Definition & Types of Passive Solar Gain

Definition & Types of Passive Solar Gain

Solar Gain

& SHGC Definition, Explanation & Design Details

- POST a QUESTION or COMMENT about passive solar gain in or at buildings

- Solar design handbook questions and answers about passive soalr gain

Definition & uses of passive solar gain for heating homes.

Our page top photo illustrates a simple method for controlling passive solar gain through South facing windows and sliding glass doors and into a ceramic tile floor on a concrete slab.

The movable Japanese-style screens are hung from pegs and can be moved or relocated depending on the amount of solar gain desired.

The original design for this home was intended to use exterior solar shading but that feature was omitted during construction in the 1960's.

This article includes adaptations from U.S. DOE publications about passive solar design.[1]

InspectAPedia tolerates no conflicts of interest. We have no relationship with advertisers, products, or services discussed at this website.

- Daniel Friedman, Publisher/Editor/Author - See WHO ARE WE?

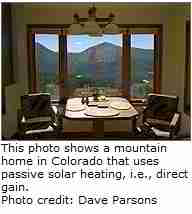

Definition of Direct Solar Gain

Direct gain is the simplest passive solar home design technique.

Direct gain is the simplest passive solar home design technique.

Sunlight enters the house through the aperture (collector)—usually south-facing windows with a glazing material made of transparent or translucent glass.

The sunlight then strikes masonry floors and/or walls, which absorb and store the solar heat.

The surfaces of these masonry floors and walls are typically a dark color because dark colors usually absorb more heat than light colors.

At night, as the room cools, the heat stored in the thermal mass convects and radiates into the room.

[Another example of direct solar gain is at our page top photo.- DF]

Some builders and homeowners have used water-filled containers located inside the living space to absorb and store solar heat.

Water stores twice as much heat as masonry materials per cubic foot of volume. Unlike masonry, water doesn't support itself.

Water thermal storage, therefore, requires carefully designed structural support.

Also, water tanks require some minimal maintenance, including periodic (yearly) water treatment to prevent microbial growth.

The amount of passive solar (sometimes called the passive solar fraction) depends on the area of glazing and the amount of thermal mass.

The amount of passive solar (sometimes called the passive solar fraction) depends on the area of glazing and the amount of thermal mass.

The glazing area determines how much solar heat can be collected. And the amount of thermal mass determines how much of that heat can be stored.

It is possible to undersize the thermal mass, which results in the house overheating.

There is a diminishing return on over sizing thermal mass, but excess mass will not hurt the performance.

The ideal ratio of thermal mass to glazing varies by climate.

Our photo (left) shows a small area designed for both direct solar gain and a brick on concrete floor providing thermal mass at a New York home.

Another important thing to remember is that the thermal mass must be insulated from the outside temperature. If the thermal mass is not insulated, the collected solar heat can drain away rapidly.

Loss of heat is especially likely when the thermal mass is directly connected to the ground or is in contact with outside air at a lower temperature than the desired temperature of the mass.

Even if you simply have a conventional home with south-facing windows without thermal mass, you probably still have some passive solar heating potential (this is often called solar-tempering).

To use it to your best advantage, keep windows clean and install window treatments that enhance passive solar heating, reduce nighttime heat loss, and prevent summer overheating.

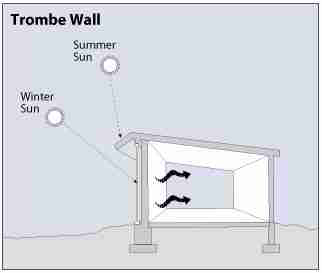

Definition of Indirect Solar Gain (Trombe Walls)

An indirect-gain passive solar home has its thermal storage between the south-facing windows and the living spaces.

An indirect-gain passive solar home has its thermal storage between the south-facing windows and the living spaces.

Illustration of a Trombe wall (left) U.S. DOE.

