Historical Research on the Production of Nails

Historical Research on the Production of Nails

Research Citations & Details of Age of Nails to Indicate Building Age

- POST a QUESTION or COMMENT about determining building age by examining its hardware

Antique & modern Nails, including wood treenails, hand-wrought nails, cut nails, wire nails, sprites, spur headed nails, etc. can tell us something about the age and history of buildings and communities.

We provide research citations and excerpts describing antique nails focusing on hand wrought nails, cut nails, and machine made nails used in wood frame construction or interior finishing or carpentry work.

We include useful dates for the manufacture of different nail types along with supporting research for various countries from Australia and the U.K. to the U.S. to New Zealand.

Page top photo: a hand wrought spike discussed in these pages.

This article series describes and illustrates antique & modern hardware: door knobs, latches, hinges, window latches, hardware, nails & screws can help determine a building's age by noting how those parts were fabricated: by hand, by machine, by later generations of machine.

InspectAPedia tolerates no conflicts of interest. We have no relationship with advertisers, products, or services discussed at this website.

- Daniel Friedman, Publisher/Editor/Author - See WHO ARE WE?

Research on History of Hand Wrought Nails, Cut Nails & Wire Nails

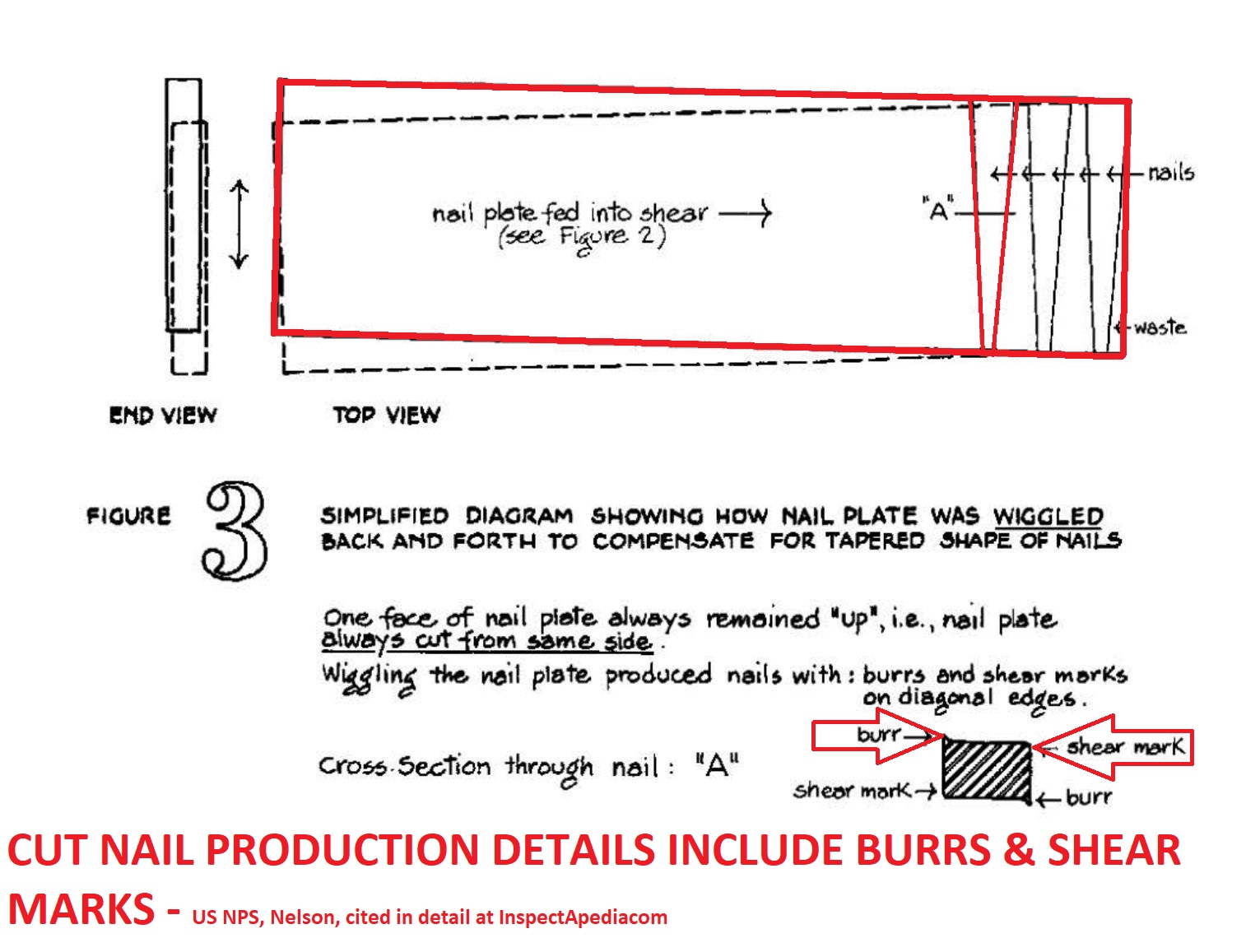

Drawing: details of cut-nail production explain why you will see shear marks and burrs on machine-cut nails or sprigs.

Drawing: details of cut-nail production explain why you will see shear marks and burrs on machine-cut nails or sprigs.

This image is adapted from the US NPS Nail Chronology article by Nelson cited in detail below. Some of these citations are from Nelson, NPS.

[Click to enlarge any image]

Below we provide research articles on the history of production of nails for various countries or parts of the world. Use the page top or bottom CONTACT link to suggest additional resources.

- NAIL AGE DETERMINATION KEY - web article

- NAIL & HARDWARE CLEAN-UP - web article

History of Nails in Australia

- Australia Nail History

- Higginbotham, Edward. "The excavation of buildings in the early township of Parramatta, New South Wales, 1790-1820s." The Australian Journal of Historical Archaeology (1987): 3-20.

Abstract:

This paper describes the excavation of a convict hut, erected in 1790 in Parramatta, together with an adjoining contemporary out-building or enclosure. It discusses the evidence for repair, and secondary occupation by free persons, one of whom is tentatively identified.

