Climbing Up or Down Stairs

Climbing Up or Down Stairs

Photos of hand & foot placement when using a stairway

- POST a QUESTION or COMMENT on details about recognizing common stair trip and fall hazards.

How people walk up and down stairs:

Stair slip trip & fall hazards and their prevention may benefit from a look at just how people step when ascending and descending stairs and what they do with handrailings or where they place their hands when there is no handrail.

Page top photo: an elderly walker wearing sandals ascends wide-tread low-rise uneven-surfaced stone steps in Tlaxcala, Mexico.

Notice the very low-rise light-red stone step-up just ahead in his walking path: another trip hazard. Some older people and others who suffering from physical or neurological injury may shuffle or fail to adequately lift a foot when walking, increasing their risk of a trip and fall over even very low irregularities in the walking surface.

Notice also that the walker's heel extends out over the nose of the stone step under his right foot. If the step nose is damaged, sloped, or slippery a fall is likely.

InspectAPedia tolerates no conflicts of interest. We have no relationship with advertisers, products, or services discussed at this website.

- Daniel Friedman, Publisher/Editor/Author - See WHO ARE WE?

How People Use Stairs & Handrails

There is an enormous body of research on stair falls, injuries, and their cause and prevention. Here, with no pretense at repeating that scholarly work, we focus on twenty-years of photographs of just how people place their hands and feet when ascending or descending stairs.

There is an enormous body of research on stair falls, injuries, and their cause and prevention. Here, with no pretense at repeating that scholarly work, we focus on twenty-years of photographs of just how people place their hands and feet when ascending or descending stairs.

We have been particularly interested in observing people making use of difficult or obviously-dangerous steps.

These photographs of stair and step & walk defects provide a photo-catalog how people climb or descend steps or stairs under various circumstances including tall rise steps, narrow tread depth steps, damaged or irregular-surfaced steps, curved steps, carpeted steps, dimly-lit steps, icy or slippery steps, and stairways where there is either a non-graspable handrail or no handrail at all.

Most stair falls occur when walking down stairs, and most of those involve a combination of slip, trip, or fall hazards in the stair design or the condition of its walking surface.

Photo: names of the basic dimensions of steps and risers on a rough stairway at a pyramid at Canada de la Virgin.

[Click to enlarge any image]

Falls down stairs are more-likely, and more-likely to result in more-serious injury when handrailings are absent or defective as well - a condition that sacrifices the opportunity to prevent, arrest, or reduce the extent of a fall.

Foot Positions When Walking Down Stairs

Where do people walk when descending a stairway: along a wall, along the handrail, or wherever the stairs feel safest.

Above: a typical stair descent viewed through an unsafe stair guard (balusters too far apart). The front half or often the ball of a stair user's feet often hinge over the tread nose on the steps.

Above: where there is no handrail nor stair guard on the open side of these stairs in San Luis Potosi, the walkers naturally descend close to the wall along the stairway closed-side.

Walking Down Slippery or Icy Stairs

Walkers are naturally cautious when the slip hazards are visually obvious, such as this stairway. Descending these ice-covered steps and landings in Northern Minnesota is a familiar task to local residents but treacherous nevertheless.

With my camera back in my pocket I held onto the handrailing on the left side of the steps with both hands and attempted to go down the steps and across the icy landing.

Even holding on with both hands and prepared for the slippery surface, I slipped and fell in the middle of the landing.

The park service had posted a sign recommending that crampons were recommended for this path.

Walking Down Carpeted Stairs

Sometimes a walker is inclined to walk or even forced to walk too far from the handrailing for a good grasp.

Above: in Carnegie Hall in New York City steps in the upper balcony are tall, carpeted, and at times only dimly-lit. The hall has provided a good color code to help mark the edge of each stair tread.

The patron, elderly and walking with a cane, grasps the handrail along her left but has to extend her arm fully to permit her to step along the right side of the steps as she tried to avoid walking on the curved portion of the stairs closer to the handrailing.

In this position should she slip, with her left arm fully extended it will be more difficult to retain her grasp of the handrail.

Foot Positions When Walking Up Stairs

Below: Walkers up these tall and narrow-tread steps at Canada de la Virgin in Guanajuato demonstrate a dramatic situation: the mom, using both hands to carry their baby, is assisted by the dad. Should she slip she has no free hand (and no handrailing) to arrest the fall.

