How to Test Well Flow Rate & Water Quantity

How to Test Well Flow Rate & Water Quantity

- POST a QUESTION or COMMENT about how to test well flow, well yield, or well water quantity delivery

This article describes how a home owner or home buyer can test, measure, or estimate the amount of water available from a well and how to evaluate the water pressure delivered in a building served by a private well.

InspectAPedia tolerates no conflicts of interest. We have no relationship with advertisers, products, or services discussed at this website.

- Daniel Friedman, Publisher/Editor/Author - See WHO ARE WE?

How to Do Your Own Amateur Well Flow Rate/Well Yield Test or Well Drawdown Test

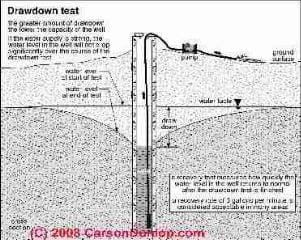

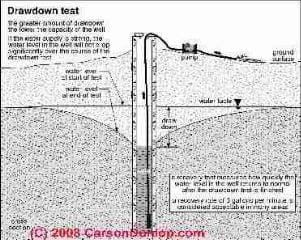

The sketch at page top, courtesy of Carson Dunlop Associates, outlines what happens during a true well flow test, also called a well drawdown or well flow test procedure. That procedure can give an accurate picture of how much water the well can deliver, though the quantity may vary seasonally or for other reasons.

The sketch at page top, courtesy of Carson Dunlop Associates, outlines what happens during a true well flow test, also called a well drawdown or well flow test procedure. That procedure can give an accurate picture of how much water the well can deliver, though the quantity may vary seasonally or for other reasons.

But there are some steps that an amateur can take first to check on the well water quantity. In fact it's possible use mere visual inspection to form a reasonable suspicion that a building has insufficient well water before testing anything.

We describe these procedures here.

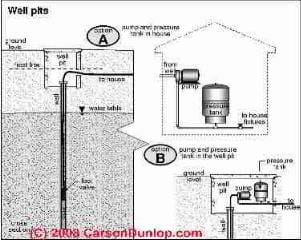

[Click to enlarge any image] Just above: schematic of a typical well pit design, also courtesy of Carson Dunlop Associates, a Toronto home inspection, education & report writing tool company [ carsondunlop.com ].

What is a true well flow rate or capacity test?

At WELL FLOW RATE we explained that a real well flow rate test is usually performed right at the well by the well driller or a plumber, at the time the well was drilled, and using special equipment.

A true well flow test, well recovery test, or well draw-down test requires special equipment and locating, opening, and pumping right at the well. That procedure has the advantage that the well flow rate recorded is not affected by other problems such as a piping error or clogged water pipes or a defective well pump or water pressure tank.

A rough "do-it-yourself" well flow test

But when buying a property it's reasonable to perform your own crude water flow test right in the building, so long as you keep in mind that the water pump, water tank, pump controls, and the condition of the water supply piping, the height of the building, and the condition of the fixtures (such as a clogged sink spigot strainer) are all affecting the actual flow rate you see at a fixture.

What we describe below is not a true well flow test or well drawdown test but this procedure can let us know early if there is an obvious red flag alert about water quantity.

How Water Flow & Pressure Behave in a Building

The water flow rate at a building served by a pump and well will vary over time

as the pump cycles on and off, and perhaps slow down or even stop completely if the well and its static head have only a limited volume of water available.

The water pressure at a fixture served by a private well, pump, and pressure tank, will normally vary between the pump cut-in pressure (typically 20 psi or 30 psi) and the pump cut out pressure (typically 40 psi to 50 psi or a little higher).

If water pressure is always "ok" but varies between pretty strong and not so strong

this might be normal.

Because the water pressure normally varies within this range, you may observe a modest change in water flow at an individual fixture such as a shower head or sink faucet.

If water pressure starts very strong and falls off to much slower immediately,

we suspect a problem with clogged piping in the building: if the inside of a water supply pipe is blocked by mineral deposits or rust the effective diameter of the pipe is reduced, causing a reduction in water flow rate in a building even if the starting water pressure is good.

