Foundation movement: how to detect & diagnose active or ongoing movement in a building foundation

Foundation movement: how to detect & diagnose active or ongoing movement in a building foundation

Foundation crack age & probable cause diagnosis

- POST a QUESTION or COMMENT on how to determine if foundtation movement or damage is active and ongoing

How to determine active vs. old building foundation or structural movement:

This article explains the difference between active & static foundation movement: how to detect & diagnose active movement or movement cracks in a building foundation.

This article series describes how to recognize and diagnose various types of foundation failure or damage, such as foundation cracks, masonry foundation crack patterns, and moving, leaning, bulging, or bowing building foundation walls.

Types of foundation cracks, crack patterns, differences in the meaning of cracks in different foundation materials, site conditions, building history, and other evidence of building movement and damage are described to assist in recognizing foundation defects and to help the inspector separate cosmetic or low-risk conditions from those likely to be important and potentially costly to repair.

InspectAPedia tolerates no conflicts of interest. We have no relationship with advertisers, products, or services discussed at this website.

- Daniel Friedman, Publisher/Editor/Author - See WHO ARE WE?

MOVEMENT ACTIVE/STATIC - Foundation Movement: Determining Active or Dynamic (ongoing movement) vs. Static (no ongoing movement)

The photo at the top of this page shows a bowed masonry block foundation wall with horizontal cracking that occurred due to earth loading at the time

of construction, probably by vehicles driving too close to the foundation wall shortly after it was constructed.

The photo at the top of this page shows a bowed masonry block foundation wall with horizontal cracking that occurred due to earth loading at the time

of construction, probably by vehicles driving too close to the foundation wall shortly after it was constructed.

At this website we explain how it is sometimes possible to be confident about the cause of foundation damage which in turn helps assess the risk presented to the building.

[Click to enlarge any image]

Above: severe damage to a masonry block structural wall. This damage seems to be active and ongoing, though slowly. We suspect that the cracks in this masonry block wall occurred as a defective wall footing began to creep down a steep hill behind the building.

Photographs of types of foundation cracks and other foundation damage: we have a large library of photographs which we're in process of adding these photographs to this website. Pending completion of that work, contact the author if assistance is required.

Questions about active (dynamic) foundation movement

When we find visual or measured evidence of cracking and movement in a masonry foundation wall of any type, there are some diagnostic questions we can ask that help assess the cause of the problem and the urgency of repair actions:

- Constant rate of foundation movement: Does the evidence suggest that cracking and foundation movement are occurring at a constant rate?

- Accelerating rate of foundation movement: Is there evidence that the wall movement is accelerating?

- Decelerating rate of foundation movement: Is there evidence that the wall movement is decelerating?

- Seasonal rate of foundation movement: Is there evidence that the wall movement is seasonal or intermittent? One of our associates has a masonry block garage foundation wall which heaves and moves up and down every spring.

- Site-Work-Related of foundation movement: Is there evidence that the wall movement is related to ongoing site work?

NOTE: without historical data these causes can be difficult to confirm without monitoring. Active movement requires at least monitoring; present or future repair steps likely.

How to Look for evidence of horizontal foundation movement or wall displacement

- Horizontal wall movement: Look for evidence of horizontal wall displacement, lateral displacement such as frost push of a masonry block wall. The bottom block course, held in place by the floor slab, may be in the original location while the first course above or higher courses may have been pushed horizontally inwards.

How to evaluate foundation wall leaning, tipping, or bulging

- Wall tipping or leaning: Look for evidence of wall tipping or leaning - the entire wall has remained flat but leans inwards at the top.

- Wall bulging: Look for evidence of wall bulging, locate the center of the most bulged-in section and note its height above the bottom of the wall and its relative position to the top of grade outside.

How to evaluate the extent and importance of building foundation movement

The crack I'm pointing to in the photo above was observed in a home just a few years old. The crack had been "patched" by smearing mortar over the joint, and where that mortar has fallen away we can see some mortar inside the joint.

When I see that mortar in a patched masonry joint is adhered to one side of the crack and yet a gap still appears, I think movement is active or ongoing. But the total amount of this movement is yet less than 1/8".