Above: tourists ascending a steep stairway, the mom carries the baby, having no hands free.

Below: climbing the Pyramid of the Sun in Mexico City a cable or rope handrail helps the ascent up this very long stairway.

Stepping up where only a sign points the way this older tourist was inclined to skip a low-rise step.

Below: ascending steps that are regular and in decent condition, we notice that often half of the climber's foot extends out over the edge of each tread as she steps up.

Walking Up & Down Open Riser Stairs

On open riser stairs this user demonstrates that the toe of the foot can inadvertently extend under the next stair tread above, forming a possible trip hazard.

When descending the same type of open riser steps the toe trap problem doesn't occur.

Walking Up Alternating Tread Stairs

Common on shipboard where horizontal space is limited, alternating tread stairs have a following among designers who need to jam a stair into a space where there is no space for a longer stairway horizontal run. I found these steps awkward to climb with still a too-tall step rise.

Experts consider these steps a safe design that permits climbing steps with a slope as much as 70° (usually 65° or less ) - steeper than ordinary stairs. (Friedlander 2009). Alternating tread steps to access mechanicals or other high areas are permitted in industry provided the stair angle is 70°or less, with handrails on both sides

. The stair must support a uniform load of 100 psi/square foot with a design safety factor of 1.7, and each tread must be able to carry a concentrated load of 300 pounds at the center of the tread.

Walking Up & Down Narrow-Tread Stairs

Above: the heel extends well off of the stair tread if the user tries to walk normally up a shallow-depth or narrow-tread step.

Above: as a result most people confronting a very narrow stair tread like the one above (Becan, Campeche, Yucatan, Mexico) will place their foot sideways along the width rather than the depth of the step or tread. At least that's what I was doing.

Above: a couple descending slightly-deeper stone treads at Canada de la Virgin in Guanajuato illustrate that placed lengthwise along the width of the step stepping down is still treacherous.

Notice the red T-shirted walker's left foot is along the sloped, irregular nose of the step as he helps the yellow-T-shirted companion descend sideways.

Above: a younger and less-cautious walker has both feet at more-dangerous angles along the edge of stair treads as he steps down these same steps.

Below in Campeche a tourist resorts to sitting on the steps to use both hands and feet to descend the steep and worn stone steps of this pyramid.

Stepping on the Stair Nose

Above: because walking-up people often place the ball of their foot right on the stair tread nose, if the nose is cracked or damaged, the risk of a fall is increased.

Below: walking down a concrete and stone stairway in Tlaxcala, where concrete has broken away from the step and the walker steps half-into the broken nose area, the foot tends to slip sideways wrenching the ankle and inviting a fall.

Walking Up or Down Stairs With & Without Color Contrast

Above: we added this stair edge phosphorescent tape to reduce falling hazards at the brick stairs whose surface matched the floor above in this Poughkeepsie NY home.

Below: the stair builder provided white and black tiles to give a good color clue that there is a step to be negotiated.

Crawling Up or Down Stairs

Walking on Low-Rise Long-Run Stairs

Above: toe catching wet landscape ties at an outdoor stair.

Below: it is nearly impossible to see variations in level among the three walking surfaces in this restaurant.

Using Stairway Handrailings

Walking Up Stairs With Handrails Present

Along the Genoa Italy coast an older tourist negotiates angled steps grasping the handrailing and using a cane.

Walking Down Stairs with Handrailing Present

Walking Down Angled, Circular or Curved Stairs With Handrailings

Angled and curved steps are common trip hazards.

During a building inspection the author stood looking at half-round steps like the ones above but those graced the entry to a home. The client, Mr. Buyer, admired the creative step design. I commented that I thought the round steps meant that a user was more likely to fall. As I completed the sentence Mrs. Buyer stepped out of the entry door and, looking at her husband, stepped out and fell down the stairs.

Walking Down Stairs with Non-Graspable Handrail

No one can grasp a wide handrailing like the one in our photo above, nor use it to arrest a fall. However it is nice to lean-on.

My daughter Mara fell down these angled stairs (above) where the very fat upper guardrail surface was the only "handrail" provided (red arrow).

When I took this photo the shopping center had decided to weld-on a lower, more-graspable handrailing (green arrow).

Above: non-graspable handrailing is used by this stair user to help balance while walking down the stairs.