Lots of people are confused about the difference between water flow rate (how many gallons per minute are coming out of a faucet) and water pressure (how hard is the water pressing inside the pipes and fixtures).

If water pressure drops way down to a very slow rate or stops entirely,

there is a problem with the water pump, tank, piping, pump controls, or worst, there may be a problem with the well itself.

We explain how to diagnose loss of water pressure in detail

at WATER PRESSURE LOSS .

What is a Reasonable Water Flow Rate in a Building?

Subjectively, we should be able to go to the highest bathroom or other plumbing facility in the building and run two fixtures simultaneously, seeing a reasonable water flow in which one could shower or wash. If you turn on the top floor shower and then open a sink faucet and you see the shower slow to a trickle, the building water pressure is unacceptable.

If you couldn't reasonably bathe in a trickling shower flow, the flow is not functional. T

his usually not a water quantity problem, it's a pump, water tank, piping, or fixture problem. Usually. A well with a bad flow rate can also show up as a poor in-building water flow rate.

A typical bath sink faucet will flow around 1 gpm to 2 gpm, bath tub spout will flow at around 2.5 to 5 gpm, and a kitchen sink faucet at around 2-3 gpm. Low-flow water-saving fixtures may provide a good strong water stream but fewer gallons per minute.

See details at

- DEFINITION of REQUIRED WATER WELL YIELD or Flow Rate functional use or to obtain a mortgage

- DEFINITION of SAFE WATER WELL YIELD

Step by Step Guide to a Simple Well Yield Test that a Home Buyer or Home Owner can Perform?

Provided the home, community, and season are not in a time or area of drought and water shortage, it is reasonable to "waste" some well water for the benefit of the chance of discovery of a very important and costly water shortage at the individual well being tested.

In some cases this test may be inappropriate (drought, already-failed septic field) or the owner may not permit it to be performed. If you cannot test water quantity or well yield you should not assume that you will have enough water at the property until you know more.

- Turn on water at one or more plumbing fixtures.

- Measure or estimate the flow at each fixture being run.

- Observe the well pump controls at the water tank:

is the pump running continuously? If so we're continuously taking water out of the well;

If not, we're taking water out of the well intermittently which we can continue to do but it's a less aggressive test and any calculations of total amount of water run will be inaccurate as a maximum well yield number.

Record whether the pump was running continuously or not. - Track the number of minutes that each plumbing fixture is run

- If available, obtain specifications on the well so that later we can calculate the volume of water in the static head in the well. Static head and its significance when testing well yield are explained

at WELL FLOW RATE - Run an estimated 150 to 300 gallons of water or at a bare minimum, 50 gallons per bedroom. More water can be run if there is no risk of flooding a septic system (if the building is connected to a municipal sewer)

- At the end of the test interval, record the results

- If the well and water supply system ran out of water calculate the number of gallons obtained before the well ran dry. (Details on how to do this are just below).

- If water pressure deteriorated or slowed significantly, record the time that this occurred; your volume calculations of water quantity taken out of the well after this point will be wrong and will over-state the well yield unless you re-estimate or re-measure the flow at each fixture.

- If the well and water supply system did not run out of water and if it did not noticeably slow down, calculate and record the total number of gallons of water obtained for comparison with acceptable water volumes. We show typical daily water usage volumes for residential properties

at WATER USAGE TABLE

- Evaluate the results of your water test (see notes just below).

If you can run water in the building for a reasonable period of time at a reasonable flow rate,

you can guess that you have a functional water supply system even though you don't really know how good the well is. (You could have a huge static head and a poor well recovery rate, for example, and you can't see that in the building without more investigation.)

If we can run 150 - 300 gallons of water

out of a well during the few hours of a property inspection without running out of water, the water supply system is probably functional. Some authorities give a figure of 500 gallons of water as average daily usage for a family of four.

Remember that water is not consumed uniformly over the day - it is usually consumed in two surges, in the morning and in the evening.