The site produced the first recognised examples of locally manufactured earthenware. The historical and archaeological evidence for pottery manufacture in New South Wales between 1790 and 1830 is contained in an appendix. - How, Christopher Ian. REVISITING EWBANK NAILS AS AIDS TO DATING CONSTRUCTION ELEMENTS [PDF] in Fabric, The Threads of COnservation, Australia ICOMOS Conference, 5-8 November 2018, Adelaide Australia, retrieved 2019/05/01 original source: http://www.aicomos.com/wp-content/uploads/Revisiting-Ewbank-Nails-full-paper.pdf

- How, Christopher, & Miles Lewis. THE EWBANK NAIL [PDF] in Proceedings of the Third International Congress on Construction History. 2009. Retrieved 2019/05/01 original source http://www.bma.arch.unige.it/PDF/CONSTRUCTION_HISTORY_2009/VOL2/HOW-chris_Paper-revised_layouted.pdf

ABSTRACT: A productive liaison between an American mill engineer and an English merchant, led to the production in Newport, Monmouthshire of one the first effective machine made nails suitable for hardwoods. It had a remarkable run of over one hundred years in use in Australia, where for a long time it was ubiquitous.

Subtle changes to the nail profile are particularly useful in establishing a series of threshold dates for various buildings constructed there during the pioneer period and hence assists in estimating their construction dates.

The “Starhead”, or “Ewbank” nail, as it was often known, was also exported to China, Chile, India, New Zealand, and other parts of the British Empire, during the latter half of the of nineteenth century , as well as being widely used within Britain.

- Higginbotham, Edward. "The excavation of buildings in the early township of Parramatta, New South Wales, 1790-1820s." The Australian Journal of Historical Archaeology (1987): 3-20.

History of Nails in India

- Chakrabarti, Dilip. "The beginning of iron in India." Antiquity 50, no. 198 (1976): 114-124.

History of Nails in New Zealand

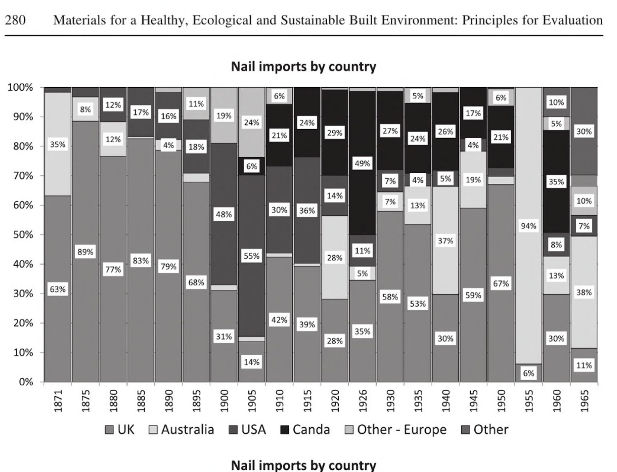

Illustration: Nigel (2017) gives the dominant countries from which nails were imported into New Zealand, 1871 - 1965. [Click to enlarge any image]

Illustration: Nigel (2017) gives the dominant countries from which nails were imported into New Zealand, 1871 - 1965. [Click to enlarge any image] - Isaacs, Nigel. NAILS IN NEW ZEALAND 1770 to 1910 [PDF] Construction History Vol. 24, 2009, retrieved 2019/05/01 original source: http://researcharchive.vuw.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/10063/1217/article.pdf?sequence=1

Abstract:

This paper reviews the earliest records of metal nails in New Zealand, and then provides a comprehensive New Zealand review from the 1840s to 1910s of nail imports, published newspapers, trade catalogues and patents.

It concludes that while there may have been a small scale hand-made nail industry, it was not until the late l880s that the first wire nails were manufactured in New Zealand and not until after 1910 that the industry became established to any extent. - Isaacs, Nigel. "Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, New Zealand." Materials for a Healthy, Ecological and Sustainable Built Environment: Principles for Evaluation (2017): 271.

Except. 12.3.5 Nails

... It could be expected that local nail manufacture would have developed early to support the extensive use of timber construction.

Although different authors have postulated the existence of an indigenous nail manufacturing industry in the mid to late 1800s (Salmond, 1989, p. 105; Cottrell, 2006, p. 429, Thomson, 2005 p. 107), the first nail machine was only imported in 1887 (Isaacs, 2009, p. 93).

Prior to 1862 no nail import statistics are available but newspaper advertisements and shipping reports provide qualitative information showing the availability from the earliest European settlement of iron bar for the local forging of nails, as well as machine-made wrought and cut nails.

In the 1860's French wire nails and American cut nails were being sold, with English wire nails being advertised in the 1870s (Isaacs, 2009, p. 85).

The last advertisement found for nail rod iron, necessary for hand forging of nails, was in 1863 (Lyttleton Times, p. 4, 19 August 1863), although this may only mean that it was so common that advertising was not reqjired.

The availability of imported nails coupled with improved transport probably made it preferable to use imported facatory-made, rather than locally hadnmade nails.

Fig. 12.4 shows over time the dominant country supoplier of nails varied widely.

... The local nail manufacturing industry became active from the 1890s and is probably in part responsible for the reduced weight of nail imports per capita.

History of Nails in Scotland

-

Glasgow Steel Nail Co., The history of NAIL MAKING, - 'Traditional Cut Nails - worth preserving? [on file as PDF], Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors (RICS), Building Conservation Journal, May 2002 retrieved 2020/07/07 original source: http://www.glasgowsteelnail.com/nailmaking.htm

Excerpt: Glasgow Steel Nail Co has been involved in many interesting projects that have included providing nails for the Globe Theatre in London, restoration work on Stirling Castle and other castles. The nails are generally used for doors, floors, gates, indeed anywhere a period nail has to be displayed.

The company is also prepared to consider special projects, for example, it produced a bronze boat nail for the building of the replica ship the 'Matthew' that in the year 2000 re-traced the 500 year old voyage of John Cabot who discovered New Foundland.

History of Nails in the U.K.

Illustration: a spur-headed flooring nail from an 1806 home in Dartmouth described by How (2014.

- A New English Nail Machine, Hardware. 7 Feb 1890. HARDWARE MERCHANDISING, Jan 3, 1890 [PDF] weekly, full year of issues, retrived 2018.06/16, original source: https://archive.org/stream/hardwaremerch1890toro#page/n4/mode/1up

Text complete:

A New English Nail Machine

A new nail machine, known as the Copewell, has been tested in London. Each machine will produce over 600 pounds of average sized nails in the working day of ten hours, and one boy can fully attend to four machines.

The nails themselves are produced from the cold steel bar, and are, therefore, even in temper throughout and uniform, whilst it is claimed for them that in their finish, tensil strength, holding power in the chuck, and freedom from liability to fracture under the heads, they are withouit rival in the market.

Their cost is but little over half that of nails made by other processes. The process itself is very simple.