Walking Down Stairs with Low Handrail

Below: this guard along the stairway is not graspable and is too low even to use to help keep one's balance.

Below I'm illustrating a too-low handrail down too-steep basement stairs - also there's no guard railing.

Walking Down Stairs with a Graspable Handrail

At the Castle Point Veterans Administration center this stair guard and handrailing work together to help a population that includes people who have difficulty with stairs.

Above: my sister Linda Ann demonstrated that using this stair newel to try to maintain one's balance is going to be difficult.

See details at NEWEL POST CONSTRUCTION

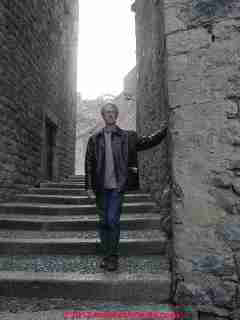

Walking Up Stairs Without Handrailings

In the photo above, Nizar is demonstrating how he hangs onto the door gate from a narrow top step (missing a an entry landing platform) to open the front door to this home in Rabat, Morocco.

Above: a youngster climbing the pyramid at Canada de la Virgin leans against stone wall remains to help his balance.

Where there are no handrails and other step hazards (irregular step rise, narrow step depth, uneven step surfaces all shown here), when ascending the climber will either touch a wall (if present) or may touch steps higher in the flight to maintain balance - above.

Below: Stairway uses also find it easier to maintain balance while looking down at the stair treads when ascending than when descending the same stairs.

Below: a youngster uses hands, knees, and feet to climb tall treads that are still taller for a child than an adult. Notice that those smaller feet fit better on the shallow depth stair treads.

Walking Down Stairs with No Handrailing

Above: where there are no handrails an elderly stairway user (me) may lean along the wall to keep balance but the absence of a handrailing means there's little chance to arrest a fall.

Above: stair users all leaning against and balancing using a wide stone wall along a pyramid's stairway.

Above: stair users in the antique Post Office in Cd. Mexico descend the final three steps and four risers of a double-curved stairway where there are no handrails. The stairs are, however, exceptionally beautiful.

Below: a walker descends open riser stairs with treads that are too narrow: the tread depth is too small. The tread inner edge is several inches out from below the front edge or nose of the tread above. It's easy to accidentally step into this space.

Walking Down Stairs with a Non-Continuous Handrail at Landings

A window in a stair landing such as the one shown here requires a guard to prevent someone from falling through and out of the window.

In addition the absence of a continuous handrailing around the landing increases the fall risk, especially for elderly occupants or others with limited mobility. An elederly neighbor fell down this stairway and became permanently disabled. [DF]

Above: at PLATFORMS & LANDINGS, ENTRY & STAIR a reader describes a stair fall and injury at these stairs that include four wrap-around bottom treads with no handrailing on the side that most people will use to descend and step towards the building entry door.

Walking & ripping over Micro-Steps

Stubbed toes. Trips, falls.

Research on Common Stair Falls & Hand or Foot Placement & Handrail Use

- CONSTRUCTION WORK STAIR CODE [PDF] retrieved 2018/08/22 original source: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.381.7999&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- Cohen, Joseph, and H. Harvey Cohen. "Hold on! An observational study of staircase handrail use." In Proceedings of the human factors and ergonomics society annual meeting, vol. 45, no. 20, pp. 1502-1506. Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications, 2001.

Abstract:

Handrails are the primary safety devices installed on staircases, yet it has not been empirically determined to what extent they are actually used. This study selected two staircases, one long and wide and another short and narrow, serving a newly remodeled shopping mall. Variables observed were: handrail use, ascent/descent, number of hands free, within arm's reach, gait, gender, and age.

Less than a third of all staircase users utilized a handrail, with the likelihood of use increasing with age. Overall, 59% were observed to place themselves within arm's reach of a handrail. Staircase users were more likely to be within arm's reach during descent. Women were more likely to have just one hand free, while men more frequently had both hands free.