If we try to run too much water,

say 600 gallons or 1000 gallons of water or more during an amateur test, (if that's even possible) we're probably exceeding the design parameters of the system.

And we might flood the septic field if there is one. Such tests are unreasonable unless we know more about the well system and its purported water yield.

If water pressure and flow fell off during our test but water continued to run

then we were probably running off of the actual well yield rate or well flow rate after that point of pressure/flow change.

By noting the time that the flow rate/pressure changed, we can make a rough calculation of the static head in the well (only rough), and we can make a rough calculation of the well flow rate after we had drawn down the static head in the well.

Example of Detailed Well Flow Test/ Yield Test Procedure

- NC WELL TEST STANDARDS FOR WELL YIELD [PDF] North Carolina NC 15A NCAC 02C .0110

Excerpted below:

(a) Every domestic well shall be tested for capacity by one of the following methods:

(1) Pump Method

(A) select a permanent measuring point, such as the top of the casing;

(B) measure and record the static water level below or above the measuring point prior to

starting the pump;

(C) measure and record the discharge rate at intervals of 10 minutes or less;

(D) measure and record water levels using a steel or electric tape at intervals of 10 minutes or less;

(E) continue the test for a period of at least one hour; and

(F) make measurements within an accuracy of plus or minus one inch.

(2) Bailer Method

(A) select a permanent measuring point, such as the top of the casing;

(B) measure and record the static water level below or above the measuring point prior to starting the bailing procedure;

(C) bail the water out of the well for a period of one hour or longer;

(D) determine and record the bailing rate in gallons per minute at the end of the bailing period; and

(E) measure and record the water level after stopping bailing process.

(3) Air Rotary Drill Method

(A) measure and record the amount of water being injected into the well during drilling operations;

(B) measure and record the discharge rate in gallons per minute at intervals of one hour or less during drilling operations;

(C) after completion of the drilling, continue to blow the water out of the well for 30 minutes or longer and measure and record the discharge rate in gallons per minute at intervals of 10 minutes orless during the period; and

(D) measure and record the water level after discharge ceases.

(4) Air Lift Method.

Measurements shall be made through a pipe placed in the well. The pipe shall have an inside diameter of at least five-tenths of an inch or greater and shall extend from top of the well head to a point inside the well that is below the bottom of the air line.

(A) Measure and record the static water level prior to starting the air compressor;

(B) Measure and record the discharge rate at intervals of 10 minutes or less;

(C) Measure and record the pumping level using a steel or electric tape at intervals of 10 minutes or less; and

(D) Continue the test for a period of one hour or longer

How to Calculate Well Yield if We Run Out of Water During a Simple Flow Test

Calculate how many gallons of water you ran by adding up the individual fixture flow rates in gpm; multiply each fixture flow rate by the time it was running, and add up these numbers to get the total water volume we withdrew from the well.

Example of an amateur well yield test running three fixtures in a building:

- Fixture #1-bath sink: ran at 1 gpm for 32 minutes before water ran out; F1: 1 x 32 = 32 gallons

- Fixture #2-bathtub: ran at 2 gpm for 25 minutes before the water ran out; F2: 2 x 25 = 50 gallons

- Fixture #3-kitchen sink: ran at 1.5 gpm for 20 minutes before the water ran out. F3: 1.5 x 20 = 15 gallons.

Adding these up: Total Gallons of Water We Ran: 32+50+15 = 97 gallons total. Not much.

If our water supply system stopped dead with no water at the fixtures at the end of this test (we promptly turned everything off, including the pump when the water stopped flowing), our well gave us a total of 97 gallons before we ran dry.

If the well runs dry during modest use there is a problem:

Even though this test is messy, if we run out of water we've got a clear, unambiguous result.

We don't know how much of that 97 gallons was in the well's static head but we do know that unless we identify some other unusual problem (a broken pipe in the well or a failure of the pump itself) the well is inadequate.

If this seat-of-the-pants well yield test runs out of water, there is a problem and you'll need to call in a plumber and perhaps a well expert to diagnose the problem before you know what steps need to be taken.