The end of a coil of steel bar or wire on a drum is put into a machine, which automatically cutting pieces of the required length, passes them down through a series of dies, which draw and bevel them;

they are then caught in slots in a revolving plate and pointed, and finally dropped - finished nails ready for use - without any hand labor whatever.

Should any failure take place in any of these operations with any nail blank, the fault instantly throws the machine out of gear, whilst a danger signal marks the exact spt where it occurrs.

To remove the faulty blank and restart the machine is the matter of seconds only. - British Museum, Portable Antiquities Scheme, website: www.finds.org.uk - search for "Wire Fence Nails" or "hook top nails" tp see nails and metal fragments dating from midieval times:

fiddle head nails, wrought iron tapering spikes, T-shaped iron nails with retangular shanks, even roman sherds and iron "Fiddle keyu" horseshoe nails dating from the late 11th to 13th centuries. Retrieved 2019/09/09 original source: https://finds.org.uk/database/search/results/materialTerm/Iron/objectType/NAIL/broadperiod/MEDIEVAL/page/1

Contact:

Finds Liaison Officers The Scheme currently employs 39 Finds Liaison Officers. Matthew Fittock Finds Liaison Officer - Bedfordshire & Hertfordshire Verulamium Museum, St Michael's Street, St Albans, Hertfordshire, AL3 4SW Work T: 01727 819379 E: Matthew.Fittock@stalbans.gov.uk - Ciccone, Salvatore A., The FUNCTION of a NAIL: An Archaeological Examination of Three 18th- and 19th-Century Eastern Pequot Reservation Homes in Southeastern Connecticut [PDF] Graduate Masters Theses. 753. University of Massachusetts Boston - retrieved 2023/03/18 original source: https://scholarworks.umb.edu/masters_theses/753

Excerpt:

Because they were cut and headed cold or at a low temperature as compared to hand wrought nails, the final heading process often caused cracks which were present until advances in the iron making of the 1840s (Wells 1998: 86). - Corder, Philip. "Roman Spade-irons from Verulamium, with some notes on examples elsewhere." Archaeological Journal 100, no. 1 (1943): 224-231.

- Goist, David, HISTORICAL REVIEW OF NAILS AND TACKS [PDF] - excerpting Goist on Nails & Tacks in the conservation-wiki.com article on stretchers & strainers. Retrieved 2022/07/22, original source: www.conservation-wiki.com/wiki/Stretchers_and_Strainers:_Materials_and_Equipment#Historical_Review_of_Nails_and_Tacks

- How, Chris, Caroline Bolle, Jean-Marc Léotard, and Artur Lapins. "The Medieval bi-petal head nail." In Further Studies in the History of Construction: the Proceedings of the Third Annual Conference of the Construction History Society: The Proceedings of the Third Annual Conference of the Construction History Society, p. 119. Lulu. com, 2016.

- How, Chris. "Early Steps in Nail Industrialisation." In Studies in Construction History: the proceedings of the Second Construction History Society Conference: The Proceedings of the Second Construction History Society Conference, p. 81. Lulu. com, 2015.

- How, Chris. "The British cut clasp nail." In Proceedings of the First Conference of the Construction History Society, pp. 231-38. 2014.

Mr. How is a retired structural/heritage engineer, Australia. - Phillips, Maureen K., MECHANIC GENIUSES AND DUCKIES REDUX: NAIL MAKERS AND THEIR MACHINES, ASSOCIATION FOR PRESERVATION TECHNOLOGY [PDF] APT Bulletin: The Journal of Preservation Technology Vol. 27, No. 1/2, A Tribute to Lee H. Nelson (1996), pp. 47-56 (10 pages) Published By: Association for Preservation Technology International (APT) - retrieved 2023/03/18, original source: https://doi.org/10.2307/1504500 https://www.jstor.org/stable/1504500

- Graham, Karla, Dylan Cox, OWMBY NAILS PILOT STUDY: Owmby, Owmby by Spital, Lincolnshire [PDF] (2001) Centre for Archaeology Report 26/2001, - retrieved 2023/03/17, original source: historicengland.org.uk/research/results/reports/5008/OWMBYNAILSPILOTSTUDY_OWMBYOWMBY-BY-SPITALLINCOLNSHIRE

Nails found at a late iron age and Roman settlement. - King, P. W. THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE IRON INDUSTRY IN SOUTH STAFFORDSHIRE IN THE 17TH CENTURY: HISTORY AND MYTH [PDF] Trans. Staffs. Arch. & Hist. Soc 38 (1999): 59-76.

Excerpts:

It is first necessary on the one hand to distinguish the production of iron by ironmasters in blast furnaces and forges using water-power and on the other its manufacture into finished iron wares, such as nails, mainly by ironmongers who put out the iron they had bought from ironmasters to nailers and other workmen, working at home.

The ironmasters' principal raw materials were wood and 'mine', that is iron ore, which in South Staffordshire was argillaceous ironstone from the coal measures.

Elizabethan statutes prohibited the use of timber (defined as the trunks of trees that would square to one foot at the butt) for making iron, and timber was anyway generally too dear for such use.

What ironmasters used was cordwood, the result of cropping coppices about every 14 years, as well as the tops and lops from timber trees that were unsuitable for other purposes.

Until the mid 16th century iron had been made by direct reduction of the ore (without being melted) in 'bloomeries', known popularly as bloomsmithies or just smithies, the resultant 'bloom' (a spongy mass of iron with slag) being hammered out into a bar under water-powered hammers."

Such a 'smithy' was built at James Bridge near Walsall in 1543,7 and about 1577Sir Francis Willoughby built (or considered building) one on the Black Brook, possibly at Hints Forge, to use his wood from Middleton (Warws.),"

This process was gradually replaced, from the 1560s in the Midlands, by a two-stage (that is, an indirect) process using a blast furnace and a forge.

- Pitt, Ken, Damian M. Goodburn, Roy Stephenson , Christopher Elmers 18th- and 19th-CENTURY SHIPYARDS at the south-east entrance to the WEST INDIA DOCKS, LONDON [PDF] The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology (2003) 32. 2: 191–209doi:10.1016/j.ijna. 2003.02.001

Excerpt:

Evidence for the dock consisted of a large irregular feature dug through reclamation deposits; the onlydating evidence was a single pipe bowl dated to around 1730 to 1780.

Perpendicular to the edge of this cut was a line of three posts which may be a relict of an earlier timber structure, possibly part of Rolt’s yard of the 17th century.

Tree-ring samples were taken but could not be dated.