Look at

- Where building movement has occurred and where it has not. For example, if cracks in a foundation extend into the supporting footing then movement may be more serious and repair more costly than otherwise

Similarly, movement that is confined to specific building areas or components may excuse from risk wiring, plumbing, chimneys, electrical components that are not present or that do not traverse the movement. - How much building movement has occurred: movement in very small amounts, say 1/6" or 1/8" in most directions won't cause serious damage to most building components but there are exceptions:

Watch out: even small movements that separate fuel piping such as fuel gases, LP gas or natural gas can cause leaks and a fire or dangerous explosion. Similarly, if movement has damaged electrical wiring the building may be unsafe, and finally, disturbance of water supply or drain piping can cause costly damage to a structure.

How to determine the age of foundation cracks & Whether The Cracks are Active or "Static" (Not Moving)

The severely cracked concrete foundation above showed its damage within days of pour of the foundation, before framing had even begun. There was no doubt of the age of the crack; its cause, cure, and prevention of other damage required more on-site analysis.

- Look for clues indicating old vs. new cracks and active vs. static cracks.

For example, evidence of repeated repairs (patched, re-cracked, re-patched) is clear indication of recurrent movement. - Building historical data may tell us about a foundation crack: was there a specific event such as a vehicle parked or driving close to a foundation wall, a flood, earthquake, hurricane or fire? These are key events in building damage history.

- Evidence that a crack occurred at time of construction (in an older house, such as wavy mortar which "bent" in the mortar joints as a wall was loaded) is clear indication of an old condition which may or may not be accompanied by other evidence of later movement.

- Cracks in a concrete or masonry block or brick wall whose edges are sharply defined and "clean" are more likely to be recent.

- Cracks in the same types of structure that, viewed from in doors, say in a basement or crawl area, and that contain dust, dirt, debris deposited by indoor air are more likely to be old.

The "wavy mortar" in the joint of this masonry block wall is like a low-amplitude smooth sine wave, arcing up and down through the middle of a long wall in a home more than a decade old. Yet nowhere is the mortar itself broken. This is old damage that occured during backfill around the foundation at the time of construction, when the mortar was still soft.

Often we'll find a history of water leakage through these open mortar joints and sometimes we'll find wavy mortar, damage during backfill, at a wall that has additional damage from frost or other sources. Keep in mind that multiple conditions may be present at an older building foundation inspection.

Details About What is Inside of a Foundation Wall Wall Crack Suggests Crack History

In this New Jersey office building I saw that the foundation wall had been painted, but there was no paint actually inside of this large "wavy mortar" like crack. My question is: am I looking at an initial backfill damage situation or has there been further wall movement? If I found dust, dirt or other stuff in the crack, even a little paint in the crack I'd think it was old. The building is more than a decade old.

So I've got a contradiction:

Wavy mortar argues for old damage from time of original construction. But the cracks looked so darn clean inside they looked new. But if the wall was painted with a fairly dry roller there may be no paint inside even an old wall crack. But if there had been additional movement in the wall after the "wavy mortar" backfill event wouldn't the wavy mortar itself be broken up? Wouldn't there be other evidence? Closer inspection was needed.

Watch out: don't let yourself get too wedded to your first guess at a diagnosis of any building problem. If you do that you may unconsciously see and accept data that confirms your view and reject data that contradicts it. Try to stay curious as long as you can stand it. Let's get some more data about this crack.

The close look above and just below gave me more information about this foundation wall crack.

The two photos above show that there was both dirt/dust at a thick level in portions of this crack, and in some areas along the wall green paint had flowed into the crack as well. How long ago had this wall been painted? Is the paint much newer than the wall. The paint sure looked new.

This last "cracks in the green block wall from New Jersey" photo clinched the argument for me. I found not only a good dose of green paint inside the crack (so the wall was painted after the crack occurred), I also found blobs of dirt and dust in the crack that themselves had been painted.

I was satisfied that this was an "wavy mortar" old crack situation that had occurred at the time of initial backfill when the building was constructed. It makes sense to keep alert for other clues that support or make you question such assumptions.

How to measure the amount of lean or bulge in a foundation wall

When I inspected the home above (in 1997) it was more than 40 years old. My client is pointing to a rectangular metal plate serving as a giant "washer" beneath a nut on the end of an anchor rod that was driven through the wall into the soil below.

We know some of the history of the home from just this observation: someone was attempting to repair a bulging or leaning foundation.

The natural questions is: Is this wall OK? Is there a threat to the structure? Are more repairs needed? One step is to take a look at how much movement has occurred in the wall - measure its bulge. Another is to look for signs of repeated or ongoing movement.

