Thatch Roof Types, Inspection, Maintenance Guide

Thatch Roof Types, Inspection, Maintenance Guide

- POST a QUESTION or COMMENT about thatch roofing on buildings

Thatched roofing guide:

This article describes types of thatch roofing used on buildings, with a brief history of thatch and a focus on contemporary use of this roofing method. Thatch roofing is not only a very old and well established (though high labor) roof covering method used in many parts of the world, it is also used on a wider variety of types of buildings than you might expect.

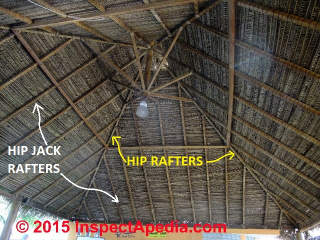

Our page top photo illustrates a palapa roof beneath which the author both hosted visitors and slept in Mexico in 1976. In the article below we illustrate types of thatch roofing from around the world.

Thatch roofing is still in active use in many countries making use of local grasses, hemp, straw, palms, or other materials as well as using synthetic thatch made from a variety of materials including recycled waste plastic materials. This website provides un-biased articles about many common roofing materials, installations, inspection, defects, roofing repairs, and products.

InspectAPedia tolerates no conflicts of interest. We have no relationship with advertisers, products, or services discussed at this website.

- Daniel Friedman, Publisher/Editor/Author - See WHO ARE WE?

Thatch Roofing Installation, Properties, Fire Safety, Maintenance, Research

[Click to enlarge any image]

At above is a thatched roof home in Wolvercote, Oxford, England, U.K. The Wolvercote thatch roof is covered with netting, most likely to make the thatch roof less inviting as living space for birds or other pests.

At above right is the a palm leaf thatched roof used on the shelter mounted on Thor Heyerdahl's 1947 Kon Tiki Raft. (The Kon Tiki and its shelter are preserved at the Kon Tiki museum in Oslo, Norway.) At below left is a thatch roofed windmill in Holland showing thatch used on a very steep sloped roof surface.

Article Contents:

Traditional thatch roofing was constructed of straw, combed wheat, longstraw, broom, sod, and water reed (Phragmites australis). But other plant materials have been used depending on what was readily available in various parts of the world, including palm leaves and plant fragments.

Thatched roofs were typically installed on steep sloped roof structures in order to shed water rapidly (rather than absorbing it).

Life Expectancy of Thatch Roofs

Our photos (below) show the exterior and also the interior structure a traditional Mexican thatch roof used at the visitors' center of el Charco, an environmental park in San Miguel de Allende, Guanajuato, Mexico (2004). The interior photo (below right) shows how the thatch roof skylight window was constructed. A close up of this window seen from outside is provided below in this article.

Water reed thatched roofing can last up to 50 years. Combed wheat reed typically has a life expectancy of 25 - 35 years, and long straw 15 - 25 years. For all of these traditional thatch roof types, re-ridging is needed about every 10 - 15 years.

The life of a thatch roof varies considerably depending on the roof slope (shallower or lower pitch thatched roofs are more likely to leak, absorb water, and have a short life), and on the geographic area where the roofed building is located. The typical slope of a thatched roof structure is 50 degrees. But as we explain next, the slope of the roof structure is not the same as the slope of the thatch itself.

The life of a thatch roof is also significantly affected by the thickness of the thatch, since a thicker thatch results in a less-steep angle of the individual reeds or straws. A less steep reed or straw angle results in a shorter roof life. A 9-15" thickness is recommended for a water reed thatch roof and a 9-12" thatch is recommended for wheat reed and longstraw thatches.

Insulating Value of Thatched Roofs

Insulating Value of Thatched Roofs is generally about R-11 for a typical 9-12" thick thatch. The Dorset Building Control Technical Committee (cited below) notes the following U values for Reed and Straw thatch:

In order to achieve a ‘U’ value of 0.2w/m2K for thatched roofs, the following was taken from CIBSE Guide A3:

Reed = thermal conductivity 0.09 and a resistivity of 11.1

Straw = thermal conductivity 0.07 and a resistivity of 14.3

This gives a ‘U’ value of 0.2/m2K for 450mm of reed and 350mm of straw. On this basis ceilings may require additional insulation. - op cit.

Example of Traditional Method for Preparing Palm Thatch

Above and below we illustrate palm thatch roofing in current use in La Manzanilla on the Pacific coast of Mexico. Local owners told me that the life of a palm thatch roof may be as short as five years. Individual palm leaves used in thatching at Barra de Potosi cost about 5 pesos which may sound inexpensive, but thousands of palm leaves may be required for a larger roof, and that is of course a cost before labor is added.

The preparation of roof thatching material varies considerably around the world depending on the plant used for thatching.

Our example below quotes drawings and text from US Patent US7900415 B2 by original inventors Carlos Armando and Azcué García whose patent application for a procedure to produce (synthetic) palm roof tiles for rustic roofs includes twenty illustrations of the traditional thatch preparation methods described just below. The patent citation is given in detail below.

Quoting from the Armando Garcia patent:

[Click to enlarge any image]

Comments from the cited patent explain the use of the palm to produce thatch for a Mexican type palapa.

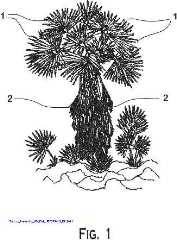

FIGS. 1 to 6 correspond to the plant called Brahea dulcis, which has simple leaves like a fan, green in the fascicle and pale in the back, divided into 40 to 60 segments that measure 40 to 50 cm in length; the leaves 1 are concentrated in the top end of the stem and going down there are some fallen leaves 1.

The leaves have marginal teeth 2 2.4 cm in length; the palm leaf presents hanging inflorescence in a raceme shape, which are 1 to 3 m in length.

Brahea dulcis is the most abundant species of the Arecaceae family and can be found in many calcareous soils located from 900 to 1900 m above sea level.

Popular names include “hat palm”, “sweet palm”, “fan palm”, “common palm”, “apache palm”, “pochitla palm”, and “soyal” or “soyate”.