These posts were reused decayed oak frame elements from a large carvel built ship, pierced with shaved 38 mm diameter oak treenaails. - Salzman, Louis, Building in England (Oxford, 1952)

- Sjögren, Guy. "The rise and decline of the Birmingham cut-nail trade, c. 1811–1914." Midland History 38, no. 1 (2013): 36-57.

- Suffolk Latch Co, "History of Iron Nails" [archived here as PDF], retrieved 2020/07/06 Suffolk Latch Co., Unit B

Bridewell Works, Clare, CO10 8QD UK, Tel: 01787277277 Email: info@suffolklatchcompany.co.uk original source: https://www.suffolklatchcompany.co.uk/blogs/news/172098887-history-of-iron-nails

Excerpts:

In the UK, where many Roman villa sites have been excavated, ancient nails have been found. At the fortress of Inchtuthil in Perthshire, 875,000 nails weighing 7 tonnes were found. ... Blacksmiths heated iron ore with carbon to form a dense mass of metal, which was then placed into the shape of square rods and left to cool.

After re-heating the rod, the blacksmith would cut off a nail length and hammer all four sides of the softened end to form a sharp point.

The hot nail was then inserted into a hole in an anvil and, with four strikes of the hammer, the blacksmith would form the rose head. - Thirsk, Joan, ed. The agrarian history of England and Wales. CUP Archive, 1985.

History Of Nails in the United States

- Anonymous, "Adhesion of Nails, Spikes, and

Screws in Various Woods, Experiments on

the resistence of cut-nails, wire nails (steel),

spikes, wood-screws, lag screws," Report of the Tests of Metals and

Other Materials for industrial Purposes

made with the U.S. Testing Machine at

Watertown Arsenal, Mass., 1884 (Government Printing Office, Washington, 1886),

448-71.

- Adams, William Hampton, MACHINE CUT NAILS AND WIRE NAILS: AMERICAN PRODUCTION AND USE FOR DATING 19TH-CENTURY AND EARLY-20TH-CENTURY SITES [PDF] Hist Arch (2002) 36: 66. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03374370

Abstract: The commonly cited sources used by archaeologists for dating nails have been rendered outdated by later research. Machine cut and headed nails date from 1815 onwards, while wire nails date from 1819 onward.

Historical archaeologists need to avoid the simplistic use of invention dates and patent dates and focus instead on the mass-production dates.

There can be a significant amount of time between an invention and its first production, and even greater time until production figures are significantly high enough to affect the archaeological record.

Usually wire nails are ascribed an 1850s beginning date, but that date is both too early and too late. While some wire nails were produced in 1819, no significant quantities were produced in the United States until the mid-1880s.

Thus, we need to extend the manufacturing date back some 30 years with the caveat that the effective manufacturing date range begins in the 1880s.

By examining production figures for wire nails, a model is generated for dating sites built of machine cut nails.

This model is then examined using data from dozens of sites in the USA and Canada. Just as important, the model provides clues to recycling activity and access to different manufacturing sources.

Excerpts:

Until the late-18th century, blacksmiths working independently or at naileries wrought virtually all nails.

These nails were wrought from nail rods or from nail splits cut from a plate. Smiths hammered the red-hot iron rods into a point and then placed them in a vise, hammering down to produce a head (Fontana and Greenleaf 1962:52).

by virtue of being made individually by hand, wrought nails show considerable morphological and metric variability.

Jeremiah Wilkinson of Cumberland, Rhode Island, in 1775 devised a way of producing nails from iron plates (Fontana and Greenleaf 1962:44).

The nails were hand headed and show variability in the heads but some uniformity in the shanks. Such nails "were made from rectangular strips of iron plate and tapered to a point by a single cut across the plate.

The thickness and height of the plate determined the thickness and length of the nail" (Fontana and Greenleaf 1962:52). This kind of nail generally dates from ca. 1790 to the mid 1820s (Nelson 1968:6), although a few examples can date as early as the 1775 invention date.

More research is needed to clarify the spread of this technology and ascertain production figures.

Some of the rods for these nails were imported from England; for example, 2,307 pounds "in nail or spike rods, slit" were imported from England in 1824 (Secretary of the Treasury 1825:146-147).

Although the archaeological literature generally uses a date of ca. 1815 for the introduction of the early machine cut-and-headed nails following Lee H. Nelson (1968), later research has shown that the earliest such machines actually were in use was by 1794 near Boston.

- Aytekin, Alper, DETERMINATION OF SCREW AND NAIL WITHDRAWAL RESISTANCE OF SOME IMPORTANT WOOD SPECIES [PDF] Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2008, 9, 626-637 retrieved 2019/01/09, original source: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2635684/pdf/ijms-9-4-626.pdf

- American Plywood Association, APA, "Portland Manufacturing Company, No. 1, a series of monographs on the history of plywood manufacturing",Plywood Pioneers Association, 31 March, 1967, www.apawood.org

- Ball, Ephraim 1886 The Hand-made Nail Trade. In The Resources, Products and Industrial History of Birminsham and the Midland Hardware District, editedb y Samuel t,mmins. Robert Hardwicke, London.

- Bill, Jan, IRON NAILS in IRON AGE & MIDIEVAL SHIPBUILDING [PDF] (1994) Oxbow Monograph 40 in Crossroads in Ancient Shipbuilding, Proceedings of the Sixth International Symposium on Boat and Shipbuilding Archaeology, ISBSA 6, Crister Westerdahl (Ed.) Oxbow Books, Park End Place, Oxford Ox1 1Hn England

- Bradley Smith, H.R., "Chronological Development of Nails," supplement to Blacksmiths and Farriers' Tools, Shelburne Museum (Shelburne, Vermont, 1966)

- Business Week 1953 Nailing Down their Market: Aluminum Nails. Business Week February 21:44

- Chapin, J.R. 1860 Among the Nail-makers, Harperls New Monthly Magazine 21(122):145-164.