Using a Trombe wall is the most common indirect-gain approach. The wall consists of an 8–16 inch-thick masonry wall on the south side of a house. A single or double layer of glass is mounted about 1 inch or less in front of the wall's surface.

Solar heat is absorbed by the wall's dark-colored outside surface and stored in the wall's mass, where it radiates into the living space.

The Trombe wall distributes or releases heat into the home over a period of several hours.

Solar heat migrates through the wall, reaching its rear surface in the late afternoon or early evening. When the indoor temperature falls below that of the wall's surface, heat begins to radiate and transfer into the room.

For example, heat travels through a masonry wall at an average rate of 1 hour per inch. Therefore, the heat absorbed on the outside of an 8-inch-thick concrete wall at noon will enter the interior living space around 8 p.m.

Definition of SHGC: Solar Heat Gain Component

Reader Question: how can windows of the different sizes have the same SHGC?

First off, I love your home page & have added it to my desktop. I read that your organization may provide pro-bono to the elderly & veterans, thank you for that possibility.

Not to push the issue but I would GREATLY appreciate your assistance (currently a 3 campaign veteran, also somewhat elderly, eligible for AARP next year, LOL). I would like to know if it’s possible, seems so, that windows of different sizes could all have the same SHGC? I am preparing to deny a building contractor on the basis of the area weighted average for fenestration?

Any assistance/information provided would greatly edify me and shared with other plan examiners. Thank you once more for your consideration.

- [Anon, email on file] - a building official in San Antonio TX., 1 Sept 2015Reply: SHGC - solar heat gain coefficient for windows:

Bottom line:

SHGC is a number most widely used just to describe a ratio - or quoting Anderson, "the fraction of solar radiation admitted through the glass of a skylight, window or door both directly transmitted and absorbed and subsequently released inward.

The lower the SHGC value, the less heat is transmitted through the product.

As used in the specs your builder submitted we know only the rating of the windows' glazing not the actual total solar gain of the building thanks to its fenestration. That's because no one has calculated glass area, orientation, actual sun exposure and other variables that all make for an engineering question.

If your local codes just specify the desired SHGC rating they're not specifying an actual absolute solar gain rate for the individual building.

Details

Based on my reading (I suspect you know more about this than I do but I appreciate the question and welcome the disussion):

The total heat gain through two windows of identical size, identical glazing, and exposed to the identical amount of sunlight, will be the same if we ignore other factors that might change individual window performance such as installation quality and air infiltration.

A window that is X% smaller in glass area but othewise of the same glazing and orientation and sun exposure, surely would have X% smaller total solar gain and a smaller SHGC for that window.

I suspect the "trick" the contractor is using or the mistake she or he made was to refer not to the whole window SHGC but rather to the SHGC of the glass or glazing of the windows. That's because the same term, at least in the U.S., is used also to refer to the solar gain rating of the glass itself.

I looked for SHGC data for some popular window brands that I've installed and inspected: Anderson & Marvin. Both manufacturers use data provided by the NFRC.

Marvin: gives SHGC data but it's about 50 clicks to get there.

at https://www.marvin.com/support/energy-data

you can select a specific window, choose many details, and then get the SHGC.A Marvin wood frame, casement window with grilles between glass and argon filled (with a few other parameters too) lists an SHGC of 0.42. Note that this number was given without any specification of the actual window dimensions. Therefore it has to be giving me a value for the glazing or window structure before considering area.

Anderson's NFRC Ratings for 400 Series Windows & Patio Doors 5 MB

lists SHGC targets from >= 0.25 to 0.42 depending on the energy zone and has detailed tables listing U factors, SHGC, VT and other paramaeters for windows by glass type - again independent of window size.

Factors Needed to Convert SHGC Ratings to Actual Building Solar Heat Gain

Since the SHGC is a transmittance factor, I pose (as I'm not expert on this) that to calculate the solar gain data for a specific building (which we will call total solar heat gain factor for the building) we'd need additional data including at least

- Factor for solar shading that must be combined with SHGC.