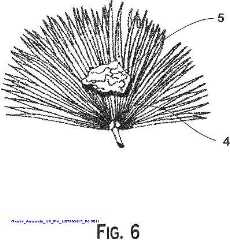

When the leaves 4 are ripe they have a fan shape and after they are cut they shrink.

To avoid shrinking a stone or other heavy object 5 is put on them.

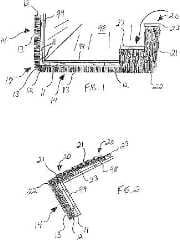

FIG. 1 is a conventional inferior view of a palm plant B. dulcis with some inferior leaves fallen.

FIG. 2 is a conventional superior view of the plant shown in FIG. 1.

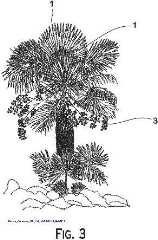

FIG. 3 is a view of plant B. dulcis showing hanging inflorescence in a raceme shape.

FIG. 4 shows a ripe palm leaf in a fan shape.

FIG. 5 shows a palm leaf that contracts after being cut.

FIG. 6 shows a palm leaf that was cut and has a heavy object on it (e.g., a stone) to avoid shrinking of the leaves.

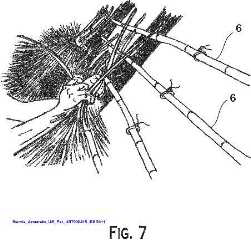

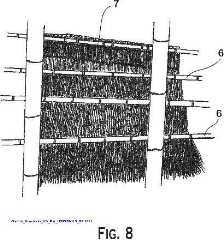

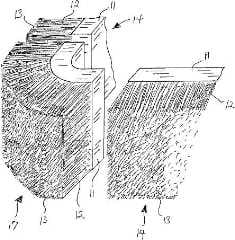

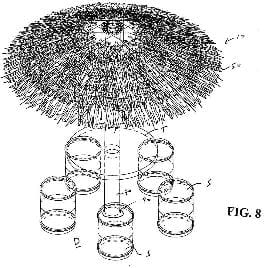

FIG. 7 shows the traditional fastening or fixing of the pressed leaves onto crosspieces. FIG. 7 shows how roofs are traditionally constructed using pressed palm leaves, where they are individually tied, knitted over the crossbars 6 overlapping its collocation 7. As demonstrated in FIG. 8, by contrast, using self-supporting palm tiles 7 according to the present disclosure, being previously knitted, are hooked onto the crossbars 6 staying firmly fastened.

The procedure to manufacture palm tiles is as follows:

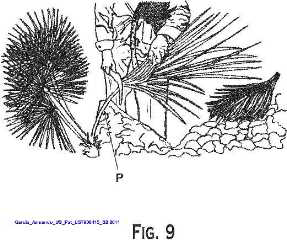

a) Collect the palm leaves manually directly from the tree holding the leaf with one hand and cutting and separating the petiole P with the other (see FIG. 9).

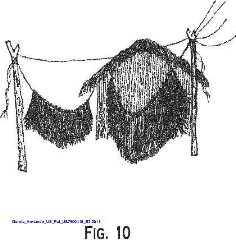

b) Dry the leaves by exposing them directly to the sun rays (see FIG. 10) or by a mechanical dehydrating process using a dehydrator (not shown).

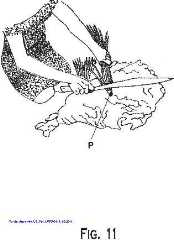

c) Cut the excess of petiole manually or mechanically down to the base (see FIG. 11).

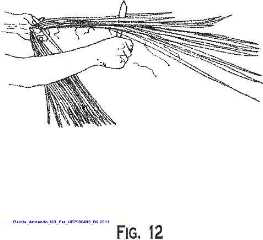

d) Cut or tear the leave lengthwise into two parts (see FIG. 12) using a punching object or a mechanical instrument.

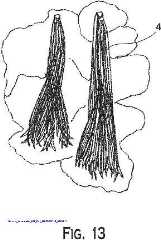

e) Select the leaves by size (see FIG. 13) so they have a uniformed presentation.

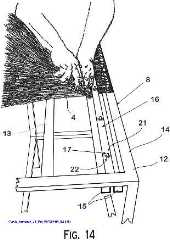

cf) Place and arrange the leaves two by two (see FIG. 14) in a mold 8 which can be of any size but designed to avoid deformations of the palm tile when it is sewn.

g) Sew, glue, staple, fasten or tie up the leaves using a strap 16 where the fan begins taking advantage of the natural union of the lamina and the petiole.

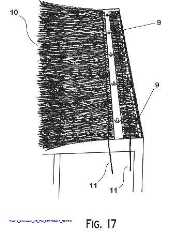

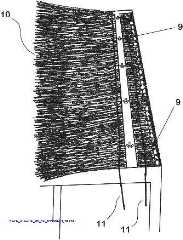

h) At this stage of the process (or later) the hooks are fixed 9 (when used) onto the finished tile 10 by setting the threads 11 for sewing perpendicularly.

FIG. 8 illustrates the collocation and fastening of a palm tile onto crosspieces.

FIG. 9 shows how leaves are collected.

FIG. 10 illustrates the drying of the leaves outdoors with the help of sun rays.

FIG. 11 shows the cutting of the petiole.

FIG. 12 shows the lengthwise cut of the palm leaf.

FIG. 13 shows the hanging of the leaves to select sizes.

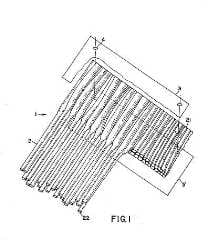

FIG. 14 illustrates the collocation and arrangement of the selected leaves pair by pair in a mold. FIG. 14 shows a mold 8, which in this particular embodiment is a rectangular table 12 with a crossbar 13 intermediate and an extreme crossbar formed by a crosspiece 14, two lower 15 crossbars and a strap 16 with orifices 22 and screws 21 extending therethrough as shown to screw and tighten it with butterfly nuts 17 to press the leaves between strap 16 and lower cross-bars 15.