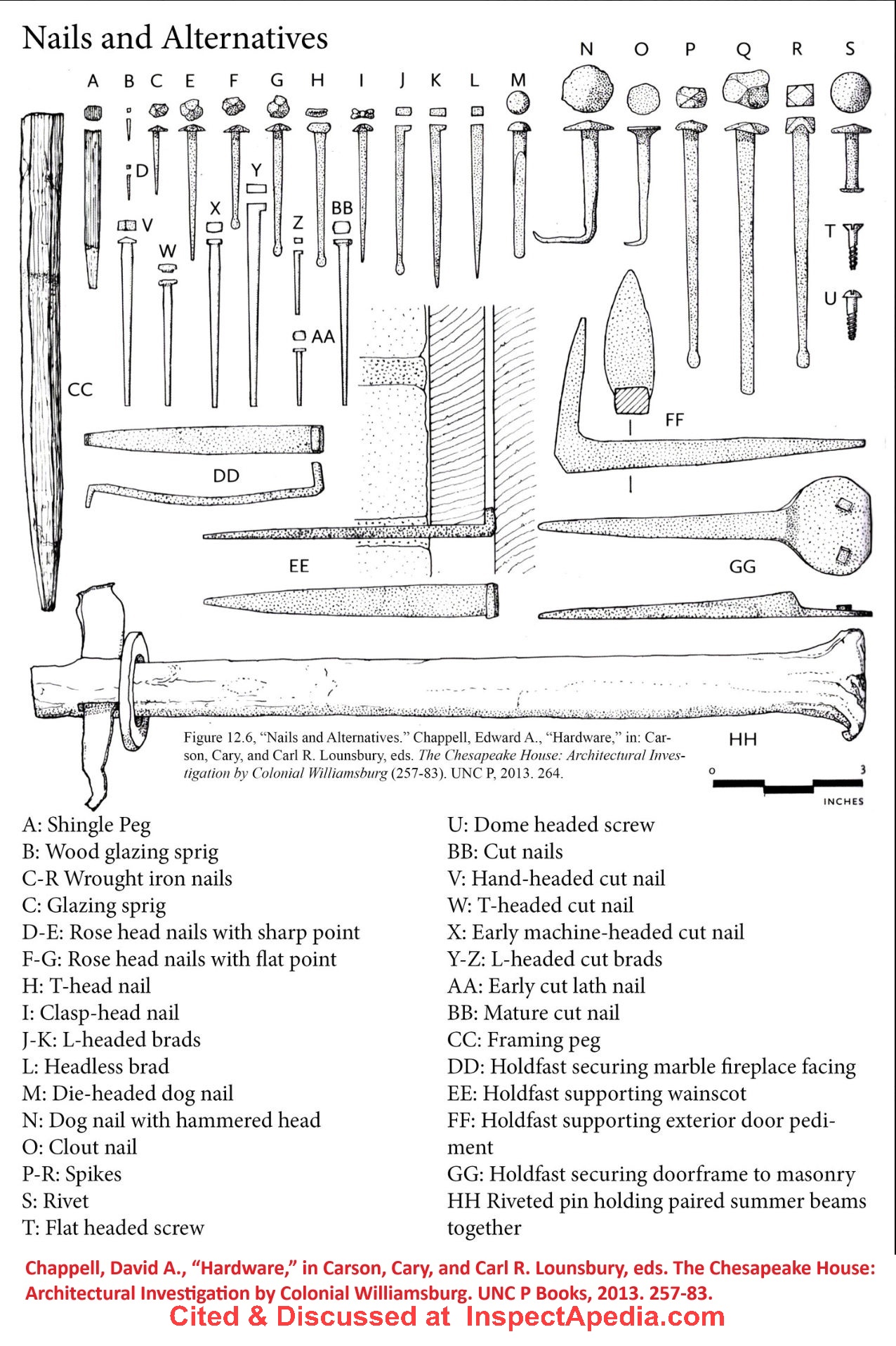

- Chappell, David A., “Hardware,” in Carson, Cary, and Carl R. Lounsbury, eds. The Chesapeake House: Architectural Investigation by Colonial Williamsburg. UNC P Books, 2013. 257-83.

This text, both Chappell's Hardware section as well as other contents are widely cited in historic preservation articles such as the Cloverfields report on historic nails used to date different sections of an historic home (cited further below), and in

Murray-Dick-Fawcett House Historic Structure Report [PDF] Glavé & Holmes Architecture for the Office of Historic Alexandria, City of Alexandria, Virginia | April 19, 2024 (REVISION 1) - copy on file as Murry-Dick-Fawcett-Report-Glave-Holmes.pdf

Illustrated below, Chappell's table of Nails and Alternatives, p. 264

- Chartier, Craig S. Samuel Fuller Homesite Report Series Volume 2 of 7 Architectural Analysis [PDF] Plymouth Archaeological Rediscovery Project (PARP) Web: www.plymoutharch.com Email: craig@plymoutharch.com - retrieved 2023/09/23, original source: plymoutharch.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/79694416-Archaeology-of-the-Samuel-Fuller-Homesite-Architecture.pdf

Excerpt:

While hand-wrought nails and spikes were produced since ancient times, by the late eighteenth century they were replaced by partially machine cut nails between 1790 and 1825, with the machine cutting the nail shanks and a human finisher applying the heads by hand.

By 1825 machines had been developed to crudely make the heads and by 1840 the heads and shanks were completely machine-made. Machine-cut nails continue to be produced until the present time. Eventually, by 1890s, round-shanked wire nails, which were first produced in the 1850s, began to dominate the nail market, replacing the machinecut nails.

The presence of hand-wrought nails in the assemblage may indicate a late eighteenth to early nineteenth century construction of the site, a hypothesis supported by the occurrence of creamware in the ceramic assemblage. - Cloverfields as of July 2019: Period Nails Help Date Different Sections of the House and The Structural Frame is Repaired [Web article + video] - July 25, 2019

- Danver, Steven (Ed.), Native Peoples of the World, an Encyclopedia of Groups, Cultures, and Contemporary Issues (3 Vols.), Routeledge, Taylor & Francis, London, 2013, 2015, ISBN 978-0-7656-8222-2

- Didsbury, J, "The French Method of Nail-Making," The Chronicle of the Early American lndustries Association, Inc., Vol. XII, No. 4 (December, 1959), 47-48.

P. 48 illustration of a nail-heading tool.

- ESOPUS MEADOWS LIGHTHOUSE ISLAND SPIKE [web article] - using historical context of surroundings to guess the purpose and age of iron nails artifacts.

- Hening, Statutes, Vol. I, 291. Cf "Burning Buildings for Nails," American Notes, Journal of the Society of Architectural Historian . Vol. IX, No. 3, 23, showing that an early Kent County, Delaware, courthouse was ordered destroyed in 1691 "to gett the nailes."

- Hughes, George W. THE PIONEER IRON INDUSTRY IN WESTERN PENNSYLVANIA [PDF] Western Pennsylvania History: 1918-2018 14, no. 3 (1931): 207-224.

- Isham, Norman, "An Example of Colonial Paneling", Norman Morrison Isham, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, Vol. 6, No. 5 (May, 1911), pp. 112-116, available by JSTOR.

