The Nature of Vision

The Nature of Vision

Inspecting Complex Systems, Why We See or Do Not See Things We Are Looking For - Or Should Be Looking For

- POST a QUESTION or COMMENT about the nature of vision, types of blindness, and visual or perception errors during building or enviornmental inspections

Visual perception errors in building, environmental & forensic investigations: this article discusses errors in visual perception during examination of complex systems and structures such as buildings or mechanical systems.

The purpose of this article is to improve the chances that any inspector of any complex system, charged with the visual examination of the system will find both the visually apparent and the visually present but more subtle clues which signal important costly repairs, unsafe conditions, or other targets of the inspection.

Most people believe that if our eyes are open, we are seeing. Cognitive scientists once thought our visual perception acted much like a videotape recorder. We know now that this is not the case. Perception studies are demonstrating how little people actually see when they are not paying attention.1.

InspectAPedia tolerates no conflicts of interest. We have no relationship with advertisers, products, or services discussed at this website.

- Daniel Friedman, Publisher/Editor/Author - See WHO ARE WE?

Surprises in the Study of Vision and Inspection of Buildings or Other Complex Systems

Study in a variety of fields (eye and brain, the psychology of error, the

physics of light and optics, microscopy, and aerobiology) has led to some

surprises and to recognition that forensic experts and inspectors should not be

overconfident in their ability to "see" what they are looking "for." Even the

ability to see what we are looking "at" is demonstrated to be incomplete.

Study in a variety of fields (eye and brain, the psychology of error, the

physics of light and optics, microscopy, and aerobiology) has led to some

surprises and to recognition that forensic experts and inspectors should not be

overconfident in their ability to "see" what they are looking "for." Even the

ability to see what we are looking "at" is demonstrated to be incomplete.

"Inspection" as used here refers to a primarily-visual approach which may make limited use of special equipment such as moisture meters or electrical circuit polarity testers, but which does not involve demolition or similar "invasive" methods to evaluate the condition of a building or similar complex system and its subsystems such as building mechanicals.

Photo above: sample from the 9/11 World Trade Center disaster dust processed in our forensic lab. As un-founded conspiracy theories abounded following the WTC collapse, reputable government and private independent forensic labs confirmed the types of materials present in the dust and also found no evidence of of explosives or explosive devices.

Article Contents

Research on Vision Can Inform Inspectors of Complex Systems, Machines, Buildings, etc.

This article is a chapter in the authors "Developing your X-Ray Vision, A Promotion Theory for Forensic Observation of Residential Construction - Levels of Fear, and how to use them to find and report significant, hidden problems."

See https://InspectAPedia.com/vision/Visual_Perception_Errors.php - The Nature of Vision - inspecting complex systems (this article, online) and

see https://InspectAPedia.com/home_inspection/Building_Inspection_Techniques.php for the online version of "Developing your X-Ray Vision." As this is an ongoing study project these articles are updated periodically.

Also see LIGHT, GUIDE to FORENSIC USE and

see https://InspectAPedia.com/vision/Sinkholes_Subsidences.php about sinkholes in Florida.

Also see InspectAPedia.com for free in-depth research on building defect recognition and repair, including both physical defects on buildings and environmental concerns such as mold and allergens.

Several areas of research can inform forensic inspectors and may improve their ability to recognize, record, and thus act on defects:

- Neurology and brain function, particularly with respect to "seeing"

- Physics and the study of light, particularly optical physics and the detection of objects, both macroscopically (by eye) and microscopically (by instrument)

- Psychology of seeing, or "not seeing," the psychology of errors - why we make mistakes or fail to recognize something important, and why we do not, indeed cannot, focus our attention so as to "see" everything that is in our visual field.

An enormous body of research pertinent to the human ability to consciously see, recognize, and record information exists among these areas. I have not attempted to recap everything about these areas, but I will cite a few ideas they suggest and which pertain to the use of an inspection methodology employing techniques to improve recognition of subtle clues of hidden defects.

What is needed in order to "see" any object or object-feature?

Presence: Information or Object Must Be Present

The object or feature must be present in the visual field of the observer so that all the observer needs to do is direct his or her eye there to be [potentially] able to see it. The size and other requisite aspects of the object or feature are discussed below.

For purposes of this discussion we refer to normal sighted-human vision, unaided by special equipment such as microscopes or telescopes, though the observer may [indeed should] make use of corrective eyeglasses or contact lenses if their vision has been found in need of those aids.