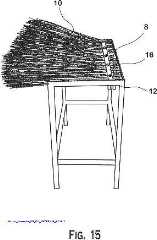

FIG. 15 shows the mold with the leaves set and fixed and screwed with a crossbar to prevent movement. FIG. 15 shows the mold 8 as a rectangular table 12 with the leaves set and fixed and screwed with a crossbar to prevent movement.

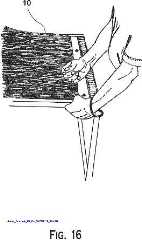

FIG. 16 shows the sewing of the tile, which is in the mold.

FIG. 17 shows the hooks or clips, whichever are chosen. FIG. 17 shows the hooks or clips 9, fixed onto the finished tile 10 by threads 11.

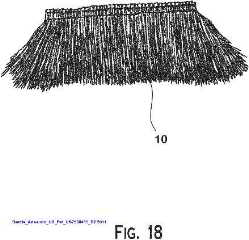

FIG. 18 shows a finished tile. FIG. 18 shows a finished self-supporting palm tile 10 removed from mold 8 after forming.

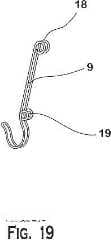

FIG. 19 shows a hook shaped attachment to fasten to the crossbars. FIG. 19 shows a hook 9, that has two loops in its body 18 and 19 that are used to hold to the threads for sewing the tile and the hook is held to a crosspiece or “strap” to the structure of hut or palapa fixing the tile.

These hooks 9 can be of diverse materials, the most common ones are plastic and wire, their shape and size depend on the crosspiece but the purpose is the same, to hang and to set the tile to form the palm roof.

The leaves and/or the tiles, whether in process or finished, can have a chemical or natural treatment to preserve the color, avoid infestation by plagues or/and delaying or inhibiting fire and/or different finishing measures or special accessories that facilitate the fixing or placement in the structures of huts or palapas that hold them.

The disclosure of every patent, patent application, and publication cited herein is hereby incorporated herein by reference in its entirety.

While this invention has been disclosed with reference to specific embodiments, it is apparent that other embodiments and variations of this invention can be devised by others skilled in the art without departing from the true spirit and scope of the invention. The appended claims include all such embodiments and equivalent variations.

- Azcué, Armando Carlos García. "Procedure to manufacture palm roof tiles for rustic roofs and the obtained product." U.S. Patent 7,900,415, issued March 8, 2011.

The palm thatched roof above and below is on a structrure forming part of a hotel restaurant on the Pacific coast of Mexico.

As I show below, some of these palm-thatched roofs on the Pacific coast are covered outside by a wire mesh net, perhaps to reduce wind damage.

Simulated or Synthetic Thatch Roofing

Synthetic thatch roofing material including plastic products made from plastic waste has applications not only as a replacement for natural materials on building roofs but interestingly in other applications such as use of synthetic thatch for temporary shelters (Golden 2005) and even for producing a synthetic ski slope (Wehr 1963).

Illustrated above are designs for a thatch eave member explained by Huber in their patent as follows: [Excerpting]

... the invention relates to such roofing members known as thatching, which are used to create what are termed thatch roofs, wherein the term thatch is taken to include both natural and synthetic materials. Even more particularly, the invention relates to discrete thatch members in the forms of shingles or rolls that are applied in multiples to the roof to provide the appearance of a natural thatch roof.

Thatch roofing has been used to create shelter from the elements of sun and rain for thousands of years.

The type of thatch roofing often varies by region, with roofing in the Caribbean and South Pacific typically formed of grasses or palm fronds and presenting a generally loose or random appearance, while thatch roofing in Europe is typically formed of straw and reeds and presenting a more controlled or dressed look.

Thatch may be made from natural elements such as straw, grasses, reeds, palm leaves or the like, and in modern times is also made from artificial or synthetic elements, typically composed of plastic, which are formed to present the appearance of natural thatch material.

The modern thatch roofing members which incorporate artificial material are more durable, typically easier to construct and apply, and are more resistant to mold, mildew and other forms of degradation or weathering. The overall appearance of the roof is more easily controlled.

Because the aesthetics of a thatched roof are unique, thatch roofing is gaining in popularity. Natural thatch is typically highly combustible, and therefore cannot pass building codes in many jurisdictions. Natural thatch is also very susceptible to rotting and degradation due to high humidity and moisture, and presents natural nesting material for insects, vermin and birds.

Furthermore, natural thatching requires skilled artisans for the construction of the individual thatch members and for the installation of the roof—a skill which is rapidly disappearing.

The development of synthetic or artificial thatching has lessened or obviated some of the these problems. The artificial thatching is typically produced in the form of rolls or shingles which are properly disposed on the roof to form a waterproof surface with a pleasing exterior. An example of artificial thatch elements is shown in my U.S. Pat. No. 6,226,949, the disclosure of which is incorporated herein by reference.

Since natural thatching consists of individual reeds, palm fronds, etc., multiple layers of such materials are necessary to form a water impermeable covering.

Because of this necessity, the exposed ends or faces of the thatch elements along the eaves of the roof are relatively thick. In modern construction where artificial thatch elements are utilized, an underlayment of water impermeable sheet material allows the covering members to be produced as thin elements, thereby lowering manufacturing costs and easing application to form the roof.

However, the use of thin shingles or rolls of synthetic thatch presents an undesirable appearance along the eaves of the building, since the entire thickness of the lowermost thatch shingle or roll is exposed to the observer. Since natural thatch roofs are by requirement relatively thick, this exposed thin edge indicates that the roof is not a true thatched roof, detracting from its appeal.- Barry Ray, and Abram Huber. "Thatch eave member." U.S. Patent 7,117,652, issued October 10, 2006.

Synthetic Thatch Roofing Patents of interest:

[Click to enlarge any image]

Shown at above left, Golden's synthetic thatch tiki shelter, and at above right, Friedhelm Houpt's synthetic thatch plastic stalk roof segment patented roof design cited below.

- Azcué, Armando Carlos García. "Procedure to manufacture palm roof tiles for rustic roofs and the obtained product." U.S. Patent 7,900,415, issued March 8, 2011.

