numbers on that Vulcan lock? That was produced by Yale & Towne Mfg. Co., offering some date borders as does the history of the Yale lock company - https://www.locksmithdoncaster.co.uk/advice/the-history-of-the-yale-lock/

Are there patent numbers on that Vulcan lock? That was produced by Yale & Towne Mfg. Co., offering some date borders as does the history of the Yale lock company - https://www.locksmithdoncaster.co.uk/advice/the-history-of-the-yale-lock/

Excerpts:

Although the History of the Yale Lock has a very British flavour, it’s origins are over the pond in America. It was the Yale family who invented the Yale Lock, which is essentially a pin tumbler lock. Having already invented the Cylinder lock in 1848, it was Linus Yale, Jr. who invented the pin tumbler lock in 1868, along with Henry R Towne.

The original lock company which invented the Yale lock was called Yale Lock Manufacturing Co and was based in Connecticut in America. The company name was later changed to Yale & Towne, where they registered 8 patents for their pin tumbler safe lock, safe lock, bank lock, vault and safe door bolt and padlock.

- Taylor, Warren H., THE YALE a[sic] TOWNE MANUFACTURING COMPANY, 1891. This is a reissue letter of patent March 17, 1892, original no. 403,705, dated May 21, 1889, SN 248,823 - attached

More of that company's lock patents may be interesting - look for these on your house

- Taylor, Warren H. "Master-key lock." U.S. Patent 652,337, issued June 26, 1900.

- Taylor, Warren H. "Latch." U.S. Patent 685,188, issued October 22, 1901.

- Taylor, Warren H. "Pin-lock." U.S. Patent 758,026, issued April 19, 1904.

- Augenbraun, Peter F. "Duplex or master-key lock." U.S. Patent 912,773, issued February 16, 1909.

- Schoell, Reinhold. "Pin-tumbler lock." U.S. Patent 917,365, issued April 6, 1909.

- Ballou, Waldo R. "Padlock." U.S. Patent 686,882, issued November 19, 1901.

- Lawrence, Alfred. "Mortise-lock." U.S. Patent 950,108, issued February 22, 1910.

- Recent sale of what looks like the lock in your photo

https://www.worthpoint.com/worthopedia/antique-mortise-lock-junior-vulcan-1791236148

Reader follow-up:

Yes! Here is a picture - this one I figure is from 1897 (last date) and 2 others say 1898. Those are downstairs in one room, upstairs and also in that same room are many rim locks / box locks which were made by the chantrell tool co in the late 1880s.

Another lock at the root cellar door we matched to one from the 1850s, only by shape however and it may not have been original to that door (other screw holes were present).

Thanks for the cool info on locks! I went crazy last year digging through their old catalogs that I found somewhere on the internet. I took apart our front door lock and found that the internals date from 1890 to 1910, with no specific differences to isolate early vs late.

Seems to be a lot of that, same items spanning that gap of years from 1890 to 1910.

Thank you for your thoughts on the gas meter in the alley. I have often thought the same thing that you have. I will be calling the gas company about that to have some kind of a bar setup put around it. It's really scary!

On the gas lighting; from what I read previously, natural gas was first found here in 1885-7.

This residential block was established with the city in 1887.

Also I found remnants of old cedar shingles on the roof.

Outside there are clay pipes in the ground next to the house and beside the carriage house/brick structure. (few pics of the pipes)

The foundation material below the house in the middle of the main structure is limestone with mortar. The outside is rock faced block with "rope(?) joints" (pic)

The main house is all on crawlspace, with only the kitchen having a root cellar below it.

Moderator reply:

RE: " The outside is rock faced block with "rope(?) joints" (pic) "

Those look like form-cast concrete blocks - if so that's a later foundation material, possibly 1920s to 1960s.

I'd look for evidence the foundation was repaired, rebuilt, modified.

The old clay pipes may be from a prior septic or drain system.

Reader follow-up:

In this region, there are numerous houses with rock faced block foundations known to have been built in the 1880s.