Handrail use was observed to be 10% greater during descent than ascent. The study shows that even with handrails having high usability characteristics, actual handrail use is minimal. T

his finding has implications for behavioral compliance in situations where a safety device is provided, but its need is not perceived to be immediate. - de Vries, David A. "Emerging issues in high-rise building egress." [PDF] Fire Protection Engineering 31 (2006): 16. - retrieved 2018/08/22, original source: http://www.elje4firesafety.com/eng/images/ file_artikel/Emerging Issues in High-Rise Building Egress.pdf

- Ellis, Nigel J, FALL PREVENTION [PDF] Professional Sfaety, November 2012, Website: www.asse.org, retrieved 2018/08/22 original source: https://www.fallsafety.com/pdfs/three_point.pdf

- Muhaidat, Jennifer, Andrew Kerr, Danny Rafferty, Dawn A. Skelton, and Jonathan J. Evans. "Measuring foot placement and clearance during stair descent." [PDF] Gait & posture 33, no. 3 (2011): 504-506.

Abstract:

Falls during stair descent are a serious problem and can lead to accidental death. Inappropriate foot placement on, and clearance over, steps have been identified as causes for falls on stairs. This study investigated a new method for measuring placement and clearance during stair descent in 10 healthy young subjects.

The effect of foot length was accounted for during the measurement of foot placement by calculating the percentage length of the foot overhanging the step. Foot clearance was measured as the resultant of the minimum vertical and horizontal distances from the heel of the foot to the edge of the step.

Clearance was divided into landing and passing clearance depending on the planned placement of the foot in relation to the step edge being cleared. Each subject performed seven trials of stairs descent. Mean (SD) and CV (SD) were 16% (6), 0.28 (0.15) for placement; 45.88 (10.05), 0.21 (0.07) for landing clearance; 107.25 (5.59), 0.25 (0.08) for passing clearance.

There was no statistically significant effect of trial on placement and clearance (p > 0.05). There was a significant effect of step number on landing and passing clearance (p = 0.01, p < 0.001 respectively).

Landing and passing clearances were greater for the third step compared to the second step. Passing clearance was also significantly greater than landing clearance (p < 0.001). The repeatable methods and findings from this study might be useful in providing a technical background and normal values for the design of future gait studies on stairs. - Riazi, Abbas, Mei Ying Boon, Catherine Bridge, and Stephen J. Dain. "Home modification guidelines as recommended by visually impaired people." Journal of Assistive Technologies 6, no. 4 (2012): 270-284.

- Roys, Mike. "Steps and stairs." Understanding and Preventing Falls: An Ergonomics Approach (2004): 42.

- Roys, Michael S. "Serious stair injuries can be prevented by improved stair design." Applied ergonomics 32, no. 2 (2001): 135-139.

- Sheehan, Riley C., and Jinger S. Gottschall. "At similar angles, slope walking has a greater fall risk than stair walking." Applied ergonomics 43, no. 3 (2012): 473-478.

Abstract:

According to the CDC, falls are the leading cause of injury for all age groups with over half of the falls occurring during slope and stair walking.

Consequently, the purpose of this study was to compare and contrast the different factors related to fall risk as they apply to these walking tasks. More specifically, we hypothesized that compared to level walking, slope and stair walking would have greater speed standard deviation, greater ankle dorsiflexion, and earlier peak activity of the tibialis anterior.

Twelve healthy, young male participants completed level, slope, and stair trials on a 25-m walkway. Overall, during slope and stair walking, medial–lateral stability was less, anterior–posterior stability was less, and toe clearance was greater in comparison to level walking. In addition, there were fewer differences between level and stair walking than there were between level and slope walking, suggesting that at similar angles, slope walking has a greater fall risk than stair walking - Simoneau, Guy G., Peter R. Cavanagh, Jan S. Ulbrecht, Herschel W. Leibowitz, and Richard A. Tyrrell. "The influence of visual factors on fall-related kinematic variables during stair descent by older women." Journal of gerontology 46, no. 6 (1991): M188-M195.

Abstract:

Despite the documented health hazards associated with stair descent, the mechanisms of falling on stairs remain relatively unexamined. The objectives of this study were to define kinematic variables that could be used to describe foot-stair spatial relationships during the mid-stair phase of stair descent, and to investigate the effects of various visual and environmental conditions on those variables in a group of 36 healthy women between the ages of 55 and 70.

Foot clearance and foot placement were measured through high-speed film analysis.

Clearance between the foot and the stair during swing phase was small under all visual conditions. Degraded visual acuity had a significant effect on cadence, foot placement, and foot clearance, but visual surround conditions did not.