- Factors for areas of a building that are or are not actually shaded, or perhaps factors for different sides of the building that have different orientation to the direction of sunlight (or compass orientation)

- The angle of the glazing with respect to the sky

- Total square inches of glass of each SHGC rating on each side of the building

- Climate zone of the building - where it is located on the earth, e.g. distance from the equator

- Window model specifics besides glass type including use of grilles, divided lights, etc.

- Actual air leakage at each window or possibly a total window air leakage measurement for the building

To calculate actual solar heat gain and for more about SHGC see SOLAR GAIN CALCULATION.

Quoting Wikipedia on SHGC

Solar Heat Gain Coefficient (SHGC) is used in the United States and most commonly refers to the solar energy transmittance of a window or door as a whole, factoring in the glass, frame material (wood, aluminum, etc.), sash (if present), divided lite bars (if present) and screens (if present).

SHGC may also refer to the solar energy transmittance of the glass alone (sometimes more specifically termed center-of-glass SHGC), in which case it is analogous to g-value.

... g-values and SHGC values ranges from 0 to 1, a lower value representing less solar gain. Shading coefficient values are calculated using the sum of the primary solar transmittance (T-value) and the secondary transmittance.

Primary transmittance is the fraction of solar radiation that directly enters a building through a window compared to the total solar insolation, the amount of radiation that the window receives.

The secondary transmittance is the fraction of inwardly flowing solar energy absorbed in the window (or shading device) again compared to the total solar insolation.

...

For triple glazing, consider a whole-window SHGC in the range 0.33 - 0.47; for double glazing consider a SHGC in the range 0.42 - 0.55 (the higher the better). - retrieved 2 Sep 15

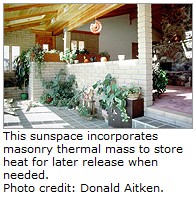

How a Sunspace Provides Isolated Solar Gain

The most common isolated-gain passive solar home design is a sunspace. A sunspace—also known as a solar room or solarium—can be built as part of a new home or as an addition to an existing one.

The simplest and most reliable sunspace design is to install vertical windows with no overhead glazing. Sunspaces may experience high heat gain and high heat loss through their abundance of glazing.

The temperature variations caused by the heat losses and gains can be moderated by thermal mass and low-emissivity windows. For more information, see sunspace orientation and glazing angles.

The thermal masses that can be used include a masonry floor, a masonry wall bordering the house, or water containers. The distribution of heat to the house can be accomplished through ceiling and floor level vents, windows, doors, or fans.

Most homeowners and builders also separate the sunspace from the home with doors and/or windows so that home comfort isn't overly affected by the sunspace's temperature variations. For more information, see [at U.S.DOE or below] sunspace heat distribution and control.

Sunspaces may often be called and look a lot like "greenhouses." However, a greenhouse is designed to grow plants while a sunspace is designed to provide heat and aesthetics to a home, as our photographs of a Poughkeepsie New York home illustrate [left & below].

Many elements of a greenhouse design that are optimized for growing plants, such as overhead and sloped glazing, are counterproductive to an efficient sunspace.

Moisture-related mold and mildew, insects, and dust inherent to gardening in a greenhouse are not especially compatible with a comfortable and healthy living space.

and see INDOOR AIR QUALITY IMPROVEMENT GUIDE -DF]

Also, it is difficult to shade sloped glass to avoid overheating, while vertical glass can be shaded by a properly sized overhang.

Photo-Example of A Sunspace for a Cold Climate

[Our photos (above and at left) show a sunspace constructed by the author D Friedman in Poughkeepsie, New York.

This addition includes continuous operable awning-type windows around three sides of the structure (North, East, South). In order to maximize solar gain during winter months in this northern climate (Mid Hudson Valley, New York).

The roof was designed with only a minimal overhang. The West side of the addition is its point of attachment to the original building.

This sunspace was well insulated in its roof and lower walls below the windows, and the space can be opened to share air and heat with the rest of the building (lifting out a sliding glass door).