Just pulled a lock off of the basement door. Looked up the mark; Russell & Erwin. Dates to between 1846 & 1851. Looked like it has been there forever, having even dropped 3/4 of an inch from its keeper, just like the door it came off has!

Who knows when the core structure of this place was built!

Moderator reply:

That's so helpful; all of the formed block homes I've inspected were much newer. I'm puzzled about how the home foundations you cite date between 1846 & 1851.

Perhaps some discussion can get to some more detail on this historical detail.

The earliest patent I've found for finished block faces was by Wight in 1906 though of course there would have been versions before his patent, and my search was not exhaustive.

Portland cement, critical in the fabrication of concrete blocks, dates from 1824 in England (Joseph Aspdin).

From sources I've read, the first hollow-core concrete blocks date from 1890 (in the U.S. - Harmon S. Palmer) who didn't patent his design until 1900.

The product was a tremendous success, such that within 5 years of that patent there were many companies producing such blocks. Some of my early research in New York included talking with (now deceased) Henry G. Page (Poughkeepsie) who started a construction business after WWI by making his own concrete blocks.

Henry's blocks were famous among inspectors because he sometimes shorted on the portland and the blocks, after a few decades, were rather crumbly. Henery and other block manufacturers used a hand-casting machine - it was very labor intensive. His blocks were set up on the family farm property on Rte. 55 - now a pit, partly dug by soil he used for his block-concrete mix.

Research on the

History of Concrete Blocks & Finished-Face Concrete Block

- Koski, John A. "How Concrete Block Are Made." Masonry Construction, October 1992, pp.374-377.

- Macbeth, Jeremont. "Concrete-wall construction." U.S. Patent 938,678, issued November 2, 1909.

- Rice, Harmon Howard, and William M. Torrance. The Manufacture of Concrete Blocks and Their Use in Building Construction. New York: Engineering News, 1905.

- Seamans, Edward W. "Mold for concrete blocks." U.S. Patent 720,536, issued February 10, 1903.

- Schierhom, Carolyn. "Producing Structural Lightweight Concrete Block." Concrete Journal, February 1996, pp. 92-94, 96, 98, 100-101.

- Tubesing, William F. "Machine for making concrete blocks." U.S. Patent 868,730, issued October 22, 1907.

- Yeaple, Judith Anne. "Building Blocks Grow Up." Popular Science, June 1991, pp. 80-82. 108.

- Wight, George C., and Theodore V. Galassi. "Finishing the faces of concrete blocks." U.S. Patent 837,165, issued November 27, 1906.

see https://inspectapedia.com/structure/Wight-Patent-US837165.pdf

Excerpt:

Our invention relates to the construction of concrete blocks and producing upon the surface of such blocks a representation of a granite finish.

Most of your excellent photos belong elsewhere, but the foundation discussion fits for now at

FOUNDATION MATERIALS, Age, Types

where I will include a redacted (to respect your privacy) version of this discussion .

Reader follow-up:

Thank you for that quite amazing email!

I think I must have confused you with my prior ramblings; the lock on the basement door (a Russel Erwin lock-see pic of black "RE co" stamp) dates between 1846 and 1851. (Not the outer foundation block)

There is also a Russel Erwin manufacturing co New Britain stamp on our front door letters slot. (Picture included) That stamp ran from 1851 to 1902.

**The earliest block I have seen here - the foundation blocks are on buildings from 1885/1886.

1890 seems about right for the house but the neighbor showed us an abstract that mentions "Lot 10" (which is this lot) and there is a statement showing construction here in 1888 on lot 10.

Dating this structure has been VERY confusing to say the least and I really really appreciate your thoughts. Thank you so much for the information you've shared! Great info on the concrete stuff.

Moderator reply:

It would be no surprise that an original Foundation, possibly made of Fieldstone, may have been rebuild or faced over the life of such a home. See if you can see construction details that include older Foundation components. I think that will help understand the history of the Homes Construction, repair, and modifications

Reader follow-up:

I think you just nailed it. Please take a look at these pictures which I took a while back. The central foundations are completely different from the outer ones.