Abstract: Provided herein are compositions for palm tile, which consists of an assembly of leaves of the palm tree Brahea dulcis, previously torn, placed in a uniformly and symmetrically way and lengthwise sown, stapled or held to the part where the petiole meets the lamina to form a tile, board, panel or Hawaiian skirt.

Also provided herein are methods to manufacture the tiles and elements for its elaboration and placement on crosspieces of a structure.

Background:

The disclosure relates generally to the field of construction materials. It is a new product called palm tile that can be used to construct roofs or to cover huts or “palapas”. This is a new procedure to manufacture palm tiles.

In several places and communities in the world, natural leaves, stems, branches, grass or hay are still being used for constructing traditional roofs of houses or shelters.

In Mexico and other countries, stretched or pressed leaves from palm trees are tied up or fastened onto wooden or other material structures to construct roofs or covers for huts or “palapas”.

In the traditional system to construct rustic roofs, the framework is assembled first; stretched or pressed palm leaves are then fastened or affixed thereto. However, fastening or fixing these leaves to the structure is a hardworking and slow job, which is both expensive and inconvenient because it takes a lot of time for workers to do it.

To construct roofs of huts and “palapas” using natural leaves and branches among other materials, various types of frameworks are used, whether conic or sloping (e.g., single pitch or double pitch roof) or eccentric. In all cases, material is laid and tied to use in overlaid portions, overlapping its position depending on the vegetal material used, with the previously mentioned inconveniences. ...

Provided herein is information for the construction of palm tiles or thatched roofs, rustic roofs for huts or “palapas”, which surpasses the inconveniences of the traditional technique.

Collocation time is also reduced with highly satisfactory results. Also disclosed are methods to manufacture palm tiles, some accessories to fix them, and the manner to fix it onto a framework....

The palm tile disclosed herein is an ensemble from the Brahea dulcis (B. dulcis) palm leaves placed uniformly and symmetrically which previously were cut lengthwise or in narrow strips, sewed, stapled or fastened to the part where the petiole connects its lamina as a tile, panel, leaf or Hawaiian skirt and used to construct rustic roofing or to decorate. The palm leaves of these tiles can be sewed or fastened with different materials. The tiles can have different sizes, lengthwise and widthwise according to the actual size of the leaves. - Butler, Delicia M. "Simulated thatched roofing." U.S. Patent 4,739,603, issued April 26, 1988. Abstract:

There is disclosed a simulated thatched roofing which closely approximates the appearance and durability of thatched roofs.

The roof structure includes a supporting roof structure formed of a roof frame and a base underlayment and a natural or synthetic fiber outer covering laid thereover which is formed of a base sheet, which can be woven or unwoven fabric, with or without a laminated layer of a synthetic resin, or can be a layer of a natural or synthetic resin in which a plurality of discontinuous loops of a synthetic or natural, raw bast or leaf fiber are embedded.

The loops are cut to the ends of the fibers as tufts which are closely spaced across the entire surface of the roof covering, and which simulate the cut ends of reeds used in traditional roof thatching. - Golden, William. "Tiki shelters and kits." U.S. Patent Application 10/829,681, filed April 22, 2004. Abstract excerpts:

Novel artificial tiki shelters and tiki shelter roofs are disclosed and claimed herein. ... The present invention is directed to novel artificial shelters, in particular artificial tiki shelters that may be marketed in kits for easy assembly by the consumer.

The inventive tiki shelter, unlike conventional tiki huts (also known as “chickee huts”), which are made substantially from natural materials (e.g. natural thatch and wood), is very sturdy upon assembly, able to withstand winds of up to 150 miles per hour. - Hrušková, Lenka, and Jindřiška Šulistová. "Stavitelská angličtina." (2012) [PDF]

- Houpt, Friedhelm. "Roof covering element comprising plastic stalks." U.S. Patent 5,333,431, issued August 2, 1994.

- Huber, Barry Ray, and Abram Huber. "Thatch eave member." U.S. Patent 7,117,652, issued October 10, 2006. Abstract:

A thatch eave member formed of a plurality of individual thatch elements, either natural or synthetic, having a backing member retaining a plurality of individual thatch elements such that the free ends present a generally planar exposed face, wherein the backing member is adapted for attachment along the eave of a roof such that the exposed face matches the ends of a lowermost thatched roofing shingle or roll to give the illusion of a thicker roof, and the system comprising the combination of such eave members and roof members. - Kuroishi, Izumi. "Socio-cultural Sustainability In Traditional Architectural Techniques: Combining Traditional Thatched Roof Culture With Modern Daily Household Management Techniques." [PDF] - retrieved 10 June 2015, original source: http://www.irbnet.de/daten/iconda/CIB3959.pdf - Excerpt from Summary:

This paper aims to examine how the management of traditional technologies presents social frameworks of the sustainability of architecture, particularly, by putting more emphasis on the relationship between technology and people’s social and lifestyle circumstances. In Japan, the disappearing thatched house represents the organic and synthetic relationship between its form and the technique, and the social organization involved in its construction.

In the design and construction of a new thatched house, we experimented several methods of technology management: approaching the problems not from the physical conditions of the house but from the psychological and symbolic meaning of the house, and demonstrating a new and flexible understanding of the interior climate conditions, and tried to create a new way of making a thatched roof house. - Latif, Eshrar, D. Chitral Wijeyesekera, Darryl Newport, and Simon Tucker. "Potential for research on hemp insulation in the UK construction sector." (2010). Abstract [excerpt]:

Hemp based thermal insulation has the potential to reduce CO2 emissions from buildings and to be 'carbon-negative' in its production and manufacture.