In my longer X-ray VISION article my view is that "clues" which suggest an otherwise "hidden" defect are in fact visual "features" of that very defect or condition and can so can be recognized.

Light: Light Reflects From Object to Eye

Light reflected from a surface towards the eye of an observer carries incomplete information about the object and can be distorted. In any case it will not contain all of even the surface information about the object due to limitations of illumination, optical distortion, and of course the inability to "see around corners."

The human eye is sensitive to light (electromagnetic radiation) from around 350 to 750nm in wavelength. It is speculated that we evolved to be sensitive to radiation at these wavelengths because they are so common in sunlight. Some other animals have eyes which are sensitive to electromagnetic radiation at lower wavelengths (such as infra red).

In the process of "inspecting" objects and systems in the field, inspectors use a combination of local natural light, artificial indoor lighting, and flashlights. The flashlight is a more important tool than some inspectors realize. the level or intensity of illumination, angle of illumination, and color of the light source can make the difference between a humans ability to "see" or not see a feature.

The ultimate level of detection of visual features being illuminated by light is a function of the wavelength of the light source, since particles smaller than the wavelength may fail to refract or bend the light waves sufficiently to permit detection.

In forensic microscopy the wavelength of the light source is a factor but more important is the ability of the microscopes lens system to direct light rays at the particle being examined. The particle refracts, or "bends" light rays, producing a visible image which is focused by the lens system.

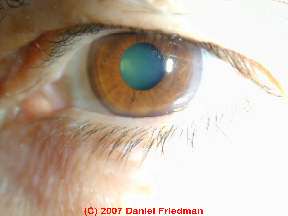

Eye: Light Reaches Eye

The eye, the cornea and lens of the eye itself is the image-forming system for human inspectors working without a microscope or binoculars.

The image of the observed object is formed at the back of the eye on the retina where special cells in turn fire neurons which pass the visual image map to the visual cortex of the brain. The human eye can resolve particles down to a few hundredths of an inch or so in diameter.

Brain: Brain Interprets Information

The brain plays a considerable additional role in "seeing" beyond mere image mapping. Additional image data processing occurs in the brain in order to recognize what is being observed.

What a human "sees" is a representation of the objective world built-up in the brain from a combination of sensory inputs and significant additional processing in the brain. While I'm taking some literary license to say so, it would appear most likely that the brain constructs the "image" in the observers consciousness from a combination of visual inputs from the eye, a map of the eyes input in the visual cortex, and processing of that data along with stored maps of "expected images."

As human brains are designed to "make sense" of various sensory inputs, we may do so even if "making sense" means "making it up." Thus our observations are vulnerable to illusion.

Inattentional Blindness: Observer (Home Inspector) Must Pay Conscious Attention

In addition to the need for an object to be observed, a light source, the observers eye and brain to form an image, vision also requires a level of attention by the observer. The eye and brain are not a video camera faithfully recording all visual data towards which aimed.

The inspector may fail to see objects even when they are present and readily apparent in the center of the visual field. Perhaps less difficult to grasp is research about forms of blindness or an inability to "see" - change blindness and inattentional blindness in particular. In the forming conscious visual information in the brain, inattentional blindness refers to an observers blindness to the presence of an object right in the visual field, even though the observer is awake and directing her eyes directly towards it.

Because "seeing" at a conscious level requires both the processing of visual signals from the eye and a processing of the input by the brain to form an "image," research has demonstrated that conscious "attention" is absolutely required to "see" anything. In other words, a person can be "looking" right at something, but if his attention is not focused there as well, he will not see it.

Perhaps not at all. [1] The observer is likely to fail to see something significant, even in the center of the visual field, if s/he is not looking for that particular thing - if its not in the observers "attention set."

Inspector learn quickly the importance of a comprehensive visual scan of everything.

An inspector won't "inspect" a room by only looking at one wall. But now we understand that merely directing the eyes at every surface may be quite insufficient.

What's tricky about this is that the inspector believes s/he has "looked-at" a surface, but may not have "attended" to it.

Photo Manipulation Experiment in Change Blindness in Home Inspection Reports

In a similar experiment I (D Friedman) provided a few clients with home inspection reports that included photographs of the homes we had inspected together. Despite spending three or four hours "looking" at a home, and in most cases despite multiple visits to the home by the clients, not one of the clients observed that the report included multiple inconsistent photographs of the front of the home.