These "piers/stacks" are in the center part of the main house. Please notice the "red brick with other blocks behind bricks" photo; I've wondered about that since I first saw it. (Up above that is a fireplace having more recent brick- I'll include a pic of that fireplace)

Another detail below the kitchen:

I circled in green a photo where we found what looks like "Bob 7 1 93" under the main beam and later looking brick pier below the kitchen.

We have pondered whether the "Bob 7 1 93" was scratched in when the kitchen was added, or original build date for the whole house, or even if it is just some phone number! Below the beam with the "name" on it is another beam which appears to have 4 vertically scratched marks followed by two vertical marks which also look like they were intentionally carved in.

That beam looks quite old. At first I thought that this beam would be fastened to another beam that also had the same corresponding "four plus two marks" on it but the beam above it does not have anything like that, at least not that I've noticed.

Ok I hope that all makes sense. If anything needs clarification please let me know!

...

I just found 2 other pics of the "brick faced old masonry." Our plumber snapped these shots for us. They are below the fireplace which I sent you a photo of in the preceding email that I sent you today.

...

Reader Comments, Questions & Answers About The Article Above

Below you will find questions and answers previously posted on this page at its page bottom reader comment box.

Reader Q&A - also see RECOMMENDED ARTICLES & FAQs

How do we make accurate measurement of wood beams that are 200 to 300 years old?

Having a hard time finding accurate ways of measuring the age of wood beams in the 200-300 year old range. Any direction would be appreciated. On 2019-02-10 by Randal -

Reply by (mod) - carbon dating wood beams?

Randal,

A common but for cut lumber incomplete aging method for large wood beams should include counting growth rings.

In addition to using the wood cut markings described in the article above, look also for contextual clues such as information about the age of the structure where the beams are and / or have been used

- At RECOMMENDED ARTICLES list at the bottom of this page are six articles that can be helpful.

More sophisticated testing such as C14 (Carbon 14) testing might resolve wood age within the range of C14 dating.

I've read one opinion that you would use C14 to date individual tree rings, then count the rings in the sample and use that to calibrate an overall C14 dating that might be accurate to within 3-10 years for a 200-year-old sample of wood.

That process may need to be adjusted for human generation of radioactive dust in the atmosphere since the 1940s.

Here are some useful references on C14 dating methods

Broecker, Wallace S., and John L. Kulp. "The radiocarbon method of age determination." American Antiquity 22, no. 1 (1956): 1-11.

Collier, Donald. "New radiocarbon method for dating the past." The Biblical Archaeologist 14, no. 1 (1951): 25-28.

Kulp, J. Laurence. "The carbon 14 method of age determination." The Scientific Monthly 75, no. 5 (1952): 259-267.

Libby, Willard F., and Frederick Johnson. Radiocarbon dating. Vol. 2. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1955.

What is the value of a antique axe-cut logs in an old house?

Is there anybody out there can tell me what old axe cut logs are worth that are in Old House? On 2017-03-30 by Mike -

Reply by (mod) -

Good question, Mike.

Value will depend in part on

- the lumber dimensions

- lumber condition

- wood species (e.g. chestnut may be more valuable than oak)

- where your logs are located - since transport can be a big part of their cost or value

Shorter antique hand-hewn beams are often sold for use indoors as fireplace mantles, so not all your logs have to be long.

I looked at some antique lumber dealers to try to answer your question - they most often don't post prices so some more digging is needed.

In the U.S. I see prices running from $8 to $22 per foot depending on dimensions etc. and I see much higher prices for very attractive beams sold as fireplace mantles, even $50. per foot.

In the U.K. I've seen antique beams priced around £195.00 for a 5x5x70" member

Early timber cutting was using a double bit axe

The first timber introduced was done with a common axe, probably a double bit. It was not done with an adze - On 2016-07-27 by Anonymous -

Reply by (mod) - don't confuse broadaxe cut beams left round with bark-on with rough-hewn adze cut "squared up" beams

Thanks for your comment, Anonymous; let's be more clear: cutting timbers was done with an axe and sometimes rough-hewn timbers may have been prepared with an axe but more commonly those first hewn timbers were used as round logs, sometimes with bark-on.