- Keene, John Tracy, THE NAIL MAKING INDUSTRY in EARLY VIRGINIA [PDF] University of William & Mary, Dissertations, Theses, and Masters

Projects. Paper 1539624706.

https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-5k6z-he10 - retrieved 2022/04/28 original source: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=5045&context=etd

Abstract excerpts:

Nails are one of the least often studied of the necessities of colonial life. The production of wrought iron nails is not a complex industrial process.

Any blacksmith could produce them in limited numbers, but the industry was slow in getting established in Virginia for a number of reasons.

Most important among them was the Virginians ' predilection towards the almost exclusive production of a saleable export crop.

England supplied the bulk of Virginia's industrial imports, including nails. However, there was a small domestic nail making industry. Thomas Wyatt had a shop producing nails on the Eastern Shore as early as 1635* Smiths in Virginia’s few towns, such as the Geddys in Williamsburg, made some nails.

Some plantations had smithies equipped to produce nails, including Robert Carter's. Ironworks were being reestablished in the eighteenth century, and also contributed to the colony's limited production of nails.

The coming of the Revolution brought about a rapid realization of Virginia's excessive dependence on imports for nails and other vital commodities. Privateering and blockade running proved inadequate and unreliable methods of supply.

As a stopgap measure, the state engaged James Anderson, a Williamsburg blacksmith, to operate a nailery. This met the immediate need with some success, but did little to establish the industry on a permanent footing, as it ceased operation in 1 7 8 2.

Following the war, the British regained much of the Virginia nail market, but the coming of mechanization put Virginia in a better competitive position.

It is somewhat ironic that Thomas Jefferson, the noted exponent of the virtues of agrarianism over industrial life, was one of the first to establish a commercial nailery with imported British machinery in 1794.

His venture was not entirely successful, but it and a similar nailery, operated in conjunction with the Richmond penitentiary, were the precursors of an important nineteenth-century Virginia industry which established itself in such centers as Richmond, Wheeling and Lynchburg. - Kirby, Richard Shelton. Engineering in history. 1956. Reprint. New York: Dover Publications, 1990. 325. ISBN 0486264122

- Melchert, Ken, "The Humble Nail – A Key to Unlock the Past" [archived here as PDF] The Harp Gallery, 2495 Northern Road

Appleton, WI 54914

USA retrieved 2020/07/06 original source: https://www.harpgallery.com/library/nails.htm

Excerpts:

Archaeologists have found hand made bronze nails from as far back as 3000 BC. The Romans made many of their nails from iron, which was harder, but many ancient iron nails have rusted away since. The hand-forged nail changed little until well into the 1700's.

...

In Europe in the 1850's, steel wire was made into tiny nails known as “brads,” with only a very small widened head. These continue to be used to attach small moldings and trim. About 1880 in America and in Europe, the modern wire nail was developed. - Nelson, Lee H., FAIA, ARCHITECTURAL CHARACTER—IDENTIFYING THE VISUAL ASPECTS OF HISTORIC BUILDINGS AS AN AID TO PRESERVING THEIR CHARACTER [PDF], U.S. National Park Service, Preservation Briefs No. 17, September 1988, retrieved 2020/10/02, original source: https://www.nps.gov/tps/how-to-preserve/briefs/17-architectural-character.htm

- Nelson, Lee H., NAIL CHRONOLOGY as an AID to DATING OLD BUILDINGS [PDF], U.S. National Park Service, Technical Leaflet No. 48. retrieved 2019/01/08, original source: http://npshistory.com/publications/nail-chronology.pdf

Excerpt:

Dating old buildings from their nails is not a precise technique, but when used with discretion, it has proved generally reliable and useful, for example, in Independence Hall which has been subjected to a complex series of alterations from 1750 to the present time.

If a sufficient number of samples are taken from all parts of the building they can be a good indication that

( 1) the building was built entirely at a given time, or

( 2) the building has been subjected to additions, alterations, or simple maintenance measures.

Nails can help to define the extent of these changes. For this reason we believe it worthwhile to discuss briefly the various nail types that arc generally found in American buildings.

They are

( 1) hand-wrought nails,

( 2) cut nails, and

( 3) wire nails.

Within these major groups there is a surprising variety with subtle differences in type which enable us to use nails as dating tools with some certainty.'

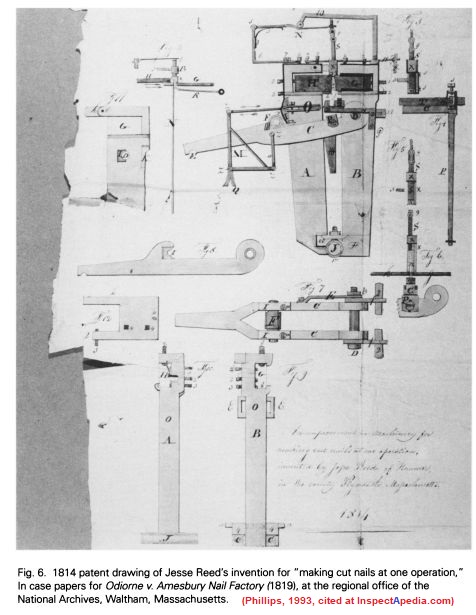

- Phillips, Maureen K., MECHANIC GENIUSES AND DUCKIES, A REVISION OF NEW ENGLAND'S CUT NAIL CHRONOLOGY BEFORE 1820, [PDF] APT Bulletin Vol. XXV No. 3-4, (1993), pp. 4-16, Association for Preservation Technology (APT) Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1504461

Excerpt from Introduction:

The standard accepted chronology of the manufacture of cut nails used in the field today is based on Henry Mercer's 1923 article "The Dating of Old Houses" and on Lee Nelson's 1968 pamplet "Nail Chronology as an Aid to Dating Old Buildings."

However, restoration work in the New England, New York, and the mid-Atlantic areas performed since the 1970's has led preservationists to theorize that some types of early cut nails may have been manufactured several years earlier than had been postulated by Mercer and Nelson.

For example, during recent restorationwork at an historic structure in Newbury, Massachusetts, cut nails with characteristics thought to date to post-1815 were found in building fabric known to date before 1807.

It was decided to test this thoery by documenting cut-nail manufacturing in New England in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

Three areas were studied: the operation of nail factories around Boston during that period, the descriptions of early nail m achines those factories used, and dateable nail samples from New England structuers that machines may have been produced.

...

A catastrophic fire in the U.S. Patent Office in Washington, D.C. in 1836 destroyed most of the specifications and drawings of the patents filed to that date. While some records were recreated from copies of patent documentation existing in other repositories, these records are far from complete, and the missing documents created critical gaps in the record.