Watch out: if the water stops flowing, turn off the pump so it is not damaged by running dry and hot. See how long it takes for the well to recover enough for water to flow again when the pump is turned back on by trying it every half hour or so.

What to do Next if You Suspect Inadequate Water Pressure or Water Quantity

- If water pressure was poor at one or all plumbing fixtures, call an experienced plumber to help diagnose the cause of bad water pressure.

Good water pressure in some locations and poor water pressure at others is likely to be a piping or equipment problem.

IF all of the building water pipes are mineral-clogged, significant costs may be involved in re-piping and in providing water treatment to prevent future clogs. But before you call a plumber to look at bad water pressure at sink faucets, check to see if the faucet strainers are clogged.

SeeWATER PRESSURE LOSS for a diagnostic guide. - If you ran out of water early during your well flow test, call an experienced plumber or well expert to diagnose the cause of insufficient water quantity.

Don't assume you have to drill a new well before careful diagnosis has been completed.

Significant costs could be involved, but first let's rule out an in-well piping leak or a pump defect. take a look

at WELL YIELD IMPROVEMENT.

How do We Conduct an Accurate, True Well Flow Test, Well Yield Test, or Well Drawdown Test?

As our this Carson Dunlop Associates sketch shows, a true well flow test, also called a well yield test or a well draw down test, is performed at the well, using a special pump which draws water directly from the well.

As our this Carson Dunlop Associates sketch shows, a true well flow test, also called a well yield test or a well draw down test, is performed at the well, using a special pump which draws water directly from the well.

The inspector can vary the rate at which the pump draws water out of the well in order to determine the rate at which the well can deliver a sustained water flow rate or quantity over a measured time period, usually several hours, typically 3 hours or 4 hours, and in some cases over 24 hours.

A true well flow test or well draw down test will discover the ability of the well to deliver water, without confusion caused by the characteristics of the building's own well pump, pump control, water pressure tank, water piping, or fixtures.

All of these in-building components can dramatically affect water pressure and water flow rate in the building, and the size of the static head in a well can cause confusion between how much water is "available" at any given time and how much water the well can really deliver.

We explain these factors and other reasons why the true well yield number is complex

at WELL FLOW RATE

Because a true well flow test or well water draw down test requires that a special pump be attached directly to the well, this test is not normally performed during a pre-purchase home inspection.

But this test should absolutely be performed if the inspection, building history, or other VISUAL CLUES of WELL PROBLEMS suggest that there may be a water quantity problem at the property.

Visual Clues Can Suggest that the Water Well Has Limited Capacity

Look around for other clues about water quantity: if you see lots of bottles of water stored near the water pump or water tank or even elsewhere in the building, if you see that flow restrictors are in use at every fixture, if you see a one line jet pump, any of these might be a clue that the well is unreliable or of limited capacity. Look for:

- Collections of water bottles stored by the water pump, presumably to re-prime the pump when water pressure is lost

- Large family of occupants including small children, with no dishwasher or no clothes washer installed

- Seller or realtor requests early termination of a well flow test or septic loading and dye test

- Presence of old abandoned pumps, pump parts, etc.

- Suggestions to rely on amateur or un-documented "well flow" tests that may not have been properly performed

Why is simple measurement water flow at a faucet an inaccurate test of well yield?

What about testing water flow and pressure from a well by using a flow gauge attached to a faucet? This is a "for show" measurement, not a real one - it is simply very inaccurate.

We can pretend to "measure" water flow, say at a tub spout, simply by seeing how many minutes it takes to fill the 5-gallon bucket. We can also pretend to "measure" water flow by attaching a flow meter gauge to a building faucet, typically to an outdoor spigot.

These tests are interesting but they're just pretending to measure the well - they're not really looking at the capacity of the well to deliver water. Instead this approach is really checking the capacity of the pump and piping to deliver a particular water flow rate and pressure

Lots of people do it, but we do not like nor trust most quantitative measurements of water flow at building fixtures

because giving any quantitative number to such a flow is inaccurate. The flow at a plumbing fixture is set by the fixture itself, strainer, faucet, pipe diameter, pipe clogs, and by building piping and pump and water tank.