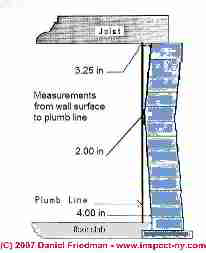

Measuring foundation wall tip, lean, or bulge: is simple: drop a plumb line near the most-bulged area (usually the center) of the wall, perhaps fastening it to a nail in a floor joist overhead, about 4" in from the wall. Measure from the string in to the wall at various heights up the wall.

The concrete block foundation wall above is visibly bulged inwards and water-stained. Let's look at a couple of details.

Above I see mud and dirt coming through the wall; there's little question that the other side of this wall has been exposed to soaking wet soil, wet soil pressure and maybe frost pressure too. Certainly there will be frost pressure if the home is in a freezing climate. (It is, or it used to be before global warming.)

Above I'm demonstrating that there is also horizontal dislocation in the wall: my pen laid against the upper block is about 1/4" away from the surface of the lower block in an imprecise but interesting observation. This is a wall that is ugly, bulged, moving, and needs to be re-built. In my OPINION it's too messed up with too many broken joints to just stiffen with pilasters or horizontal earth anchors.

At DIAGONAL CRACKING, SEVERE you can see some walls about to collapse. Below you can see what could be coming. As Chip says "You don't wanna go there".

You'll be able

to easily pinpoint the height of the most bulge or lean. This is not engineering. It's simple a simple mason's method to measure a wall or chimney during

construction to keep it plumb.

[You may need to hire the services of a licensed professional engineer, one who is

experienced with foundation troubleshooting and repair, especially if there is need to design a special building

repair method or if there is apparent risk of possible building instability or collapse.]

The Position of Most-Bulged Point in Wall Is Diagnostic

- Wall most-bulged in near the outdoor ground surface (commonly occurs in the upper 1/2 of the wall), perhaps at a depth equal to the frost line in climates where freezing occurs or in the top 1/3 of the wall if we suspect water or frost loading on the wall, or possibly vehicle traffic driving too close to the wall.

- Wall most-bulged in at its center height - the center of the overall height of the wall (common) - we suspect vehicle traffic or possibly water/earth loading

- Wall most-bulged in near its bottom (unusual) - we suspect earth loading or wet earth loading.

Details: a plumb line, that is a string suspended by a weight, gives a perfectly vertical line from which to measure back to the wall surface. We don't care about the absolute value of the various measurements, we care about the difference between these measurements.

Usually the very bottom of a building wall will not have moved inwards, particularly if a concrete floor has been poured against the foundation.

The entire building floor slab is acting as an "anchor" to hold the bottom of the foundation wall in place. So we take the distance between the foundation wall and the string at the bottom of the wall as our "home base" or point of assumed "zero movement".

We compare this measured value with the other measurements between the wall and the string. If the foundation wall or any part of it higher than the floor has moved, tipped, or bulged inwards, those measurements from wall-to-string will be less than the distance, wall-to-string measured just above the floor level. That's because the wall has moved inwards, towards the string.

An example of measuring the amount of foundation wall bulge inwards

- We "eyeball" the "bulged" foundation wall and guess at the point at which it is bulged inwards the most - perhaps close to the center of the length of the wall (right-to-left dimension)

- We hang our string or plumb line from the nearest floor joist, keeping the string a few inches away from the foundation wall

- We measure 4.00 inches between the foundation wall surface to our vertical plumb-line string at 1" above the concrete floor - this is our "zero point" or "home base" measurement

- We measure 2.00 inches from the same foundation wall surface to our vertical string at a height of 5' from the floor

- We measure 3.25 inches from the same foundation wall surface to our vertical string at the very top of the wall just under the sill plate.

- We check that we've measured at the area of greatest inward bulge in the wall by moving our plumb line to our left, then to our right on either side of the ceiling joist we used to hang the string for our first measurement. If the distances we measure, wall to string, are greater than the distances we measured at our first trial, then that one is the point of greatest inwards foundation wall bulge.

- Finally we do the math: subtract our "higher on wall" and "closer to string" measurements from our "at the floor" and "farthest from string" measurement. We see these results:

- Foundation Wall Bulge-in at floor = 0 inches

- Foundation Wall Bulge-in at 5'up from floor = 4" - 2" = 2" of inwards bulge

- Foundation Wall Bulge-in at the top of the wall = 4" - 3.25" = .75" of inwards lean

How to distinguish between a "bulged" foundation wall and a "leaning" foundation wall, and why we care

Characteristics of a leaning foundation wall

If all of our measurements of inwards movements in the foundation wall increase in distance (wall to string), from floor up towards the top of the wall, the wall is leaning inwards. In this case we'd expect to not see horizontal cracks (if the wall is masonry block, for example).