Hemp has been in use to produce biobased natural fibre insulation in the UK in recent years. With further development in hemp agronomy, production process and selection of raw materials in the production, hemp-based insulation materials are likely to become environmentally and functionally superior products to other insulation materials developed from petrochemical and mineral based sources. - Saiia, David. "Apparatus and method for producing a thatch roofing material for building construction." U.S. Patent 8,425,390, issued April 23, 2013. - This patent describes not thatch roofing itself but a machine for producing synthetic thatch from plastic waste material. Abstract:

An apparatus and method for producing a thatch roofing material for building construction, the apparatus includes a pair of stanchions, a supporting frame, at least one holding member for holding the container, a first shaft extending substantially perpendicular to each stanchion of the pair of stanchions, and a blade coupled to the first shaft for cutting the container. - Valentine, David Michael. "Synthetic thatch members for use as roofing material products and methods of making and using the same." U.S. Patent 8,984,836, issued March 24, 2015. Abstract:

A synthetic thatch member for use as a roofing material product, along with associated methods for manufacturing and installing the same are provided.

The synthetic thatch member comprises: a plurality of frond members defining a first three-dimensional surface of the thatch member and a second three-dimensional surface of the thatch member, the first and second surfaces comprising opposing sides of the plurality of frond members; a fused portion comprising a first portion of each of the plurality of frond members, wh

erein each of the first portions is connected relative to one another, such that the fused portion defines a substantially impermeable surface; and a serrated portion comprising a second portion of each of the plurality of frond members, each of the second portions being separated relative to one another, such that a plurality of gaps are defined between each of the plurality of frond members. - Wehr, Henry W., and Norman J. Guziak. "Synthetic ski slope." U.S. Patent 3,091,998, issued June 4, 1963. Abstract [excerpt]":

This invention relates to a new synthetic sheet adaptable to provide the surface for a ski or toboggan slope and a ski or toboggan slope prepared therefrom. More particularly, the present invention relates to a ski or toboggan slope surface, a top coat of hard generally spherical particles bonded together.

Thatched Roof Fire Safety

In the U.K. the Dorset Building Committee (cited below) notes that

Statistics show that 70% of fires in thatched homes are caused by solid fuel burning appliances. The installation of a woodburner or a multi fuel appliance requires great caution due to the extreme temperatures generated over prolonged periods. - op. cit.

But any spark or fire or heat source can start a fast-spreading thatch fire. Our friends who live in San Miguel de Allende, Guanajuato, Mexico enjoyed a thatch roofed palapa atop their home until the thatch roofing was set afire in 2010 by misguided fireworks set off by a neighbour.

The resulting fire ignited and burned rapidly and hot. Heat and fire not only destroyed the palapa but damaged ceramic tiles and glass block components of the structure below. Keep fires, fireworks, or other spark soruces at least 100 meters from your home or expect trouble.

Measures to improve the fire safety for thatched home

Watch out: depending on where you live, thatch roofing may not be permitted at all. Check with local building department and fire department officials.

- Immediate safety: in the event of a fire do not waste time investigating the fire or saving contents: evacuate everyone from the building and call the fire department from outside or from a the home of a neighbour.

- Chimneys: must be at least 1.8 meters above the rooftop and should include a spark arrestor. Keep chimneys clean and inspect them regularly (at cleaning) for creosote or other fire hazards.

- Construction or maintenance: do not use fire, spark, heating or blowtorch equipment where sparks or heat can cause a fire.

- Contents: inventoried, documented, insured, including being able to give rescue or salvage instructions to fire service experts

- Escape routes: kept fire escape routes clear, make sure they are properly located, rehearse their use with family members.

- Fire barriers below thatch roofs: Fire barriers may be installed (or required to be installed) below thatched roofs depending on where you live. In the U.K. fire barriers are made using a fire and water-resistant rigid board system and roof construction to meet the "Dorset Model" requirements for a 30-minute fire barrier (experts recommend a 60-minute fire barrier) or by using a 60-minute rated flexible fire barrier (not meeting the Dorset Model specifications).

- Fire-resistant spray treatments for thatch roofs: fire retardant sprays may be applied to thatch roofing both on the upper surface and to the underside of the thatch at the roof eaves. A fire retardant spray (note that the word "retardant" or slower does not mean "fireproof") increases the resistance of the thatch roof to fire from sparks and slows the spread rate of a thatch fire. In the northern hemisphere where they are used, fire retardant sprays are applied from early April to mid-October.

- Lighting: make sure that electrical wiring is properly installed, routed, secured, code-compliant, and that actual lighting fixtures (that can create enough heat to start a fire) are at least a meter away from any thatch.

- Smoke alarms: must be properly located, installed, maintained

The above was adapted and expanded from:

- HETAS, "Chimneys in Thatched Properties", [PDF], HETAS HETAS Limited

Orchard Business Centre

Stoke Orchard

Cheltenham

Gloucestershire

GL52 7RZ, Tel: 0845 634 5626, Email: info@hetas.co.uk

Web: www.hetas.co.uk (2009), - retrieved 10 June 2015, original source: http://specflue.com/resources/content/file/thatch/thatch-property-guide.pdf - Excerpt:

The National Society of Master Thatchers have already reported more than 79 thatch fires in the year to October 2009 with the majority being caused by chimney related problems when used with a multi fuel or wood burning stove. - NFU Mututal, "Protecting Your Thatched Home", NFU Mutual Insurance, - retrieved 10 June 2015, original source: https://www.nfumutual.co.uk/Global/PDFs%20-%20document%20library/Articles/protecting-your-thatched-home.pdf - Excerpt:

If you have a thatch roof, or you’re thinking of buying a thatched home, you might be worried about the risk of fire. In fact, your thatched home is no more likely to catch fire than a home with a conventional roof, as long as you understand what you’re dealing with. However, if your thatch roof does catch fire, it will be very difficult to control and the results could be devastating. Your home could be partially or totally destroyed. The good news is that managing the risks isn’t difficult. You just have to understand the dangers and take some simple steps to address them.

Treatments for Thatch Roofing: pesticides, fungicides, fire retardants

Thatched roofs present special concerns for both fire safety and insect or rodent infestation for which there are centuries of experience and modern solutions.

At above left is a large thatch roof at the Alberque Bosque Esquinas in Costa Rica. At above right and at below left are details from a thatch roof at el Charco del Inginero, San Miguel de Allende, Mexico.

at below right is the thatch roofed Anne Hathaway Cottage, actually a twelve-room farmhouse, where Anne Hathaway, wife of William Shakespeare, lived as a child on Newlands Farm in Shottery, Warwickshire England, near Stratford on Avon, England, U.K. (Daniel Friedman 1969). The earliest parts of this house were constructed before the 15th century.