Furthermore, while we're running fixtures at a modest rate, the water pressure will cycle up and down between the pump cut-in and pump cut-out pressure.

Since the actual water pressure is varying constantly, collecting and measuring the volume of water at a fixture during any short interval does not describe the full capability of the water supply system.

If the pump is not on we're not taking water out of the well:

If water is being run slowly in a building, or perhaps just at one modest-flow fixture, the well pump will "catch up" with the demand, pressurize the water pressure tank, and the pump will turn off.

The air spring in the water pressure tank keeps the water flowing out of the tank, but we're not taking any water out of the well during this part of the pump cycle.

When multiple building fixtures are running

and we're taking lots of water out of the system, the well pump will usually run continuously.

IF the well pump is running continuously,

AND if it is not changing the pressure in the water pressure tank,

THEN all of the pump output is going to the building fixtures and the sum of flow at all of them is probably a reasonable guess at the flow-rate capacity of the water supply system - that is, the capability of the well pump to send up water.

We're still not checking the real capability of the well to deliver water - not until we connect a pump that is capable of pulling water out of the well faster than it flows into the well.

So we're not always testing the well yield when we're running the water - it depends on how fast we run the water and how long we run the water to determine if our test has even a slight chance of telling us about the actual well yield or well flow rate.

Flow Rate At a Fixture = (Time to fill the 5-gallon bucket in minutes) / 5 gallons

But faucet water flow rate is not the well flow rate - it's the flow rate of the pump and piping in the building. Don't let anyone fool you on this point. Even if we ran all building fixtures at once, kept the well pump running continuously, and measured all of the flows (to add them up) we still are only measuring what the pump is delivering, not how much water the well can provide.

Why do these pretend tests then? Because we might run out of water early - showing that there is indeed a well capacity or water quantity problem.

Not one of these measurements accurately describes how much water is available at the well. All we're seeing is whether or not the water system is producing functional pressure and flow rate; we're not seeing how much water is in the well.

So what can a home buyer or home owner do to estimate well yield before going to the cost and trouble of hiring a well-testing company for a true well draw down test or well recovery test?

...

Continue reading at WATER QUANTITY IMPROVEMENT or select a topic from the closely-related articles below, or see the complete ARTICLE INDEX.

Or see WELL FLOW TEST PROCEDURE FAQs - questions & answers posted originally at this page

Or see these

Recommended Articles

- DEPTH of a WELL, HOW TO MEASURE

- WATER FLOW RATE CALCULATE or MEASURE - how much water is delivered at a plumbing fixture

- WATER PRESSURE MEASUREMENT

- WATER PRESSURE MEASUREMENT - water pressure in the system, dynamic & static

- WATER PUMP CAPACITIES TYPES RATES GPM

- WATER PUMP DRAWDOWN VOLUME & TIME

- WATER QUANTITY IMPROVEMENT

- WELL CLEANING & RESTORATION by GLYCOLIC ACID

- WELL FLOW RATE - how much water can the well deliver

- WELL DYNAMIC HEAD & STATIC HEAD DEFINITION - how much water is in the well

- WELL FLOW TEST PROCEDURE - valid vs. questionable

- WELL FLOW TEST for WATER QUANTITY - how to test the well

- WELL LIFE EXPECTANCY

- WELL PIPING TAIL PIECE

- WELL YIELD DEFINITION - required well yield & safe well yield

- WELL YIELD IMPROVEMENT - get more water

- WELL YIELD, SAFE LIMITS

- WELL WATER PRESSURE DIAGNOSIS

- WELLS CISTERNS & SPRINGS - home

Suggested citation for this web page

WELL FLOW TEST for WATER QUANTITY at InspectApedia.com - online encyclopedia of building & environmental inspection, testing, diagnosis, repair, & problem prevention advice.