Lehman (2015) agrees that the broadaxe was used for hewing timbers (cutting down trees), a broad hatchet was used for hewing smaller timbers, and "The Carpenter's Adze-used to finish levelling the surfaces of sleepers and other floor pieces."

It's possible to somewhat flatten one or more sides of a round log using an axe, or double-bit axe.

Some timbers were hewn flat on just two sides, such as in the Missouri-French houses.

Most four-sided squared timbers we'll see in older buildings in Europe, the U.K., Russia, and in North America in standing buildings were flattened using an adze or a combination of adze and axe in which the axe made straight-on cuts into the log and the adz chopped out those chips and further flattened the surface.

Interestingly the adze is not a modern tool; it dates from pre-historic times when people made an adze out of chert or other stone.

Do you agree?

Also see these

Reference citations on hewing timbers and on early use of the adz or adze:

- Balfour, S. F. "Hong Kong before the British: being a local history of the region of Hong Kong and the New Territories before the British occupation." Journal of the Hong Kong Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society (1970): 134-179.

- Garvin, James L. A building history of northern New England. UPNE, 2002.

- Lehman, Michael. "Log Cabin Construction." (2015).

This paper on the methods of log cabin construction was writtenby a student taking an archaeology class at Washington and Lee University. -coincidentally the alma mater of the Inspectapedia editor. Daniel Friedman - Liewer, Marvin. "A Nebraska Log Cabin." U. Nebraska Lincoln, Nebraska Forest Service, (2004). Describes a contemporary log cabin construction project including use of traditional hand tools.

- Johnson, C. "Missouri-French houses: Some relict features of early settlement." Pioneer America 6, no. 2 (1974): 1-11.

- Meehan, James. "Demonstrating the Use of Log House Building Tools at the New Windsor Cantonment." Bulletin of the Association for Preservation Technology 12, no. 4 (1980): 39-44.

- Sloane, Eric. A museum of early American tools. Courier Corporation, 2002. [ cc at InspectApedia offices]

- Sobon, Jack A., and Roger Schroeder. Timber Frame Construction: All about Post-and-Beam Building. Storey Publishing, 2012.

- Weisler, Marshall I. "Provenance studies of Polynesian basalt adze material: A review and suggestions for improving regional data bases." Asian Perspectives (1993): 61-83.

Give me a range of dates for circular saw-cut lumber

I found your information extremely helpful regarding saw marks giving clues to the age of wood. However, I would love for you to include a range of dates that circular saws were used in cutting lumber. On 2015-07-05 by Tamara -

Reply by (mod) -

Thanks Tamara,

See these companion articles

Question: what does the stamp HSC with a Crown on this end of framing lumber tell us?

We're in the process of single storey extension. The builders have revealed the original joists.

We're in the process of single storey extension. The builders have revealed the original joists.

One joist has this mark on it. Any idea what the lettering stands for?

We reckon our house was built around 1935.

Moderator reply: Humboldt Sawmill Company?

So sorry, I don't recognize that stamp. I thought it might refer to a kit home but the best bet is that this is a stamp from the Humbldt Sawmill Company, originally located in California.

I researched the HSC with Crown stamp and think it may refer to the Humboldt Sawmill Company, LLC (HSC).

It would be helpful to know the location of the building where this joist and stamp appear.

The name Humboldt Lumber Mill Co. appears in deeds as early as April 1883 in Humboldt County, California.

The address of the **current** HSC or Humboldt Sawmill Company - formed in 2008 - is given below. This Humbolt is a descendent of PALCO, the Pacific Lumber Company that filed for bankruptcy in 2007.

Humboldt Sawmill Company Address: 125 Main Street Scotia, CA 95565 USA

Phone: 707-764-4472 Website: https://www.GetRedwood.com

Reader Follow-up:

Oh dear Daniel I hope I haven't wasted your time. We live in Lancashire, which is in North West England. So unlikely it's come from California. Still interested to know what you think.