Thatch Roof Treatment Research, Patents

Because product descriptions and patents are a helpful source of understanding of the issues faced by roofing products we include the following:

- Ansari, M. A., P. K. Mittal, R. K. Razdan, and C. P. Batra. "Residual efficacy of deltamethrin 2.5 WP (K-Othrine) sprayed on different types of surfaces against malaria vector Anopheles culicifacies." Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 28 (1997): 606-609.

- Dorset Technical Committee, "The Dorset Model, Thatched Buildings, New Properties and extensions", [PDF] Dorset Technical Committeee (2014), Email: dorsetmodel@thatchregister.com (to register Dorset Model properties), retrieved 10 June 2015, Original Source: https://www.dorsetforyou.com/media/153064/Dorset-Model-07-09/pdf/Dorset_Model_-_Accessible_version_-_ammended.pdf

- Greer, George J., Nancy A. Nix, Celia Cordón-Rosales, Beatriz Hernández, Charles M. MacVean, and Malcolm R. Powell. "Seroprevalence of Trypanosoma cruzi infection in three rural communities in Guatemala." Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública 6, no. 2 (1999): 110-116.

- Schofield, C. J. "Control Of Chagas' Disease Vectors", British medical bulletin 41, no. 2 (1985): 187-194.

- Society of Master Thatchers, Website: www.nsmtltd.co.uk

- Szabo, Zoltan. "Szalmatetok lángmentesitése." Múzeumi Mütárgyvédelem 1, no. 1 (1970): 187-191. [Research on fire retardant treatment for thatch roofing] Abstract:

The thatched roof is washed with 10% NaOH solution. In an hour the NaOH is washed off by water. The roof is sprayed with a solution of urea resin. After drying up the spraying continues with a solution containing 40 kg (NH4)2 HPO4, and 10 kg borax in 60 l water. It is followed by a repeated spraying with urea resin. The coating -- after the polymerization accelerated by the ray of sunlight -- doesn't change the appearance of the thatched roof; it is in soluble in water, and protects the roof from fire. - Taylor, P., J. Govere, and M. J. Crees. "A field trial of microencapsulated deltamethrin, a synthetic pyrethroid, for malaria control." Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 80, no. 4 (1986): 537-545. Abstract:

The synthetic pyrethroid deltamethrin was evaluated as a 15 mg/m2 residual application of a microencapsulated formulation for efficacy in malaria control in a 50 km2 area of north-eastern Zimbabwe. Results were compared with very large contiguous DDT sprayed (2 g/m2) and unsprayed areas.

A total of 3544 rooms were sprayed with deltamethrin. No significant side effects of the insecticide on spraymen were noted.

Mosquito captures were poor and inconclusive due to drought conditions, but the malaria vectors Anopheles arabiensis and An. gambiae were identified in the area, the former being 14 times more abundant than the latter in bait collections from an unsprayed area.

Monthly bioassays using laboratory-reared An. arabiensis showed a higher mortality of mosquitoes exposed on roofs for up to eight months after deltamethrin application and indicated a high mortality in deltamethrin sprayed houses than in DDT sprayed houses. Tests indicated that, after eight months, up to 50% of the deltamethrin remained on the roof and 25% on the wall.

Malaria transmission, evaluated by blood slide surveys at the beginning and end of the transmission season, was high in the unsprayed area, slightly less in the adjacent and incompletely isolated deltamethrin sprayed area, and absent or very low in the DDT sprayed area. The results were considered to be favourable for the use of deltamethrin in malaria control by means of residual house-spraying with the non-irritant dosage of 15 mg/m2, but require evaluation in larger trials. - Abass, F., L. H. Ismail, I. A. Wahab, and A. A. Elgadi. "A review of green roof: definition, history, evolution and functions." In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, vol. 713, no. 1, p. 012048. IOP Publishing, 2020.

- Billett, Michael, THE COMPLETE GUIDE TO LIVING WITH THATCH, [Book info] Michael Billett, Robert Hale (Publisher) 2003, ISBN-13: 978-0709071587. The author guides the reader through the development of thatching, the materials used, and the artistic work that creates the charm and beauty of a thatched roof.

There are extensive chapters giving a host of practical tips for those living in thatched houses, including the advantages and disadvantages, maintenance, fire precautions, costs, insurance, and more. A glossary reveals the many unusual terms used by the thatcher and there is a list of useful addresses for further advice.

The Complete Guide to Living with Thatch contains a wealth of practical information and advice for all those who live in or who are contemplating buying a thatched house. - Cattelino, Jessica R. "Thatched Roofs and Open Sides: The Architecture of Chickees and Their Changing Role in Seminole Society." (2016): 110-113.

- Fearne, Hacqueline, THATCH AND THATCHING, [Book info] Shire Library, 2008 ISBN-13: 978-0747805885.

The craft of the thatcher probably gives more pleasure to people than any other of our rural crafts. Thatching is a craft most people know nothing about and which is commonly thought to be dying out. In fact, thatchers in all three materials - water reed, long straw and combed wheat reed - now have an assured livelihood after two centuries of uncertainty.

This book outlines the history of thatching in Britain from its use as the commonest form of roofing to the present day and explains how the thatcher works with his traditional materials. - Hedderson, Terry AJ, John B. Letts, and Keith Payne. "Bryophyte diversity and community structure on thatched roofs of the Holnicote Estate, Somerset, UK." Journal of Bryology 25, no. 1 (2003): 49-60.

Abstract excerpts:

We investigated patterns of bryophyte species richness and community structure, and their relation to roof variables, on thatched roofs of the Holnicote Estate, South Somerset.

Thirty-two bryophyte species were recorded from 28 sampled roofs, including the globally rare and endangered thatch moss, Leptodontium gemmascens. ...

. Aspect has a slight and marginally significant effect on species diversity (accounting for an additional 6% of variation), with north-facing samples having slightly more species. Age also has a significant impact on total bryophyte cover after removal of outlying observations. TWINSPAN analysis of bryophyte cover data suggests the existence of at least five discrete communities.