Or see this

INDEX to RELATED ARTICLES: ARTICLE INDEX to WATER SUPPLY, PUMPS TANKS WELLS

Or use the SEARCH BOX found below to Ask a Question or Search InspectApedia

Ask a Question or Search InspectApedia

Try the search box just below, or if you prefer, post a question or comment in the Comments box below and we will respond promptly.

Search the InspectApedia website

Note: appearance of your Comment below may be delayed: if your comment contains an image, photograph, web link, or text that looks to the software as if it might be a web link, your posting will appear after it has been approved by a moderator. Apologies for the delay.

Only one image can be added per comment but you can post as many comments, and therefore images, as you like.

You will not receive a notification when a response to your question has been posted.

Please bookmark this page to make it easy for you to check back for our response.

IF above you see "Comment Form is loading comments..." then COMMENT BOX - countable.ca / bawkbox.com IS NOT WORKING.

In any case you are welcome to send an email directly to us at InspectApedia.com at editor@inspectApedia.com

We'll reply to you directly. Please help us help you by noting, in your email, the URL of the InspectApedia page where you wanted to comment.

Citations & References

In addition to any citations in the article above, a full list is available on request.

- Mark Cramer Inspection Services Mark Cramer, Tampa Florida, Mr. Cramer is a past president of ASHI, the American Society of Home Inspectors and is a Florida home inspector and home inspection educator. Mr. Cramer serves on the ASHI Home Inspection Standards. Contact Mark Cramer at: 727-595-4211 mark@BestTampaInspector.com

- John Cranor [Website: /www.house-whisperer.com ] is an ASHI member and a home inspector (The House Whisperer) is located in Glen Allen, VA 23060. He is also a contributor to InspectApedia.com in several technical areas such as plumbing and appliances (dryer vents). Contact Mr. Cranor at 804-873-8534 or by Email: johncranor@verizon.net

- Life Expectancy of Wells & Water Tanks how long should a water well and its components last?

- Flexcon, SMART TANK INSTALLATION INSTRUCTIONS [PDF], Flexcon Industries, 300 Pond St., Randolph MA 02368, www.flexconind.com, Tel: 800-527-0030 - web search 07/24/2010, original source: http://www.flexconind.com/pdf/st_install.pdf

- Grove Electric, Typical Shallow Well One Line Jet Pump Installation [PDF], Grove Electric, G&G Electric & Plumbing, 1900 NE 78th St., Suite 101, Vancouver WA 98665 www.grovelectric.com - web search -7/15/2010 original source: http://www.groverelectric.com/howto/38_Typical%20Jet%20Pump%20Installation.pdf

- Grove Electric, Typical Deep Well Two Line Jet Pump Installation [PDF], Grove Electric, G&G Electric & Plumbing, 1900 NE 78th St., Suite 101, Vancouver WA 98665 www.grovelectric.com - web search -7/15/2010 original source: http://www.groverelectric.com/howto/38_Typical%20Jet%20Pump%20Installation.pdf

- Our recommended books about building & mechanical systems design, inspection, problem diagnosis, and repair, and about indoor environment and IAQ testing, diagnosis, and cleanup are at the InspectAPedia Bookstore. Also see our Book Reviews - InspectAPedia.

- In addition to citations & references found in this article, see the research citations given at the end of the related articles found at our suggested

CONTINUE READING or RECOMMENDED ARTICLES.

- Carson, Dunlop & Associates Ltd., 120 Carlton Street Suite 407, Toronto ON M5A 4K2. Tel: (416) 964-9415 1-800-268-7070 Email: info@carsondunlop.com. Alan Carson is a past president of ASHI, the American Society of Home Inspectors.

Thanks to Alan Carson and Bob Dunlop, for permission for InspectAPedia to use text excerpts from The HOME REFERENCE BOOK - the Encyclopedia of Homes and to use illustrations from The ILLUSTRATED HOME .

Carson Dunlop Associates provides extensive home inspection education and report writing material. In gratitude we provide links to tsome Carson Dunlop Associates products and services.