As this sunspace was built by modifying an existing screened porch, we did not construct a thermal-mass floor: the space was constructed over a crawl area, but the floor has been insulated below using two-inch solid-foam board insulation placed between the floor joists, immediately below the wood flooring.

Even with heat turned off into this room, it reaches the high 50's, low 60's in cold winter months. Roof overhang design for passive solar homes is discussed below. -DF]

List of Passive Solar Design Key Reference Books including Online Texts

The first three passive solar design handbook links below are to free, online documents.

- PASSIVE SOLAR DESIGN HANDBOOK VOLUME I [PDF], the Passive Solar Handbook Introduction to Passive Solar Concepts, in a version used by the U.S. Air Force

- PASSIVE SOLAR DESIGN HANDBOOK VOLUME II [PDF], the Passive Solar Handbook Comprehensive Planning Guide, in a version used by the U.S. Air Force - online version available at this link and from the USAF also at wbdg.org/ccb/AF/AFH/pshbk_v2.pdf [This is a large PDF file that can take a while to load]

- PASSIVE SOLAR HANDBOOK VOLUME III [PDF], the Passive Solar Handbook Programming Guide, in a version used by the U.S. Air Force - online version available at this link and from the USAF also at wbdg.org/ccb/AF/AFH/pshbk_v3.pdf

- The Passive Solar Design and Construction Handbook, Steven Winter Associates (Author), Michael J. Crosbie (Editor), Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-047118382 or 0471183083 the The Passive Solar Design and Construction Handbook, Steven Winter Associates (Author), Michael J. Crosbie (Editor), Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-047118382 or 0471183083

- "PASSIVE SOLAR HOME DESIGN [PDF] ", U.S. Department of Energy, describes using a home's windows, walls, a nd floors to collect and store solar energy for winter heating and also rejecting solar heat in warm weather.

Here we include solar energy, solar heating, solar hot water, and related building energy efficiency improvement articles reprinted/adapted/excerpted with permission from Solar Age Magazine - editor Steven Bliss.

...

Continue reading at PASSIVE SOLAR DESIGN METHOD or select a topic from the closely-related articles below, or see the complete ARTICLE INDEX.

Or see these

Recommended Articles

- PASSIVE SOLAR DESIGN HANDBOOK - PDF

- PASSIVE SOLAR DESIGN KEY ELEMENTS

- PASSIVE SOLAR DESIGN METHOD

- PASSIVE SOLAR ENERGY MONITORING

- PASSIVE SOLAR FLOOR TILES, PHASE CHANGE

- PASSIVE SOLAR HEAT PERFORMANCE

- PASSIVE SOLAR HOME, LOW COST

- PASSIVE SOLAR PERFORMANCE PROBE

- PASSIVE SOLAR Roof & Window OVERHANGS

- SOLAR ENERGY SYSTEMS - home

- SOLAR GAIN CALCULATION

Suggested citation for this web page

SOLAR GAIN TYPES, DEFINITIONS at InspectApedia.com - online encyclopedia of building & environmental inspection, testing, diagnosis, repair, & problem prevention advice.

Or see this

INDEX to RELATED ARTICLES: ARTICLE INDEX to SOLAR ENERGY

Or use the SEARCH BOX found below to Ask a Question or Search InspectApedia

Ask a Question or Search InspectApedia

Solar design handbook questions and answers about passive soalr gain.

Try the search box just below, or if you prefer, post a question or comment in the Comments box below and we will respond promptly.

Search the InspectApedia website

Note: appearance of your Comment below may be delayed: if your comment contains an image, photograph, web link, or text that looks to the software as if it might be a web link, your posting will appear after it has been approved by a moderator. Apologies for the delay.

Only one image can be added per comment but you can post as many comments, and therefore images, as you like.

You will not receive a notification when a response to your question has been posted.

Please bookmark this page to make it easy for you to check back for our response.

IF above you see "Comment Form is loading comments..." then COMMENT BOX - countable.ca / bawkbox.com IS NOT WORKING.