Characteristics of a bulging foundation wall

If our measurements anywhere between the floor and the top of the wall is greater than the distance measured (wall to string) at the floor bottom and at the wall top then the wall is "bulged" inwards at that point. If the wall is masonry block in construction we'd expect to see horizontal cracks in one or mortar joints in the bulged area, with the widest horizontal crack at or close to the point of greatest inward bulge.

Even a concrete wall which is bulged is going to be cracked horizontally, though perhaps not in such a straight line. But a bulged reinforced concrete wall would be very rare unless perhaps the concrete wall bulged, or its forms bulged, during the time that the concrete was being poured and was still wet.

Other cases of leaning or moved foundation walls may produce different measurements

Horizontal foundation wall movement, creep, non-leaning lateral shift

On less frequent occasions we've found that an entire masonry block wall (or portions of it) were pushed horizontally inwards by some outside force, without causing the wall to lean or bulge. In a pure example of such a case, all of the differential movement measured (wall to string) between the wall bottom point (held in place by the floor slab) and the inwards-pushed wall section, will be a horizontal movement of that portion of the wall, and if it's masonry block, you'll see that the inwards-moved blocks are "hanging over" or projecting past the surface of the masonry blocks that did not move.

Combinations of foundation wall movement

You may encounter a foundation wall which has moved inwards in a combination of forms, both bulging at its most-pushed-in point (with horizontal cracks in the foundation wall) and the wall may have also been pushed inwards sliding some of the masonry blocks inwards past others which have remained in place.

In this case you'll see both that some masonry wall blocks will overhang or protrude past others in the wall (usually upper inwards pushed blocks hang over lower more stable blocks closer to the floor), and there may be bulging and cracking at another elevation of the wall.

Step cracks in building foundations may also be present in bulged, leaning, or horizontally pushed foundation walls if they were constructed of brick or masonry block, or possibly (though less common) of stone.

In fact since the building foundation corners are stronger than the center portions of the foundation wall (the opposing wall at right angle resists movement of the wall being pushed), wall bulges, leans, and cracks tend to occur towards the center of the wall, resulting in step-cracking closer to the ends of the same wall.

Other step cracks will of course also occur in building masonry block foundation walls that are not leaning or bulging particularly, where frost or settlement have been causing an "up and down" movement in the foundation or footing.

Other vertical cracks can occur in a masonry block or concrete or brick or stone foundation wall without leaning or bulging if the wall is moving due to footing settlement or frost.

...

Continue reading at FOUNDATION MOVEMENT COMBINATIONS or select a topic from the closely-related articles below, or see the complete ARTICLE INDEX.

Or see these

Foundation Movement Articles

- FOUNDATION DAMAGE SEVERITY

- FOUNDATION FAILURES by MOVEMENT TYPE

- BRICK WALL THERMAL EXPANSION

- BULGED vs. LEANING FOUNDATIONS

- CONTROL JOINT CRACKS in CONCRETE

- DIAGONAL CRACKS in CONCRETE FOUNDATIONS, WALLS

- DIAGONAL CRACKS in BLOCK FOUNDATIONS, WALLS

- EARTHQUAKE DAMAGED FOUNDATIONS

- FOUNDATION MOVEMENT ACTIVE vs. STATIC

- FOUNDATION MOVEMENT COMBINATIONS

- FOUNDATION SETTLEMENT

- FROST HEAVE / EXPANSIVE SOIL

- HORIZONTAL FOUNDATION CRACKS

- HORIZONTAL MOVEMENT

- SETTLEMENT CRACKS in SLABS

- SETTLEMENT vs. FROST HEAVE CRACKS

- SETTLEMENT vs. SHRINKAGE CRACKS

- SHRINKAGE CRACKS in SLABS

- SHRINKAGE GAPS at WALLS

- THERMAL EXPANSION CRACKS

- VERTICAL MOVEMENT IN FOUNDATIONS

- FOUNDATION INSPECTION STANDARDS

Suggested citation for this web page

FOUNDATION MOVEMENT ACTIVE vs. STATIC at InspectApedia.com - online encyclopedia of building & environmental inspection, testing, diagnosis, repair, & problem prevention advice.

Or see this

INDEX to RELATED ARTICLES: ARTICLE INDEX to BUILDING STRUCTURES

Or use the SEARCH BOX found below to Ask a Question or Search InspectApedia

Ask a Question or Search InspectApedia

Try the search box just below, or if you prefer, post a question or comment in the Comments box below and we will respond promptly.