Fortunately some of these gaps were filled when copies of specifications and drawings for two important early nineteenth-century cut nail machine patents were found filed with the ase papers of an early nineteenth-century patent inufringement lawsuits in the regional office of the National Archives in Waltham, Massachusetts.

...

In addition, documentationfor a third important early nineteenth-century machine was found in the specifications and drawings of an 1810 English patent that was filed by an American inventor.

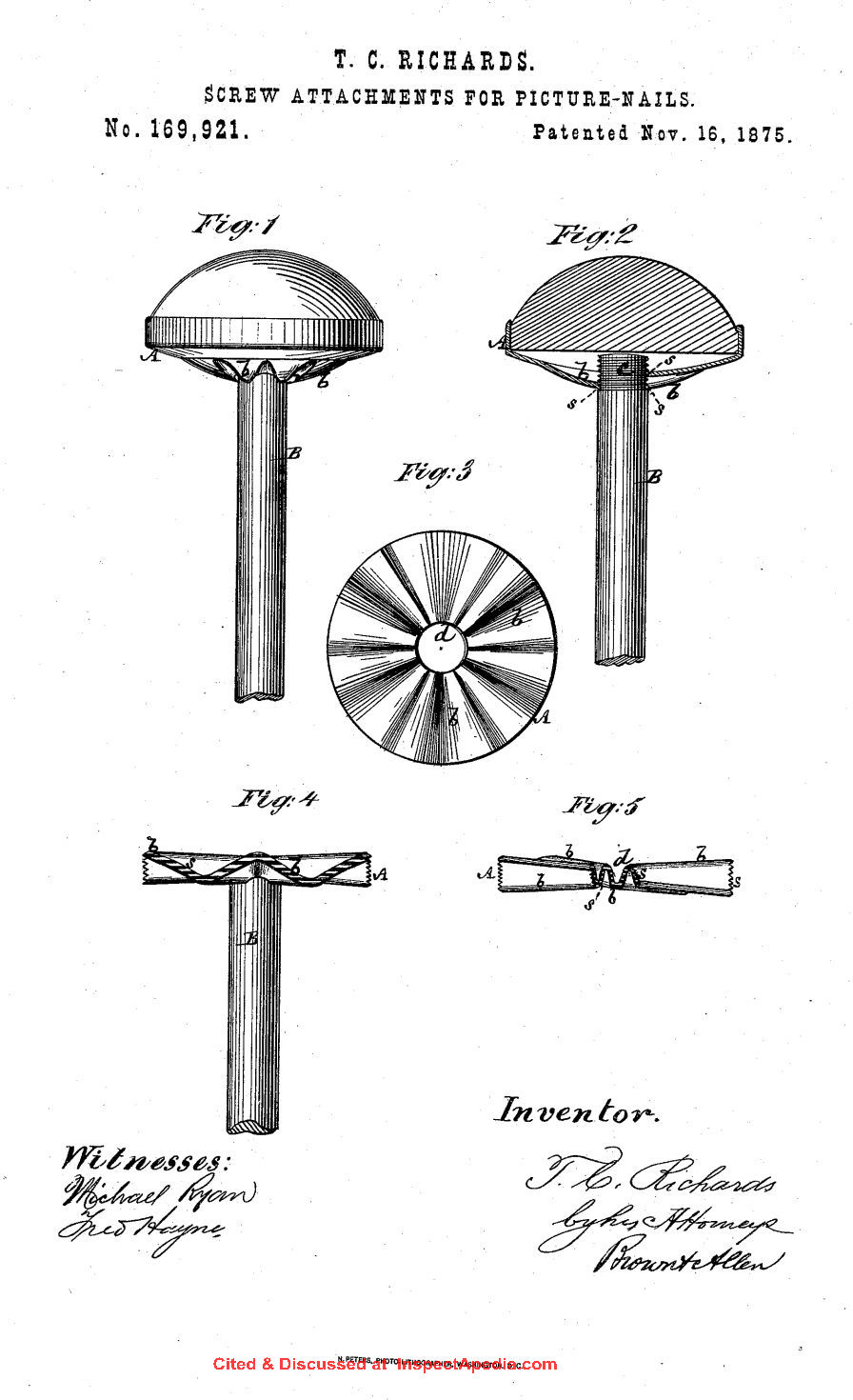

The newly-discovered material provided a tantalizing glimpse into the era of early cut-nail technology, and resulted in the development of a revised chronology for cut nails that relates specifically to New England construction for the years between 1790 and 1815. - Richards, Thomas C. "IMPROVEMENT IN SCREW ATTACHMENTS FOR PICTURE-NAILS" [PDF] U.S. Patent 169,921, issued November 16, 1875, originally retrieved on 9/23/2023 from https://patents.google.com/patent/US169921A/en.

- Ryzewski, Krysta, & Robert Gordon. HISTORICAL NAIL-MAKING TECHNIQUES REVEALED [PDF] Historical metallurgy 42, no. 1 (2008): 50-64.

Abstract

Characteristics diagnostic of manufacturing technique are retained in the microstructure of iron nails even though the original surfaces are lost in corrosion. Distinctive metal strutures differentiate hand-forged and machine-made nails.

The one-operation machines that automatically cut and headed nails left unique shear bands in the nail head metal. Presence of these shear bands indicates that nails cut and headed by machine were in use in Rhode Island before 1781.

Before about 1815 nail machines in New England operated on pre-heated iron plate, as shown by the recrystallization of the shear band.

Nails made thereafter until about 1850 were formed from cold iron and have un-recrystallized shear bands.

Cut nails made after about 1850 are in the longitudinal rather than transverse orientatin, and have a folded head struture resulting from improved design of the nail machine header grips. - Smith, Mary Margaret, Heinz W. Pyszczyk, A SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY OF HISTORICAL ARTIFACTS: c. 1760-1920 [PDF] Archaeological Survey of Alberta, 8820 - 112 Street,

Edmonton, Alberta, T6G 2P8 Canada retrievd 2019/01/09 original source: https://open.alberta.ca/dataset/ 8a3c8aab-f5f0-4a70-b9e4-456caf87253d/resource/ 4154f9e9-9ba7-4ae0-ae81-b3ee242a89ed/download/ 1988-selected-bibliography-of-historical-artifacts-c-1760-1920-manuscript-series-11-1988.pdf

P. 23-31 provided citations on nails.

- Swank, James Moore. History of the Manufacture of Iron in All Ages: And Particularly in the United States from Colonial Time to 1891. Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- Swank, James Moore. History of the Manufacture of Iron in All Ages: And Particularly in the United States for Three Hundred Years, from 1585 to 1885. Philadelphia: JM Swank, 1884.