Simple Discriminant Analyses indicate that these communities occupy different ecological subspaces as defined by the measured roof variables, with pitch, aspect and thatch age emerging as especially significant attributes. Contingency Analysis indicates that some communities are disfavoured by water reed as compared to wheat straw.

The findings are significant for understanding the structure of bryophyte communities, for evaluating the effect of bryophyte cover on thatch performance, and for conservation of thatch communities, especially those harbouring rare species. - Holden, Timothy G., THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF SCOTTISH THATCH, [Book info] Historic Scotland Technical Advice Notes, ISBN-13: 978-1900168496,

- Hunnisett, Jessica. "Understanding thatched buildings." Journal of Building Survey, Appraisal & Valuation 10, no. 1 (2021): 46-61.

- Katabami, Serusa. "THATCHED ROOFS AND OPEN-AIR MUSEUMS. A comparative study of Sweden and Japan." (2017).

Abstract:

The purpose of this thesis is to study how thatched roofs in Sweden and Japan have changed their characters over the time from a roof for residence to a museum object and how they are represented at open-air museums today while the craftsmanship is still alive and struggling for its survival. The methods for this research are literature studies, interviews, and observations.

Theories of Architecture mainly by Pallasmaa Juhani and UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage are applied to analyze the subjects from another aspect. This thesis highlights the tendency in open-air museums that lacks attention to thatched roof and its craftsmanship.

By rethinking the history of thatching and open-air museums and by introducing the concept of Architecture and Intangible Cultural Heritage this thesis concludes that thatched roofs and its craftsmanship should be narrated and shown to the visitors as it is a part of their collection. It would promote thatching and strengthen the role of open-air museums in the current society. - Sammells, Clare A. "7 Bargaining Under Thatch Roofs: Tourism and the Allure of Povertyin Highland Bolivia." Tourism and the power of otherness: Seductions of difference 34 (2014): 124.

- Lewis, Catherine, "Thatched Roofs - An Introduction," The Building Conservation Directory, 1995

- Thatched roof advisory information for the U.K. is at http://www.thatchingadvisoryservices.co.uk

- Walker, Bruce. "Getting your hands dirty: a reappraisal of Scottish building materials, construction and conservation techniques." Architectural Heritage 17, no. 1 (2006): 43-70.

Quick Comparison of Typical Roof Costs, Life Expectancy, Characteristics

at left is a plastic synthetic thatch roof produced by Chinese roofing supplier kebagm.com. OPINION: the chemistry of some synthetic roof materials, while avoiding historic health concerns such as those arising from mosquitoes or other insects may present health or environmental questions needing investigation.

at left is a plastic synthetic thatch roof produced by Chinese roofing supplier kebagm.com. OPINION: the chemistry of some synthetic roof materials, while avoiding historic health concerns such as those arising from mosquitoes or other insects may present health or environmental questions needing investigation.

Here is a quick comparison of common roofing materials. Our roofing inspection, diagnosis, repair and installation articles listed at left and below provide roof inspection, roof leak or problem diagnosis, roof installation, and roof repair information as well as details about the factors that affect the life of any roof. We include roof warranty and claim information and links to roofing product sources.

- Asbestos cement roofing shingles, now replaced with fiber cement roof shingles are similar to slate in durability and costs - see slate roofing below.

- Asphalt roofing shingles have an installed cost (including labor) of $100 - $350 per square. (one square covers 100 sq .ft. of roof surface) Asphalt shingles have a typical life expectancy of 15-25 years, with some warranties extending up to 45 years, and asphalt roof shingles typically weigh 225-385 pounds per square.

- Clay tile roofing material and installation labor are more expensive than alternate materials, but the material has a life expectancy of up to 350 years where high quality vitreous tiles are used. Clay tiles are heavy, weighing between 850 and 1,700 pounds per square.

- Wood roofing shingles material cost $150-200 per square, with an installed cost of $130 - $160 / square. Wood shingle roofs have a typical life expectancy of 10-40 years, and weigh 300-400 pounds per square.

- Metal roofing material costs $35 - 250 per square (wide range because of wide range of types of metal roofing), with an installed cost of $35 - $400 / square, a life of 15-40 years or more (a roof kept properly coated can last longer), and weigh 50 - 270 pounds / square. A high end aluminum metal roof may cost $800 - $1000 / square.

- Thatch roofing - typical life 15-25 years. Cost varies by geographic locale, roof pitch, materials.

- Slate roofing has an installed cost of $900 - $1,000 per square, has a life expectancy of 30 - 100 years (or 300 or more in some cases), and weighs 500-1,000 pounds/square. Synthetic slates cost less, typically $700 -$900 per square.

- Membrane roofing such as modified bitumen, rubber, or built up roofing using tar and gravel have a life expectancy of 20 - 40 years, varying significantly depending on materials and workmanship, and may cost $750 to $1000 per square.

Below at left are several thatch roofed structures on the Pacific Coast of Mexico and at below right, contrasting with the 1976 beer-drinking festival hosted by the author and Steve Coursey below the thatch roof photo at page top, the author enjoys coffee below a thatched roof in La Manzanilla, Mexico in 2011.

...

Reader Comments, Questions & Answers About The Article Above

Below you will find questions and answers previously posted on this page at its page bottom reader comment box.

Reader Q&A - also see RECOMMENDED ARTICLES & FAQs

On 2017-12-07 by milo mccowan

Has anyone sprayed their palapas with linseed oil to extend the life?

On 2015-09-01 - by (mod) -

Deborah

NO kidding.

In my experience in Mexico roof thatching materials are usually obtained quite locally. The exact material varies among grasses, bamboo, rushes, or even sod, depending on where you live. I'd ask some local contractors or homeowners where they got theirs.

Ask for azotea de la paja

On 2015-08-29 by Deborah Dupré

Would you please tell me where can I buy Mexican thatching and bamboo products in Mexico? I live in Mexico and do not want to have to buy exported Mex. materials to the US and then have to import them back. Thank you.

On 2015-07-22 - by (mod) -

Thanks for the question, Nate. We're in central Mexico ourselves where palapas are typically made of palm or tall grasses.