The kinematic variables used in this experiment may be helpful in future studies to assess the results of interventions aimed at reducing the frequency of falls on stairs. - Schiller JS, Kramarow EA, Dey AN "Fall Injury episodes among noninstitutionalized older adults: United States 2001-2003", Division of Health Interview Statistics and Office of Analysis and Epidemiology, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville MD 20782, USA, Adv. Data 2007 Sep 21;(392);1-16. [Book] Abstract comments:

Objective—This report presents national estimates of fall injury episodes for noninstitutionalized U.S. adults aged 65 years and over, by selected characteristics. Circumstances surrounding the fall injury and activity limitations and utilization of health care resulting from the fall injury are also presented.

Methods—Combined data from the 2001–2003 National Health Interview Surveys (NHIS), conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), were analyzed to produce estimates for the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population. Data on nonfatal medically attended fall injuries occurring within the 3 months preceding the interview were obtained from an adult family member.

Results—The annualized rate of fall injury episodes for noninstitutionalized adults aged 65 years and over in 2001–2003 was 51 episodes per 1,000 population. Rates of fall injuries increased with age, and were higher for women compared with men. Non-Hispanic white older adults had higher rates of fall injuries compared with non-Hispanic black older adults.

Older adults with certain chronic conditions and activity limitations had higher rates of fall injuries compared with older adults without these conditions.

The most common cause of fall injuries among older adults was slipping, tripping, or stumbling, and most fall injuries occurred inside or around the outside of the home. Nearly 60 percent of older adults who experienced a fall injury visited an emergency room for treatment or advice. Nearly one-third of older adults experiencing a fall injury needed help with activities of daily living as a result, and over one-half of these persons expected to need this help for at least 6 months.

A similar percentage experienced limitation in instrumental activities of daily living as a result of fall injuries.

Conclusion—Fall injuries remain very prevalent among older adults and result in high health care utilization and activity limitations. Rates of fall injuries vary by demographic and health characteristics of older noninstitutionalized adults.

Keywords: National Health Interview Survey c injury episodes c injury prevention - Vallabhajosula, Srikant, Chi Wei Tan, Mukul Mukherjee, Austin J. Davidson, and Nicholas Stergiou. "Biomechanical analyses of stair-climbing while dual-tasking." Journal of biomechanics 48, no. 6 (2015): 921-929.

Abstract:

Stair-climbing while doing a concurrent task like talking or holding an object is a common activity of daily living which poses high risk for falls. While biomechanical analyses of overground walking during dual-tasking have been studied extensively, little is known on the biomechanics of stair-climbing while dual-tasking.

We sought to determine the impact of performing a concurrent cognitive or motor task during stair-climbing.

We hypothesized that a concurrent cognitive task will have a greater impact on stair climbing performance compared to a concurrent motor task and that this impact will be greater on a higher-level step. T

en healthy young adults performed 10 trials of stair-climbing each under four conditions: stair ascending only, stair ascending and performing subtraction of serial sevens from a three-digit number, stair ascending and carrying an empty opaque box and stair ascending, performing subtraction of serial sevens from a random three-digit number and carrying an empty opaque box.

Kinematics (lower extremity joint angles and minimum toe clearance) and kinetics (ground reaction forces and joint moments and powers) data were collected. We found that a concurrent cognitive task impacted kinetics but not kinematics of stair-climbing.

The effect of dual-tasking during stair ascent also seemed to vary based on the different phases of stair ascent stance and seem to have greater impact as one climbs higher.

Overall, the results of the current study suggest that the association between the executive functioning and motor task (like gait) becomes stronger as the level of complexity of the motor task increases. - [9] Slip, Trip, and Fall Prevention: A Practical Handbook, Second Edition Steven Di Pilla, CRC Press; 2 edition (July 28, 2009), ISBN-10: 1420082345

ISBN-13: 978-1420082340, Abstract:

More than one million people suffer from a slip, trip, or fall each year and 17,700 died as a result of falls in 2005. They are the number one preventable cause of loss in the workplace and the leading cause of injury in public places. Completely revised, Slip, Trip, and Fall Prevention: A Practical Handbook, Second Edition demonstrates how, with proper design and maintenance, many of these events can be prevented. - Falls and Related Injuries: Slips, Trips, Missteps, and Their Consequences, [Book at Amazon] Lawyers & Judges Publishing, (June 2002), ISBN-10: 0913875430 ISBN-13: 978-0913875438

"Falls in the home and public places are the second leading cause of unintentional injury deaths in the United States, but are overlooked in most literature.