In any case you are welcome to send an email directly to us at InspectApedia.com at editor@inspectApedia.com

We'll reply to you directly. Please help us help you by noting, in your email, the URL of the InspectApedia page where you wanted to comment.

Citations & References

In addition to any citations in the article above, a full list is available on request.

- [1] Passive Solar Home Design - U.S. DOE Suggestions energysavers.gov/your_home/designing_remodeling/index.cfm/mytopic=10250

- [2] How a Passive Solar Home Works - U.S. DOE original source: energysavers.gov/your_home/designing_remodeling/index.cfm/mytopic=10260

- [3] Direct Solar Gain - U.S. DOE - original source: energysavers.gov/your_home/designing_remodeling/index.cfm/mytopic=10290

- [4] Indirect Solar Gain - U.S. DOE - original source: energysavers.gov/your_home/designing_remodeling/index.cfm/mytopic=10300

- [5] Isolated Solar Gain - U.S. DOE - original source: http://www.energysavers.gov/your_home/designing_remodeling/index.cfm/mytopic=10310

- [6] Passive Solar Window Design - U.S. DOE energysavers.gov/your_home/windows_doors_skylights/index.cfm/mytopic=13360

- PASSIVE SOLAR DESIGN HANDBOOK VOLUME I [PDF], the Passive Solar Handbook Introduction to Passive Solar Concepts, in a version used by the U.S. Air Force

- PASSIVE SOLAR DESIGN HANDBOOK VOLUME II [PDF], the Passive Solar Handbook Comprehensive Planning Guide, in a version used by the U.S. Air Force - online version available at this link and from the USAF also at wbdg.org/ccb/AF/AFH/pshbk_v2.pdf [This is a large PDF file that can take a while to load]

- PASSIVE SOLAR HANDBOOK VOLUME III [PDF], the Passive Solar Handbook Programming Guide, in a version used by the U.S. Air Force - online version available at this link and from the USAF also at wbdg.org/ccb/AF/AFH/pshbk_v3.pdf

- The Passive Solar Design and Construction Handbook, Steven Winter Associates (Author), Michael J. Crosbie (Editor), Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-047118382 or 0471183083

- "PASSIVE SOLAR HOME DESIGN [PDF] ", U.S. Department of Energy, describes using a home's windows, walls, and floors to collect and store solar energy for winter heating and also rejecting solar heat in warm weather.

- SOLAR WATER HEATERS [PDF] , U.S. Department of Energy article on solar domestic water heaters to generate domestic hot water in buildings, explains how solar water heaters work. Solar heat for swimming pools is also discussed.

- ABSORPTION HEAT PUMPS & COOLERS [PDF] , U.S. DOE

- SOLAR AIR HEATING [PDF] U.S. DOE also referred to as "Ventilation Preheating" in which solar systems use air for absorbing and transferring solar energy or heat to a building

- SOLAR LIQUID HEATING [PDF] U.S. DOE, systems using liquid (typically water) in flat plate solar collectors to collect solar energy in the form of heat for transfer into a building for space heating or hot water heating. The term "solar liquid" is used for accuracy, rather than "solar water" because the water may contain an antifreeze or other chemicals.

- In addition to citations & references found in this article, see the research citations given at the end of the related articles found at our suggested

CONTINUE READING or RECOMMENDED ARTICLES.

- Carson, Dunlop & Associates Ltd., 120 Carlton Street Suite 407, Toronto ON M5A 4K2. Tel: (416) 964-9415 1-800-268-7070 Email: info@carsondunlop.com. Alan Carson is a past president of ASHI, the American Society of Home Inspectors.

Thanks to Alan Carson and Bob Dunlop, for permission for InspectAPedia to use text excerpts from The HOME REFERENCE BOOK - the Encyclopedia of Homes and to use illustrations from The ILLUSTRATED HOME .

Carson Dunlop Associates provides extensive home inspection education and report writing material. In gratitude we provide links to tsome Carson Dunlop Associates products and services.