If the existing roof framing is strong enough to carry the added weight, and if you are re-doing the entire roof and want a modern leak and SSSMT proof roof that looks like a traditional palapa you could install 1/2" plywood (or if necessary beef up the framing) over which for a perfect job I'd install a membrane (preferably ice and water shield but even heavy plastic might work) over which you can install a new palapa of sea grass.

The benefit of ice and water shield is that it will seal around any nails.

But at least here in Central Mexico I find that the climate is hot and dry enough that between even heavy rains the roof dries out enough that people get away with installing the roof covering (tiles or Tejas) right on the raw plywood. As long as the bottom edge of the plywood can drain to daylight even that rough approach works pretty well.

Perhaps in Yucatan where your climate is far more humid your rot worry is a real one. So ...

If you are going to give up on the palapa roof you can install corrugated fiberglass where you want light along with corrugated steel where you want shade, directly over framing without a plywood decking. The corrugated roofing is about as light as the palapa that it is replacing.

Thanks for introducing the term SSSMT's (spiders, snakes, scorpions, mosquitos, and ticks) - we get an occasional visit but mostly from scorpios and mosquitos.

If you can send me some photos of the existing roof from outside and inside and of the structure from outside (to get perspective) I'd appreciate it and may be able to offer further comment. Use the email at our page bottom CONTACT link.

On 2015-07-22 by Nate C

Hi, I have a small house in the Yucatan with a palapa (sea grass) roof. The roof is aging and I am looking at replacement at some point.

I now have the inside lined with mosquito screen to try to keep the pests out, of which there are many

. I call them SSSMT's (spiders, snakes, scorpions, mosquitos, and ticks). I'm thinking of going to a solid panel roof of some type that I could truly caulk and seal to try and keep the jungle out. Ideally I'd like to use the framing that is there now.

Any suggestions? I would think about plywood with shingle or something over but I'm a little concerned about plywood rotting in that environment. Concrete panels? Fiberglass?

Thanks for any suggestions!! Nate

Question:

8 June 2015 Kevin Riley said:

Nice summary of the archeology of thatch roofs. Please include a bit more on modern thatch replacement with PVC or other man-made materials.

Reply:

Thanks for the suggestion, Kevin, we'll work on it. Indeed I've seen some remarkable plastic thatch products made in China - and am a bit nervous about the product.

...

Continue reading at FIRE RATINGS for ROOF SURFACES or select a topic from the closely-related articles below, or see the complete ARTICLE INDEX.

Or see these

Recommended Articles

ROOFING INSPECTION & REPAIR - home

Suggested citation for this web page

THATCH ROOFING at InspectApedia.com - online encyclopedia of building & environmental inspection, testing, diagnosis, repair, & problem prevention advice.

Or see this

INDEX to RELATED ARTICLES: ARTICLE INDEX to BUILDING ROOFING

Or use the SEARCH BOX found below to Ask a Question or Search InspectApedia

Ask a Question or Search InspectApedia

Try the search box just below, or if you prefer, post a question or comment in the Comments box below and we will respond promptly.

Search the InspectApedia website

Note: appearance of your Comment below may be delayed: if your comment contains an image, photograph, web link, or text that looks to the software as if it might be a web link, your posting will appear after it has been approved by a moderator. Apologies for the delay.

Only one image can be added per comment but you can post as many comments, and therefore images, as you like.

You will not receive a notification when a response to your question has been posted.

Please bookmark this page to make it easy for you to check back for our response.

IF above you see "Comment Form is loading comments..." then COMMENT BOX - countable.ca / bawkbox.com IS NOT WORKING.

In any case you are welcome to send an email directly to us at InspectApedia.com at editor@inspectApedia.com

We'll reply to you directly. Please help us help you by noting, in your email, the URL of the InspectApedia page where you wanted to comment.

Citations & References

In addition to any citations in the article above, a full list is available on request.

- Green Roof Plants: A Resource and Planting Guide, Edmund C. Snodgrass, Lucie L. Snodgrass, Timber Press, Incorporated, 2006, ISBN-10: 0881927872, ISBN-13: 978-0881927870. The text covers moisture needs, heat tolerance, hardiness, bloom color, foliage characteristics, and height of 350 species and cultivars.

- Green Roof Construction and Maintenance, Kelley Luckett, McGraw-Hill Professional, 2009, ISBN-10: 007160880X, ISBN-13: 978-0071608800, quoting: Key questions to ask at each stage of the green building process Tested tips and techniques for successful structural design Construction methods for new and existing buildings Information on insulation, drainage, detailing, irrigation, and plant selection Details on optimal soil formulation Illustrations featuring various stages of construction Best practices for green roof maintenance A survey of environmental benefits, including evapo-transpiration, storm-water management, habitat restoration, and improvement of air quality Tips on the LEED design and certification process Considerations for assessing return on investment Color photographs of successfully installed green roofs Useful checklists, tables, and charts

- Handbook of Building Crafts in Conservation, Jack Bower, Ed., Van Nostrand Reinhold Company, NY 1981 ISBN 0-442-2135-3 Library of Congress Catalog Card Nr. 81-50643.

- Historic Preservation Technology: A Primer, Robert A. Young, Wiley (March 21, 2008) ISBN-10: 0471788368 ISBN-13: 978-0471788362

- In addition to citations & references found in this article, see the research citations given at the end of the related articles found at our suggested

CONTINUE READING or RECOMMENDED ARTICLES.

- Carson, Dunlop & Associates Ltd., 120 Carlton Street Suite 407, Toronto ON M5A 4K2. Tel: (416) 964-9415 1-800-268-7070 Email: info@carsondunlop.com. Alan Carson is a past president of ASHI, the American Society of Home Inspectors.

Thanks to Alan Carson and Bob Dunlop, for permission for InspectAPedia to use text excerpts from The HOME REFERENCE BOOK - the Encyclopedia of Homes and to use illustrations from The ILLUSTRATED HOME .

Carson Dunlop Associates provides extensive home inspection education and report writing material. In gratitude we provide links to tsome Carson Dunlop Associates products and services.