In the first photograph I used photo-retouching software to add or delete windows from the front of the home. In the second photograph later in the report I used an un-edited photograph that accurately described the number of windows. Only when I asked clients to carefully compare the two photographs side by side did they report the difference in the number of windows presented.

The information that enters our eyes and is transmitted to our brains is not necessarily identical to the data that enters our consciousness. Experts explain that change blindness occurs at least in part because more information falls on our eyes than our brain can efficiently process. In other words, our brains discard much of the visual information that is available in order to avoid brain overload.

Keeping change blindness in mind and developing strategies for coping with this source of inaccuracy in visual awareness can help any inspector perform better.

Kristins Cards: A Demonstration of Inattentional Blindness

The ease with which IB occurs is nicely demonstrated by Kristins Cards at http://www.cs.bris.ac.uk/~cater/PhD/Magic/cardtrick.html -- UPDTATE: regrets, this website is obsolete and I have not found a current version online. I'm working on reproducing this exhibition.

I previously left the explanation of the viewers inability to "see" something important to Kristen. Because that online display has been lost, below I will explain this illusion of inattentional blindness:

This "card trick" shows a set of cards, say by projection onto a movie screen, and invites the audience to remember them, and to select ONE of the cards to pay attention to. "Pick your card and watch it" is more or less the instruction.

Then this illusion changes and displays a "new" set of cards. The audience is asked if the card they were concentrating on has "disappeared". Everyone will pretty much say yes, their card has vanished.

What most audiences fail to detect and report is that all of the cards have changed between the two displays.

Church points out that while this is an entertaining illustration, Kristin's Cards may not be the best example of inattentional blindness because we are directing the audience to attend a particular card.

Good inattentional blindness examples demonstrate that the observer(s) fail to notice changes, even substantial changes, in two successive images of the "same" scene.

Factors Affecting Inattentional Blindness

"Seeing" involves conscious mental effort and focus, a task from which observers can be distracted or which can fail due to IB. Four factors affect inattentional blindness: conspicuity [both sensory and cognitive], mental workload [too much or too little], expectation [attention set], and capacity. [Reference 5]

An inspector is more likely to see what s/he is looking for, and outside of that set, to see that which is familiar or large.

Home inspectors are not "seeing" everything that is present, even when its right in the center of their field of view.

An inspector is less likely to see something that s/he is not expecting, even if it is important and visually distinct by characteristics such as shape, color, or motion.

An inspectors "attention set" of expectations filters out other stimuli. An inspector is less likely to "see" a defect in a structure or system being examined if s/he does not already have an in-depth and visceral understanding of the construction and operation of the structure or system, leading to a broad and deep "attention set."

Change Blindness and its Effects on the Inspection of Complex Systems

Researchers in this area describes "change blindness" - the inability to "see" a component change between two rapid presentations of an image, and "inattention blindness [IB]which describes an inability to register and use visual information if attention is not properly focused. "Inattention blindness" is most pertinent to inspectors and recalls earlier work on the psychology of errors, and capture errors.

An interesting article on Change Blindness appeared in the New York Times reported on a talk by Jeremy Wolfe (Harvard Medical School, May 2008). Wolfe addressed a symposium, (held at the Italian academy for Advanced studies in America, at Columbia University) on the relationship between the themes of Art and Neuroscience, and he explained how often people "see" inaccurately.

For inspectors of complex systems (home inspectors or even more lofty space shuttle inspectors) the significance of Wolfe's report was the underscoring of the "frequent inability of our visual system to detect alterations to something staring us straight in the face."

This visual error occurs not only in small subtle details but also in significant items. Angier's article reports that the audience failed to notice entire stories disappearing from buildings!

The Natalie Angier's article and Jeremy Wolfe's presentation emphasize that change blindness is an important component of the list of caveats that face any inspector who needs to form an rapid, accurate impression of the system she is inspecting.

Wolfe defines two classes of brain information processing that control our conscious attention to details among the soup of items that appear in the visual field:

Bottom-up attentiveness: something grabs our attention, such as a moving object or a bright color against a different background. These items are usually noticed consciously.

Top-down attentiveness: the viewer makes a conscious act to attend to something in the visual field even though it is not contrasted by conditions such as color or movement.