- Tremont Nail Company, P.O. Box 31, Mansfield, MA 02048, Tel: 800-835-0121, 508-339-4500 Website: http://www.tremontnail.com/

- Tisch, Arthur S. "Modern Wood Construction, only as good as its fastening!" reprinted as Bulletin No. 1, by the American Society of Precision Nailmakers, 630 Third Avenue, New York.

- US NPS THOMAS BLANCHARD [PDF], National Park Service, U.S. Dept. of Interior, Springfield Armory, retrieved 2018/06/17, original source: https://www.nps.gov/spar/learn/historyculture/upload/Thomas-Blanchard.pdf

- Williams, David, THE IRON AGE : Vol LII : No. 22 : November 30, 1893, [PDF] original from the University of Michigan, digitized by Google. Page example shown above.

- Wells, Tom, NAIL CHRONOLOGY: THE USE OF TECHNOLOGICALLY DERIVED FEATURES [PDF], Historical Archaeology, Vol. 32, No. 2 (1998), pp. 78-99, retrieved 2019/01/08, original source (stable URL) http://www.jstor.org/stable/25616605 .

Note: Society for Historical Archaeology is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Historical Archaeology.

Abstract: A technology-based nail chronology is presented. This chronology is derived from a typology based on a combination of general information about the historical developments of the technology applied by the nail manu facturing industry and the periods of actual use for each of twelve basic nail types presently identified as having been used in Louisiana.

The author believes that the approach used to establish the Louisiana Nail Chronology can also be used to establish accurate nail chronologies in other regions.

History of Nails in Wales, U.K.

Photo above: a 6+ inch iron spike provided by InspectApedia.com reader CR, found in Wales. [Click to enlarge any image]

More photos of this Welsh iron spike are at NAILS & HARDWARE, AGE FAQs

- King, Peter. "The production and consumption of bar iron in early modern England and Wales." The Economic History Review 58, no. 1 (2005): 1-33.

Abstract:

The production and consumption of bar iron in early modern England and Wales. An estimate made of the bar iron production in England shows two periods when production grew rapidly, 1540‐1620 and 1785‐1810.

Both of these were related to the adoption of new technology‐the finery forge in the first case, and potting and stamping and then puddling in the second.

Imports of iron from Spain declined sharply after 1540, but those from Sweden became significant from the mid‐seventeenth century, and those from Russia after 1730.

Consumption grew rapidly in the late sixteenth century, and again during the eighteenth. Hence, the industrial revolution was the culmination of a long period of growth. - Nayling, Nigel, & Toby Jones. "44. THREE-DIMENSIONAL RECORDING AND HULL FORM MODELLING OF THE NEWPORT (WALES) MEDIEVAL SHIP [PDF] BETWEEN CONTINENTS Proceedings of the Twelfth Symposium on Boat and Ship Archaeology Istanbul 2009 ISBSA 12 Edited by Nergis Günsenin © 2012 Ege Yayınları ISBN No: 978-605-4701-02-5 (2009).

- Thirsk, Joan, ed. The agrarian history of England and Wales. CUP Archive, 1985.

- INVERNESS CANAL IRON TOOLS & SPIKES [web article] - discussion of iron artifacts found in the Inverness Canal, northern Scotland.

- See also the research citations at

NAILS in BARTER & TRADE

...

Continue reading at NAIL AGE DETERMINATION KEY questions & answers, or select a topic from the closely-related articles below, or see the complete ARTICLE INDEX.

Or see these

Recommended Articles

- AGE of a BUILDING, HOW to DETERMINE - home

- DOOR HARDWARE AGE

- NAILS, AGE & HISTORY - home

- HORSESHOE & HORSESHOE NAIL AGE

- NAIL & HARDWARE, AGE RESEARCH

- NAIL & HARDWARE CLEAN-UP

- NAIL AGE DETERMINATION KEY - use this key to guess at the age of your nail or spike

- NAIL ID & AGE: CUT NAILS

- NAIL ID & AGE: HAND FORGED NAILS

- NAILS in BARTER & TRADE

- NAIL SPLITS & CRACKS vs AGE

- NAIL TYPE, ANTIQUE, IDENTIFICATION KEY

- RAILROAD SPIKES

- RAILROAD SPIKE AGE - CONTEXTUAL CLUES

- SAW & AXE CUTS, TOOL MARKS, AGE

- WINDOW HARDWARE AGE

Suggested citation for this web page

NAILS & HARDWARE, AGE RESEARCH at InspectApedia.com - online encyclopedia of building & environmental inspection, testing, diagnosis, repair, & problem prevention advice.

Or see this

INDEX to RELATED ARTICLES: ARTICLE INDEX to BUILDING AGE

Or use the SEARCH BOX found below to Ask a Question or Search InspectApedia

Ask a Question or Search InspectApedia

Try the search box just below, or if you prefer, post a question or comment in the Comments box below and we will respond promptly.

Search the InspectApedia website

Note: appearance of your Comment below may be delayed: if your comment contains an image, photograph, web link, or text that looks to the software as if it might be a web link, your posting will appear after it has been approved by a moderator. Apologies for the delay.

Only one image can be added per comment but you can post as many comments, and therefore images, as you like.

You will not receive a notification when a response to your question has been posted.

Please bookmark this page to make it easy for you to check back for our response.

IF above you see "Comment Form is loading comments..." then COMMENT BOX - countable.ca / bawkbox.com IS NOT WORKING.

In any case you are welcome to send an email directly to us at InspectApedia.com at editor@inspectApedia.com

We'll reply to you directly. Please help us help you by noting, in your email, the URL of the InspectApedia page where you wanted to comment.

Citations & References

In addition to any citations in the article above, a full list is available on request.

- In addition to citations & references found in this article, see the research citations given at the end of the related articles found at our suggested

CONTINUE READING or RECOMMENDED ARTICLES.

- Carson, Dunlop & Associates Ltd., 120 Carlton Street Suite 407, Toronto ON M5A 4K2. Tel: (416) 964-9415 1-800-268-7070 Email: info@carsondunlop.com. Alan Carson is a past president of ASHI, the American Society of Home Inspectors.

Thanks to Alan Carson and Bob Dunlop, for permission for InspectAPedia to use text excerpts from The HOME REFERENCE BOOK - the Encyclopedia of Homes and to use illustrations from The ILLUSTRATED HOME .

Carson Dunlop Associates provides extensive home inspection education and report writing material. In gratitude we provide links to tsome Carson Dunlop Associates products and services.