Search the InspectApedia website

Note: appearance of your Comment below may be delayed: if your comment contains an image, photograph, web link, or text that looks to the software as if it might be a web link, your posting will appear after it has been approved by a moderator. Apologies for the delay.

Only one image can be added per comment but you can post as many comments, and therefore images, as you like.

You will not receive a notification when a response to your question has been posted.

Please bookmark this page to make it easy for you to check back for our response.

IF above you see "Comment Form is loading comments..." then COMMENT BOX - countable.ca / bawkbox.com IS NOT WORKING.

In any case you are welcome to send an email directly to us at InspectApedia.com at editor@inspectApedia.com

We'll reply to you directly. Please help us help you by noting, in your email, the URL of the InspectApedia page where you wanted to comment.

Citations & References

In addition to any citations in the article above, a full list is available on request.

- "Concrete Slab Finishes and the Use of the F-number System", Matthew Stuart, P.E., S.E., F.ASCE, online course at www.pdhonline.org/courses/s130/s130.htm

- Sal Alfano - Editor, Journal of Light Construction*

- Thanks to Alan Carson, Carson Dunlop, Associates, Toronto, for technical critique and some of the foundation inspection photographs cited in these articles

- Terry Carson - ASHI

- Mark Cramer - ASHI

- JD Grewell, ASHI

- Duncan Hannay - ASHI, P.E. *

- Bob Klewitz, M.S.C.E., P.E. - ASHI

- Ken Kruger, P.E., AIA - ASHI

- Aaron Kuertz aaronk@appliedtechnologies.com, with Applied Technologies regarding polyurethane foam sealant as other foundation crack repair product - 05/30/2007

- Bob Peterson, Magnum Piering - 800-771-7437 - FL*

- Arlene Puentes, ASHI, October Home Inspections - (845) 216-7833 - Kingston NY

- Greg Robi, Magnum Piering - 800-822-7437 - National*

- Dave Rathbun, P.E. - Geotech Engineering - 904-622-2424 FL*

- Ed Seaquist, P.E., SIE Assoc. - 301-269-1450 - National

- Dave Wickersheimer, P.E. R.A. - IL, professor, school of structures division, UIUC - University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign School of Architecture. Professor Wickersheimer specializes in structural failure investigation and repair for wood and masonry construction. * Mr. Wickersheimer's engineering consulting service can be contacted at HDC Wickersheimer Engineering Services. (3/2010)

- *These reviewers have not returned comment 6/95

ADDITIONAL READING about Foundation Failure Diagnosis & Repair

- Diagnosing & Repairing House Structure Problems, Edgar O. Seaquist, McGraw Hill, 1980 ISBN 0-07-056013-7 (obsolete, incomplete, missing most diagnosis steps, but very good reading; out of print but used copies are available at Amazon.com, and reprints are available from some inspection tool suppliers). Ed Seaquist was among the first speakers invited to a series of educational conferences organized by D Friedman for ASHI, the American Society of Home Inspectors, where the topic of inspecting the in-service condition of building structures was first addressed.

- Design of Wood Structures - ASD, Donald E. Breyer, Kenneth Fridley, Kelly Cobeen, David Pollock, McGraw Hill, 2003, ISBN-10: 0071379320, ISBN-13: 978-0071379328

This book is an update of a long-established text dating from at least 1988 (DJF); Quoting:

This book is gives a good grasp of seismic design for wood structures. Many of the examples especially near the end are good practice for the California PE Special Seismic Exam design questions. It gives a good grasp of how seismic forces move through a building and how to calculate those forces at various locations. THE CLASSIC TEXT ON WOOD DESIGN UPDATED TO INCLUDE THE LATEST CODES AND DATA. Reflects the most recent provisions of the 2003 International Building Code and 2001 National Design Specification for Wood Construction. Continuing the sterling standard set by earlier editions, this indispensable reference clearly explains the best wood design techniques for the safe handling of gravity and lateral loads. Carefully revised and updated to include the new 2003 International Building Code, ASCE 7-02 Minimum Design Loads for Buildings and Other Structures, the 2001 National Design Specification for Wood Construction, and the most recent Allowable Stress Design. - Building Failures, Diagnosis & Avoidance, 2d Ed., W.H. Ransom, E.& F. Spon, New York, 1987 ISBN 0-419-14270-3

- Domestic Building Surveys, Andrew R. Williams, Kindle book, Amazon.com

- Defects and Deterioration in Buildings: A Practical Guide to the Science and Technology of Material Failure, Barry Richardson, Spon Press; 2d Ed (2001), ISBN-10: 041925210X, ISBN-13: 978-0419252108. Quoting:

A professional reference designed to assist surveyors, engineers, architects and contractors in diagnosing existing problems and avoiding them in new buildings. Fully revised and updated, this edition, in new clearer format, covers developments in building defects, and problems such as sick building syndrome. Well liked for its mixture of theory and practice the new edition will complement Hinks and Cook's student textbook on defects at the practitioner level. - Guide to Domestic Building Surveys, Jack Bower, Butterworth Architecture, London, 1988, ISBN 0-408-50000 X

- "Avoiding Foundation Failures," Robert Marshall, Journal of Light Construction, July, 1996 (Highly recommend this article-DF)

- "A Foundation for Unstable Soils," Harris Hyman, P.E., Journal of Light Construction, May 1995

- "Backfilling Basics," Buck Bartley, Journal of Light Construction, October 1994

- "Inspecting Block Foundations," Donald V. Cohen, P.E., ASHI Reporter, December 1998. This article in turn cites the Fine Homebuilding article noted below.

- "When Block Foundations go Bad," Fine Homebuilding, June/July 1998

- Avongard FOUNDATION CRACK PROGRESS CHART [PDF] - structural crack monitoring

- Building Pathology: Principles and Practice, David Watt, Wiley-Blackwell; 2 edition (March 7, 2008) ISBN-10: 1405161035 ISBN-13: 978-1405161039

- Diagnosing & Repairing House Structure Problems, Edgar O. Seaquist, McGraw Hill, 1980 ISBN 0-07-056013-7 (obsolete, incomplete, missing most diagnosis steps, but very good reading; out of print but used copies are available at Amazon.com, and reprints are available from some inspection tool suppliers). Ed Seaquist was among the first speakers invited to a series of educational conferences organized by D Friedman for ASHI, the American Society of Home Inspectors, where the topic of inspecting the in-service condition of building structures was first addressed.

- Building Failures, Diagnosis & Avoidance, 2d Ed., W.H. Ransom, E.& F. Spon, New York, 1987 ISBN 0-419-14270-3

- Domestic Building Surveys, Andrew R. Williams, Kindle book, Amazon.com

- Defects and Deterioration in Buildings: A Practical Guide to the Science and Technology of Material Failure, Barry Richardson, Spon Press; 2d Ed (2001), ISBN-10: 041925210X, ISBN-13: 978-0419252108. Quoting:

A professional reference designed to assist surveyors, engineers, architects and contractors in diagnosing existing problems and avoiding them in new buildings. Fully revised and updated, this edition, in new clearer format, covers developments in building defects, and problems such as sick building syndrome. Well liked for its mixture of theory and practice the new edition will complement Hinks and Cook's student textbook on defects at the practitioner level. - Guide to Domestic Building Surveys, Jack Bower, Butterworth Architecture, London, 1988, ISBN 0-408-50000 X

- "Avoiding Foundation Failures," Robert Marshall, Journal of Light Construction, July, 1996 (Highly recommend this article-DF)

- "A Foundation for Unstable Soils," Harris Hyman, P.E., Journal of Light Construction, May 1995

- "Backfilling Basics," Buck Bartley, Journal of Light Construction, October 1994

- Quality Standards for the Professional Remodeling Industry, National Association of Home Builders Remodelers Council, NAHB Research Foundation, 1987.

- Quality Standards for the Professional Remodeler, N.U. Ahmed, # Home Builder Pr (February 1991), ISBN-10: 0867183594, ISBN-13: 978-0867183597

- Slab on Grade Foundation Moisture and Air Leakage, U.S. Department of Energy

- In addition to citations & references found in this article, see the research citations given at the end of the related articles found at our suggested

CONTINUE READING or RECOMMENDED ARTICLES.

- Carson, Dunlop & Associates Ltd., 120 Carlton Street Suite 407, Toronto ON M5A 4K2. Tel: (416) 964-9415 1-800-268-7070 Email: info@carsondunlop.com. Alan Carson is a past president of ASHI, the American Society of Home Inspectors.

Thanks to Alan Carson and Bob Dunlop, for permission for InspectAPedia to use text excerpts from The HOME REFERENCE BOOK - the Encyclopedia of Homes and to use illustrations from The ILLUSTRATED HOME .

Carson Dunlop Associates provides extensive home inspection education and report writing material. In gratitude we provide links to tsome Carson Dunlop Associates products and services.