-- "Blind to Change, Even as It Stares Us in the Face", Natalie Angier, New York Times, p. F2, 1 April 2008

Improving Vision: Tuning Up Your Ability to See During an Inspection

Improving Top-Down Attentiveness to Items in the Visual Field

In addition to taking advantage of an understanding of the mechanisms that our eyes and brain use to record and attend information (bottom-up attentiveness and top-down attentiveness for example) there is another step we can take to improve our top-down attentiveness:

Better training in content or significance recognition: It is possible that we can train ourselves to better manage what information our brains discard and what information our brains bring to consciousness by tuning our attention to details that pertain to specific needs, and by broadening our training in specific fields of diagnostic inspection so that more visual data leaps to our attention because we have learned that that data may be important for the task at hand.

Better training in attention management: because research shows (and Wolfe reports) that the human brain can only attend well to a limited number of items at a time, even simplistic mechanical or rote inspection procedures that force the inspector to spend a portion of his/her time attending to specific questions might improve inspection performance.

For example, let's not just "inspect the heating system" rather, let's "look for evidence that the chimney may be blocked, having been trained to identify a larger set of clues that can indicate that condition. (Back pressure burns on the boiler, odors, soot, stains in the living space, occupant health complaints, etc.)

A Checklist of Coping Strategies to Improve Visual Attention during Inspections

- An inspector can improve his/her ability to see. Simply realizing this fact opens the way to improvement in inspection acuity and completeness.

- Manage distractions as a cause of inattentional blindness: use coping strategies (be in control of the inspection, use both methodical and routine-breaking scanning)

- Use but limit object fixation, a cause of inattentional blindness common to inspectors [take an observation to completion and redirect attention to a new scan]

- Expand the "attention set" [know how its constructed, how it works etc.] but recognize that training has the danger of masking off the unexpected. Inattentional blindness vanishes if the observer expects the item.

- Don't assume you know it all: Minimize the danger of "being an expert" having a too-fixed set of expectations and being unable to "see" new or changed inputs occurring on old, familiar systems)

- Study the proper use of light (level of illumination, angle of illumination, reflection, resolution, color) to maximize the ability to "see"

- "Keeping fresh" as an experienced visual-inspector of complex systems

- Study new topics in new fields: forensic engineering, microscopy, yoga, Zen, [insight and attitudes about "paying attention" ]

- Inspect with another professional, comparing approaches to field work

- Invite client [or another third party] participation, inviting client questions during the process; the client, even as a non-expert, may notice and question clues that lead to something the inspector has not "seen"; even extraneous questions "off topic" can prevent an inspector from becoming too routinized in the inspection procedure

- Look for the "surprise" that is present at every building or system

- Vary the inspection routine, sequence, or other methods and tools

...

Continue reading at ADVANCED INSPECTION METHODS or select a topic from the closely-related articles below, or see the complete ARTICLE INDEX.

Or see these

Recommended Articles

- ADVANCED INSPECTION METHODS

- ENVIRO-SCARE - PUBLIC FEAR CYCLES

- FEAR-O-METER: Dan's 3 D's SET REPAIR PRIORITIES

- HOME INSPECTION ADVANCED TOPICS

- WTC DUST PARTICLE - MICRO PHOTOGRAPHS

Suggested citation for this web page

VISUAL PERCEPTION ERRORS at InspectApedia.com - online encyclopedia of building & environmental inspection, testing, diagnosis, repair, & problem prevention advice.

Or see this

INDEX to RELATED ARTICLES: ARTICLE INDEX to BUILDING & HOME INSPECTION

Or use the SEARCH BOX found below to Ask a Question or Search InspectApedia

Ask a Question or Search InspectApedia

Questions & answers or comments about the nature of vision, types of blindness, and visual or perception errors during building or enviornmental inspections.

Try the search box just below, or if you prefer, post a question or comment in the Comments box below and we will respond promptly.

Search the InspectApedia website

Note: appearance of your Comment below may be delayed: if your comment contains an image, photograph, web link, or text that looks to the software as if it might be a web link, your posting will appear after it has been approved by a moderator. Apologies for the delay.

Only one image can be added per comment but you can post as many comments, and therefore images, as you like.

You will not receive a notification when a response to your question has been posted.

Please bookmark this page to make it easy for you to check back for our response.

IF above you see "Comment Form is loading comments..." then COMMENT BOX - countable.ca / bawkbox.com IS NOT WORKING.

In any case you are welcome to send an email directly to us at InspectApedia.com at editor@inspectApedia.com

We'll reply to you directly. Please help us help you by noting, in your email, the URL of the InspectApedia page where you wanted to comment.