This book is unique in that it is entirely devoted to falls. Of use to primary care physicians, nurses, insurance adjusters, architects, writers of building codes, attorneys, or anyone who cares for the elderly, this book will tell you how, why, and when people will likely fall, what most likely will be injured, and how such injuries come about. " - Slips, Trips, Missteps and Their Consequences, [Book at Amazon] Second Edition, Gary M. Bakken, H. Harvey Cohen,A. S. Hyde, Jon R. Abele, ISBN-13: 978-1-933264-01-1 or ISBN 10: 1-933264-01-2, available from the publisher, Lawyers ^ Judges Publishing Company,Inc., www.lawyersandjudges.com sales@lawyersandjudges.com

- The Stairway Manufacturers' Association, (877) 500-5759, provides a pictorial guide to the stair and railing portion of the International Residential Code. [copy on file as http://www.stairways.org/pdf/2006%20Stair%20IRC%20SCREEN.pdf ] -

- Slips, Trips, Missteps and Their Consequences, [Book at Amazon] Second Edition, Gary M. Bakken, H. Harvey Cohen,A. S. Hyde, Jon R. Abele, ISBN-13: 978-1-933264-01-1 or ISBN 10: 1-933264-01-2, available from the publisher, Lawyers & Judges Publishing

- Templer, J.A. (1992). The staircase: Vol. 2, studies of hazards, falls, and safer design. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. 147-149.

- VandenBussche, Jessica, Kaitlin M. Gallagher, Jason Young, Rob J. Parkinson, and Jack P. Callaghan. "Foot placement in oblique stair descent." In Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, vol. 55, no. 1, pp. 1765-1768. Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2011.

Abstract:

Extensive research has been conducted on stair safety as a loss of balance due to a misplaced step on a stair can result in a fall and serious injury. One aspect of stair safety that has not been well studied is oblique (angled) stair descent/ascent. Since oblique stair geometry affects the distance travelled and the theoretical symmetry of one’s stance, there are potential implications for fall risk.

The purpose of this study was to investigate whether there are adaptations in foot placement that pedestrians demonstrate when descending stairs at oblique angles. Sixteen participants descended steps along two paths – 0 and 45 degrees. Kinematic data of the lower limbs were collected to calculate average step length, average step width, and toe placement.

The data suggest that pedestrians compensate for angled descent by narrowing their step width and using a biased foot placement relative to the step edges, such that the inside foot (the foot furthest from the flared side) lands further forward on the step than the outside foot (the foot closest to the flared side).

These variations from straight stair descent provide a more symmetric stance for oblique stair descent and may reflect adaptations to reduce the risk of a misstep.

CONTACT US to contribute images of other types of unsafe stairs or railings. Contributors who wish to remain anonymous may do so. See our PRIVACY POLICY - InspectApedia.com.

Question: Someone fell down the stairs when the rail bracket came out of the wall. Is the landlord responsible?

There is a lease provision requiring out of possession land-lord to do structural repairs. Several years before an accident a new stairway was constructed in a building between the main level and basement level. including required handrail.

While using the steps, someone fell the 12 stairs when the bracket holding the upper left handrail came out of the wall. Was the landlord responsible for this failure; i.e. is a hand-rail part of land-lords requirement to make structural repairs, keeping in mind that the landlord paid for and hired the contractor to install the hand-rail. - R.S. 8/2/12

Reply:

A competent onsite inspection by an expert usually finds additional clues that help accurately diagnose a problem with stairs, railings, and other conditions that can cause or contribute to a fall - not something I can assess by a brief email text message. That said, here are some things to consider:

- the affixing of responsibility for steps, rails, maintenance, and installation details is a legal question for the attorneys and code officials in your city and on the case

- in my OPINION in general a property owner is expected to provide safe steps and railings. That responsibility may or may not be spelled out in your property lease under the legal definitions of safe or habitable - questions for an attorney

- around stair fall cases there is often considerable argument about who was responsible for what, including an argument about use of the word "structural"

In my OPINION stairs form an integral and critical part of a structure as obviously one cannot access certain areas without them.

But beware that a strict engineering definition of "structure" pertains to supporting elements of a building, not its stairs (except for their own structural support - which can be adequate while stairs and rails may still be unsafe and improper).