Moderator reply:

Not at all; I thought that "crown" looked rather royal, but, then, it's used in various countries. This is a reminder to ask the context - City and Country where a building is located.

Your joist is possibly a product of the UK lumber company, Crown Timber, recently renamed Södra Wood Ltd. after being acquired by Södra Wood Ltd. in March of 2019.

Photo source: Södra Wood Ltd., retrieved 2020/09/15 original source: https://news.cision.com/sodra/r/crown-timber-changes-name-to-sodra-wood-ltd,c2158417

Current address: Crown House, 1 Wilkinson Road

Love Lane Industrial Estate

Cirencester GL7 1WH

England, United Kingdom [Website is not functional - Ed.]

...

Continue reading at FRAMING METHODS, AGE, TYPES or select a topic from the closely-related articles below, or see the complete ARTICLE INDEX.

Or see these

Recommended Articles

- AGE of a BUILDING, HOW to DETERMINE - home

- ARCHITECTURE & BUILDING COMPONENT ID

- CROSS BRACING, HISTORY of - the St. Andrew's Cross Brace

- FRAMING AGE, SIZE, SPACING, TYPES

- FRAMING MATERIALS, AGE, TYPES

- FRAMING METHODS, AGE, TYPES

- KIT HOMES, Aladdin, Sears, Wards, Others

- LOG HOME CONSTRUCTION

- MODULAR CONSTRUCTION

- NAILS, AGE & HISTORY

- PANELIZED CONSTRUCTION

- PRE-CUT LUMBER CONSTRUCTION & LEAVITTOWN

- SAW & AXE CUTS, TOOL MARKS, AGE

- SAW BLADE SIZE CALCULATED from SAW MARKS

- SAW BLADE MARKS to SAW SIZE CALCULATION ICT

Suggested citation for this web page

SAW & AXE CUTS, TOOL MARKS, AGE at InspectApedia.com - online encyclopedia of building & environmental inspection, testing, diagnosis, repair, & problem prevention advice.

Or see this

INDEX to RELATED ARTICLES: ARTICLE INDEX to BUILDING AGE

Or use the SEARCH BOX found below to Ask a Question or Search InspectApedia

Or see

INDEX to RELATED ARTICLES: ARTICLE INDEX to BUILDING STRUCTURES

Or use the SEARCH BOX found below to Ask a Question or Search InspectApedia

Ask a Question or Search InspectApedia

Try the search box just below, or if you prefer, post a question or comment in the Comments box below and we will respond promptly.

Search the InspectApedia website

Note: appearance of your Comment below may be delayed: if your comment contains an image, photograph, web link, or text that looks to the software as if it might be a web link, your posting will appear after it has been approved by a moderator. Apologies for the delay.

Only one image can be added per comment but you can post as many comments, and therefore images, as you like.

You will not receive a notification when a response to your question has been posted.

Please bookmark this page to make it easy for you to check back for our response.

IF above you see "Comment Form is loading comments..." then COMMENT BOX - countable.ca / bawkbox.com IS NOT WORKING.

In any case you are welcome to send an email directly to us at InspectApedia.com at editor@inspectApedia.com

We'll reply to you directly. Please help us help you by noting, in your email, the URL of the InspectApedia page where you wanted to comment.

Citations & References

In addition to any citations in the article above, a full list is available on request.

- In addition to citations & references found in this article, see the research citations given at the end of the related articles found at our suggested

CONTINUE READING or RECOMMENDED ARTICLES.

- Carson, Dunlop & Associates Ltd., 120 Carlton Street Suite 407, Toronto ON M5A 4K2. Tel: (416) 964-9415 1-800-268-7070 Email: info@carsondunlop.com. Alan Carson is a past president of ASHI, the American Society of Home Inspectors.

Thanks to Alan Carson and Bob Dunlop, for permission for InspectAPedia to use text excerpts from The HOME REFERENCE BOOK - the Encyclopedia of Homes and to use illustrations from The ILLUSTRATED HOME .

Carson Dunlop Associates provides extensive home inspection education and report writing material. In gratitude we provide links to tsome Carson Dunlop Associates products and services.