Citations & References

In addition to any citations in the article above, a full list is available on request.

- Daniel Friedman - principal author/editor of the InspectAPedia® Website

- Jennifer Church, Vassar College, Poughkeepsie, NY, Personal communication, Jennifer Church, 15 July 2008 regarding change blindness and coping strategies.

- Thanks to Alan Carson and Bob Dunlop, Carson Dunlop, Associates, Toronto, for discussion and review of this topic.

- "Blind to Change, Even as It Stares Us in the Face", Natalie Angier, New York Times, p. F2, 1 April 2008

References: Vision, Seeing, and Inattentional Blindness

- "A Neurobiologists Notebook: The Minds Eye, what the blind see," Oliver Sacks, New Yorker Magazine, July 28, 2003 p. 46-59 [Three different responses to "blindness," increased-detailed visual mapping in some "blind" individuals, synthesia]

- "An Overview and Some Applications of Inattentional Blindness Research," Todd A. Ward, http://hubel.sfasu.edu/courseinfo/SL03/inattentional_blindness.htm Austin State University

- "Inattentional Blindness Versus Inattentional Amnesia for Fixated but Ignored Words," Geraint Rees, Charlotte Russell, Christopher D. Frith, Jon Drier, Science, 24 December 1999www.sciencemag.org

- "Inattentional Blindness, An Overview," Arian Mack & Irvin Rock, http://psyche.cs.monash.edu.au/v5/psyche-5-03-mack.html

- "Inattentional Blindness" & Conspicuity," Mark Green, http://www.visualexpert.com/Resources/inattentionalblindness.html

- "Seeing Reasons," Jennifer Church, Vassar College, Poughkeepsie, NY, ACLS Project Proposal, 2003.

- "When Good Observers Go Bad: Change Blindness, Inattentional Blindness,

and Visual Experience," http://cogprints.ecs.soton.ac.uk/archive/00001050/ - abstract

http://psyche.cs.monash.edu.au/v6/psyche-6-09-rensink.html - article full text - Eye and Brain, the Psychology of Seeing, Richard L. Gregory, 5th Ed, Princeton University Press 1997, ISBN 0-691-04837-1 (See Ch. 8, "Learning how to see")

- Inattentional Blindness, Arien Mack and Irvin Rock, MIT Press, 2000 ISBN 0-262-13339-3

- Light, Michael I. Sobel, University of Chicago Press 1987, ISBN 0-226-76751-5

- The Astonishing Hypothesis, the Scientific Search for the Soul, Francis Crick, Touchstone, Simon & Schuster 1994, ISBN 0-684-80158-2 (See Chapter 4, "The Psychology of Vision", 14 "Visual Awareness")

- The Nature of Visual Illusion, Mark Fineman, Dover Publications 1996 (original 1981), ISBN 0-486-29105-7

- The Quest for Consciousness, a Neurobiological Approach, Christof Koch, Roberts & Co. 2004, ISBN 0-9747077-8-0 (exploration of seeing, visual processes, consciousness)

- Visual Cognition Lab video demos and stimuli at http://viscog.beckman.uiuc.edu/djs_lab/demos.html

[1] Ward points out [Reference 2] that "Most people believe that if our eyes are open, we are seeing. Cognitive scientists once thought our visual perception acted much like a videotape recorder. We know now that this is not the case. perception studies are demonstrating how little people actually see when they are not paying attention. Inattentional blindness refers to a situation in which a stimulus that is not attended is not perceived, even though a person is looking directly at it.

Mack and Rock found that a puzzling and surprising aspect of all the experiments examining the perception of a small number of critical stimuli under conditions of inattention was that, on average, 25% of the observers failed to detect their presence"" leading to a paradox that "in order to see something with any detail in the environment, observers must first direct their attention towards an object. However if something is not yet perceived, how can observers direct their attention towards it?" Part of the answer lies in the observation that we perceive more than we notice. Driving is an example. So we do perceive environmental stimuli outside of our awareness. The paradox falls apart when one distinguishes between conscious, attended stimuli and unconscious, unattended stimuli.

What characteristics determine which environmental stimuli are attended and thus consciously perceived? Conspicuity. "Blindness" to visual stimuli may occur, then because they lack conspicuity. But such blindness can also occur when the observer is focusing on something else, (distraction or a capture error) even though the stimuli are right there in the center of his/her field of vision! Such blindness can also occur from too little mental activity, such as performing a task by rote.