So the use of the term structural is one that, when spoken or written without care, can cause trouble for everybody. For example, in a proper or engineering sense, a handrailing is not a structural component of a building. It is not holding the building up. To be perfectly clear, a handrailing is part (a component) of the structure, but it is not structural.

Question: stair by elevator

(Feb 3, 2013) Randy Knudson said:

I need some help finding Building codes or other standards which address the obvious hazard of having an elevator door opening, directly adjacent on the left hand side to an open stairwell. There is seven inches from the door opening to the first step. This is a public building.

Reply:

Randy

Because the number of creative building construction details that builders and designers can devise is essentially infinite, I'm doubtful that one can find an explicit code prohibition for each of them, including the case you cite.

Nor is the hazard as obvious to me as to you. When closed the elevator door is essentially the same barrier as a wall. When the elevator door is open its walking surface extends first into the hallway in the direction of travel - across the width of the hall. A walker then has to make a turn to their left to enter the stairwell. Why is this different from turning to the left when walking down a corridor to enter a stair?

However, when you ask your local building code compliance inspector to take a look at the situation you describe, if she agrees that it's hazardous that person's opinion has force of law. She (or he) may cite a more general code provision as supporting that view, but as you may know, it's the local building official whose judgment, on-site, that's the final authority.

Question: obstructions and/or retail displays positioned at the top of short-flight stairs

(June 24, 2015) Maryland said:

What section would discuss short-flight stairs in shopping malls?

What section would discuss obstructions and/or retail displays positioned at the top of short-flight stairs in shopping malls?

Reply:

Maryland

I don't find portable obstructions that may be a slip trip fall hazard at stairs something discussed in the stair codes themselves but that's certainly an important topic in stair safety. There are requirements to keep obstructions off of the stairway itself, for example in fire stairs and emergency exit stairways.

Short stair flights must be built to the same rise, run, specs as longer runs of stairs and can present similar trip hazards. The requirement for handrailings on short stairs varies by jurisdiction and is discussed in our Handrails section - see the ARTICLE INDEX given above.

Research on short flight stairs, stairway obstructions, retail spaces

- Kaufmann, Michael. "Reducing Slip, Trip and Fall Accidents on Walkways and Stairs." In ASSE Professional Development Conference. American Society of Safety Engineers, 2007.

- Marietta, William. "Trip, slip and fall prevention." The Work Environment. Occupational Health Fundamentals. Lewis Publishers, inc. Michigan (1991): 241-276.

- Natalizia, David M. "Avoiding 12 Common Mistakes In Slip, Trip, And Fall Prevention." In ASSE Professional Development Conference and Exhibition. American Society of Safety Engineers, 2009.

Roys, Mike. "Steps and stairs." Understanding and Preventing Falls: An Ergonomics Approach (2005): 42.

...

Continue reading at SLIP TRIP & FALL HAZARD LIST, STAIRS, FLOORS, WALKS or select a topic from the closely-related articles below, or see the complete ARTICLE INDEX.

Or see STAIR CODES & STANDARDS - downloads

Or see these

Stair Fall Hazard Articles

- ACCESSIBLE DESIGN

- ADA STAIR & RAIL SPECIFICATIONS

- GUARDRAILS DEFECTIVE or MISSING

- HANDRAILS & HANDRAILINGS

- HALTING WALK STAIR DESIGNS for LOW SLOPES or SHORT STEP RISE

- SLIP TRIP & FALL HAZARD LIST, STAIRS, FLOORS, WALKS - master list

- STAIR CONSTRUCTION IDEAL DIMENSIONS

- STAIR DESIGN for SENIORS

- STAIR DESIGNS for UNEVEN / SLOPED SURFACES

- STAIR DIMENSIONS, WIDTH, HEIGHT

- STAIR PLATFORMS & LANDINGS, ENTRY

- STAIR RAILS, STAIR GUARDS

- STAIR TREAD NOSE SPECIFICATIONS

- STAIR USER FOOT & HAND PLACEMENT

- STAIRWAY CHAIR LIFTS

Suggested citation for this web page

STAIR USER FOOT & HAND PLACEMENT at InspectApedia.com - online encyclopedia of building & environmental inspection, testing, diagnosis, repair, & problem prevention advice.

Or see this

INDEX to RELATED ARTICLES: ARTICLE INDEX to STAIRS RAILINGS LANDINGS RAMPS

Or use the SEARCH BOX found below to Ask a Question or Search InspectApedia

Ask a Question or Search InspectApedia

Try the search box just below, or if you prefer, post a question or comment in the Comments box below and we will respond promptly.