An observer can be blind to even conspicuous stimuli if s/he is not expecting it. Navy pilots in training failed to see a large airplane set on the carrier deck in the landing zone just before touchdown. "When an observer has an attentional set for an object or for certain characteristics of objects, only things in the attentional set will capture their attention when presented in the perceptual field." Similarly, observers were more likely to notice an unexpected object if it was more similar to the stimuli they were currently attending.

Other references for inattentional blindness

- Stanislas Dehaene and Jean-Pierre Changeux. Ongoing spontaneous activity controls access to consciousness: a neuronal model for inattentional blindness.. PLoS Biol, 3(5):e141, May 2005.

Abstract: Even in the absence of sensory inputs, cortical and thalamic neurons can show structured patterns of ongoing spontaneous activity, whose origins and functional significance are not well understood. We use computer simulations to explore the conditions under which spontaneous activity emerges from a simplified model of multiple interconnected thalamocortical columns linked by long-range, top-down excitatory axons, and to examine its interactions with stimulus-induced activation. Simulations help characterize two main states of activity. First, spontaneous gamma-band oscillations emerge at a precise threshold controlled by ascending neuromodulator systems. Second, within a spontaneously active network, we observe the sudden "ignition" of one out of many possible coherent states of high-level activity amidst cortical neurons with long-distance projections. During such an ignited state, spontaneous activity can block external sensory processing. We relate those properties to experimental observations on the neural bases of endogenous states of consciousness, and particularly the blocking of access to consciousness that occurs in the psychophysical phenomenon of "inattentional blindness," in which normal subjects intensely engaged in mental activity fail to notice salient but irrelevant sensory stimuli. Although highly simplified, the generic properties of a minimal network may help clarify some of the basic cerebral phenomena underlying the autonomy of consciousness. - Lionel Naccache, Stanislas Dehaene, Laurent Cohen, Marie-Odile Habert, Elodie Guichart-Gomez, Damien Galanaud, and Jean-Claude Willer. Effortless control: executive attention and conscious feeling of mental effort are dissociable.. Neuropsychologia, 43(9):1318-1328, 2005.

Abstract: Recruitment of executive attention is normally associated to a subjective feeling of mental effort. Here we investigate the nature of this coupling in a patient with a left mesio-frontal cortex lesion including the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), and in a group of comparison subjects using a Stroop paradigm. We show that in normal subjects, subjective increases in effort associated with executive control correlate with higher skin-conductance responses (SCRs). However, our patient experienced no conscious feeling of mental effort and showed no SCR, in spite of exhibiting normal executive control, and residual right anterior cingulate activity measured with event-related potentials (ERPs). Finally, this patient demonstrated a pattern of impaired behavior and SCRs in the Iowa gambling task-elaborated by Damasio, Bechara and colleagues-replicating the findings reported by these authors for other patients with mesio-frontal lesions. Taken together, these results call for a theoretical refinement by revealing a decoupling between conscious cognitive control and consciously reportable feelings. Moreover, they reveal a fundamental distinction, observed here within the same patient, between the cognitive operations which are depending on normal somatic marker processing, and those which are withstanding to impairments of this system. - Claire Sergent, Sylvain Baillet, and Stanislas Dehaene. Timing of the brain events underlying access to consciousness during the attentional blink.. Nat Neurosci, September 2005.

Abstract: In the phenomenon of attentional blink, identical visual stimuli are sometimes fully perceived and sometimes not detected at all. This phenomenon thus provides an optimal situation to study the fate of stimuli not consciously perceived and the differences between conscious and nonconscious processing. We correlated behavioral visibility ratings and recordings of event-related potentials to study the temporal dynamics of access to consciousness. Intact early potentials (P1 and N1) were evoked by unseen words, suggesting that these brain events are not the primary correlates of conscious perception. However, we observed a rapid divergence around 270 ms, after which several brain events were evoked solely by seen words. Thus, we suggest that the transition toward access to consciousness relates to the optional triggering of a late wave of activation that spreads through a distributed network of cortical association areas. - Mariano Sigman, Hong Pan, Yihong Yan, Emily Stern, David Silbersweig, and Charles Gilbert. Top-Down reorganization of activity in the visual pathway after learning a shape identification task.. Neuron, 46(5):823-835, 2005. [PDF] [bibtex-entry]

- Stanislas Dehaene, Jean-René Duhamel, Marc D. Hauser, and Giacomo Rizzolatti. From Monkey Brain to Human Brain. A Fyssen Foundation Symposium.. MIT Press, 2005

- Claire Sergent. Dynamique de l'accès à la conscience : caractérisation comportementale et bases neurales de l'accès à la conscience lors du clignement attentionnel (attentional blink). Thesis/Dissertation, Université Paris XI, 2005.

- Valérie Ventureyra. À la recherche de la langue perdue: étude psycholinguistique de l'attrition de la première langue chez des cor'eens adoptés en France. Thesis/Dissertation, École des hautes études en sciences sociales, Paris, January 2005.

- SCSMI: Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image. Kristin Thompson, Observations on film art

- Our recommended books about building & mechanical systems design, inspection, problem diagnosis, and repair, and about indoor environment and IAQ testing, diagnosis, and cleanup are at the InspectAPedia Bookstore. Also see our Book Reviews - InspectAPedia.

- Building Pathology, Deterioration, Diagnostics, and Intervention, Samuel Y. Harris, P.E., AIA, Esq., ISBN 0-471-33172-4, John Wiley & Sons, 2001 [General building science-DF] ISBN-10: 0471331724 ISBN-13: 978-0471331728

- Diagnosing & Repairing House Structure Problems, Edgar O. Seaquist, McGraw Hill, 1980 ISBN 0-07-056013-7 (obsolete, incomplete, missing most diagnosis steps, but very good reading; out of print but used copies are available at Amazon.com, and reprints are available from some inspection tool suppliers). Ed Seaquist was among the first speakers invited to a series of educational conferences organized by D Friedman for ASHI, the American Society of Home Inspectors, where the topic of inspecting the in-service condition of building structures was first addressed.

- Building Failures, Diagnosis & Avoidance, 2d Ed., W.H. Ransom, E.& F. Spon, New York, 1987 ISBN 0-419-14270-3

- Domestic Building Surveys, Andrew R. Williams, Kindle book, Amazon.com

- Defects and Deterioration in Buildings: A Practical Guide to the Science and Technology of Material Failure, Barry Richardson, Spon Press; 2d Ed (2001), ISBN-10: 041925210X, ISBN-13: 978-0419252108. Quoting:

A professional reference designed to assist surveyors, engineers, architects and contractors in diagnosing existing problems and avoiding them in new buildings. Fully revised and updated, this edition, in new clearer format, covers developments in building defects, and problems such as sick building syndrome. Well liked for its mixture of theory and practice the new edition will complement Hinks and Cook's student textbook on defects at the practitioner level. - Guide to Domestic Building Surveys, Jack Bower, Butterworth Architecture, London, 1988, ISBN 0-408-50000 X

- "Avoiding Foundation Failures," Robert Marshall, Journal of Light Construction, July, 1996 (Highly recommend this article-DF)

- "A Foundation for Unstable Soils," Harris Hyman, P.E., Journal of Light Construction, May 1995

- "Inspecting Block Foundations," Donald V. Cohen, P.E., ASHI Reporter, December 1998. This article in turn cites the Fine Homebuilding article noted below.

- "When Block Foundations go Bad," Fine Homebuilding, June/July 1998

- Natural Ventilation for Buildings, U.S. Department of Energy

- R-Value of Wood, U.S. Department of Energy

- Spot Ventilation for houses, U.S. Department of Energy

- Slab on Grade Foundation Moisture and Air Leakage, U.S. Department of Energy

- Straw Bale Home Design, U.S. Department of Energy provides information on strawbale home construction - original source at http://www.energysavers.gov/your_home/designing_remodeling/index.cfm/mytopic=10350

- In addition to citations & references found in this article, see the research citations given at the end of the related articles found at our suggested

CONTINUE READING or RECOMMENDED ARTICLES. - "A Hole in the Ground Erupts, to Estonia's Delight", New York Times, 9 December 2008 p. 10.