Search the InspectApedia website

Note: appearance of your Comment below may be delayed: if your comment contains an image, photograph, web link, or text that looks to the software as if it might be a web link, your posting will appear after it has been approved by a moderator. Apologies for the delay.

Only one image can be added per comment but you can post as many comments, and therefore images, as you like.

You will not receive a notification when a response to your question has been posted.

Please bookmark this page to make it easy for you to check back for our response.

IF above you see "Comment Form is loading comments..." then COMMENT BOX - countable.ca / bawkbox.com IS NOT WORKING.

In any case you are welcome to send an email directly to us at InspectApedia.com at editor@inspectApedia.com

We'll reply to you directly. Please help us help you by noting, in your email, the URL of the InspectApedia page where you wanted to comment.

Citations & References

In addition to any citations in the article above, a full list is available on request.

- [2] Stair Construction Requirements for Residential Decks, 2007 California Building Code, 1009.3 and 1013.2, Mono County Community Building Department, POB 347, Mammoth Lakes CA 93546, 760-924-1800, web search 12/25/11, original source: monocounty.ca.gov/cdd%20site/Building/documents/MonoCountyRes-DeckStairConstr.pdf

- [3] CHAPTER 5: GENERAL SITE AND BUILDING ELEMENTS, original source: access-board.gov/ada-aba/comparison/chapter5.htm

- [4] Stephenson, Elliott O., THE ELIMINATION OF UNSAFE GUARDRAILS, A PROGRESS REPORT [PDF] Building Standards, March-April 1993

- [5] "Are Functional Handrails Within Our Grasp" Jake Pauls, Building Standards, January-February 1991

- Steps and Stairways, Cleo Baldon & Ib Melchior, Rizzoli, 1989.

- "The Dimensions of Stairs", J. M. Fitch et al., Scientific American, October 1974.

- Our recommended books about building & mechanical systems design, inspection, problem diagnosis, and repair, and about indoor environment and IAQ testing, diagnosis, and cleanup are at the InspectAPedia Bookstore. Also see our Book Reviews - InspectAPedia.

- Best Practices Guide to Residential Construction, by Steven Bliss. John Wiley & Sons, 2006. ISBN-10: 0471648361, ISBN-13: 978-0471648369, Hardcover: 320 pages, available from Amazon.com and also Wiley.com. See our book review of this publication.

- Decks and Porches, the JLC Guide to, Best Practices for Outdoor Spaces, Steve Bliss (Editor), The Journal of Light Construction, Williston VT, 2010 ISBN 10: 1-928580-42-4, ISBN 13: 978-1-928580-42-3, available from Amazon.com

- Building Research Council, BRC, nee Small Homes Council, SHC, School of Architecture, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, brc.arch.uiuc.edu. "The Small Homes Council (our original name) was organized in 1944 during the war at the request of the President of the University of Illinois to consider the role of the university in meeting the demand for housing in the United States. Soldiers would be coming home after the war and would be needing good low-cost housing. ... In 1993, the Council became part of the School of Architecture, and since then has been known as the School of Architecture-Building Research Council. ... The Council's researchers answered many critical questions that would affect the quality of the nation's housing stock.

- How could homes be designed and built more efficiently?

- What kinds of construction and production techniques worked well and which did not?

- How did people use different kinds of spaces in their homes?

- What roles did community planning, zoning, and interior design play in how neighborhoods worked

- In addition to citations & references found in this article, see the research citations given at the end of the related articles found at our suggested

CONTINUE READING or RECOMMENDED ARTICLES.

- Carson, Dunlop & Associates Ltd., 120 Carlton Street Suite 407, Toronto ON M5A 4K2. Tel: (416) 964-9415 1-800-268-7070 Email: info@carsondunlop.com. Alan Carson is a past president of ASHI, the American Society of Home Inspectors.

Thanks to Alan Carson and Bob Dunlop, for permission for InspectAPedia to use text excerpts from The HOME REFERENCE BOOK - the Encyclopedia of Homes and to use illustrations from The ILLUSTRATED HOME .

Carson Dunlop Associates provides extensive home inspection education and report writing material. In gratitude we provide links to tsome Carson Dunlop Associates products and services.