- History of water usage in Estonia: (5.7 MB PDF) jaagupi.parnu.ee/freshwater/doc/the_history_of_water_usage_systems_in_estonia.pdf

- "Quebec Family Dies as Home Vanishes Into Crater, in Reminder of Hidden Menace", Ian Austen, New York Times, 13 May 2010 p. A8. See http://www.nytimes.com/

- "Quick Clay", Wikipedia search 5/13/2010 - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quick_clay

- Florida DEP - Department of Environmental Protection, & Florida Geological survey (http://www.dep.state.fl.us/geology/default.htm) on Florida sinkholes: Effects of Sinkholes on Water Conditions Hernando County, Florida, Brett Buff, GIS in Water Resources, 2008, Dr. David R. Maidment, Photos - Tom Scott, Florida Geographic Survey - Web Search 06/09/2010 - http://www.dep.state.fl.us/geology/geologictopics/jacksonsink.htm

and - http://www.dep.state.fl.us/geology/geologictopics/sinkhole.htm

also see

Lane, Ed, 1986, Karst in Florida: Florida Geological Survey Special Publication 29, 100 p. - Foundation Engineering Problems and Hazards in Karst Terranes, James P. Reger, Maryland Geological Survey, web search 06/05/2010, original source: http://www.mgs.md.gov/esic/fs/fs11.html

Maryland Geological Survey, 2300 St. Paul Street, Baltimore, MD 21218 - "Frost Heaving Forces in Leda Clay", Penner, E., Division of Building Research, National Research Council of Canada, Canadian Geotechnical Journal, NRC Research Press, 1970-2, Vol 7, No 1, PP 8-16, National Research Council of Canada, Accession number 1970-023601, .

- "Geoscape Ottowa-Gatineau Landslides", Canada Department of Natural Resources, original source http://geoscape.nrcan.gc.ca/ottawa/landslides_e.php

- Kochanov, W. E., 1999, Sinkholes in Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania

Geological Survey, 4th ser., Educational Series 11, 33 p., 3rd printing April 2005, Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources / Bureau of Topographic and Geologic Survey, DCNR Educational Series 11, Pennsylvania Geological Survey, Fourth Series, Harrisburg,

1999 - web search 06/05/2010, original source: http://www.dcnr.state.pa.us/topogeo/hazards/es11.pdf - [1] Sarah Cervone, [web page] data from the APIRS database, Graphics by Ann Murray, Sara Reinhart and Vic Ramey, Vic Ramey is the editor. DEP review by Jeff Schardt and Judy Ludlow. The web page is a collaboration of the Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants, University of Florida, and the Bureau of Invasive Plant Management, Florida Department of Environmental Protection contact: varamey@nersp.nerdc.ufl.edu [A primary resource for this article

- [2] Center for Cave and Karst Studies or the Kentucky Climate Center, both at Western Kentucky University

- Vanity Fair - web search 06/04/2010 http://www.vanityfair.com/online/daily/2010/06/what-caused-the-guatemala-sinkhole-and-why-is-it-so-round.html

- Sinkholes, [on file as /vision/Sinkholes_Virginia_DME.pdf ] - , Virginia Division of Mineral Resources,

- Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy, www.dmme.virginia.gov Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy Division of Mineral Resources 900 Natural Resources Drive, Suite 500 Charlottesville, VA 22903 Sales Office: (434) 951-6341 FAX : (434) 951-6365 Geologic Information: (434) 951-6342 http://www.dmme.virginia.gov/ divisionmineralresources.shtml - Web search 06/09/2010

- Wikipedia - web search 06/04/2010 - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guatemala_City

- Newton, J. G., 1987, Development of sinkholes resulting from man's activities in the eastern United States: US Geological Survey Circular 968, 54 p.

- White, W. B., 1988, Geomorphology and Hydrology of Karst Terrains: Oxford University Press, New York, 464 p.

- Tony Waltham, F. B. (2005). Sinkholes and Subsidence, Karst and Cavernous Rocks in Engineering and Construction. Chichester, United Kingdom: Praxis Publishing.

- #3. Detecting Sinkholes with Geophysics, Enviroscan, Inc., Lancaster PA 717-396-8922 email@enviroscan.com www.enviroscan.com 2003

- In addition to citations & references found in this article, see the research citations given at the end of the related articles found at our suggested

CONTINUE READING or RECOMMENDED ARTICLES.

- Carson, Dunlop & Associates Ltd., 120 Carlton Street Suite 407, Toronto ON M5A 4K2. Tel: (416) 964-9415 1-800-268-7070 Email: info@carsondunlop.com. Alan Carson is a past president of ASHI, the American Society of Home Inspectors.

Thanks to Alan Carson and Bob Dunlop, for permission for InspectAPedia to use text excerpts from The HOME REFERENCE BOOK - the Encyclopedia of Homes and to use illustrations from The ILLUSTRATED HOME .

Carson Dunlop Associates provides extensive home inspection education and report writing material. In gratitude we provide links to tsome Carson Dunlop Associates products and services.